BEING CLOSE (2019), installation view, Aidron Duckworth Art Museum, Meriden NH

BEING CLOSE (2019), detail of the wheel. Pigmented cement board and steel truss connected to a tree for lateral stability. Turning this wheel sents the book into the field.

BEING CLOSE (2019) detail of the truss. Spanning fifty linear feet, an equilateral truss (measures nine inches and comes apart in five 10’ sections) with a gear on either end, supports a length of chain to move a book. Three pairs of legs support the truss. .

BEING CLOSE (2019), detail of the book.

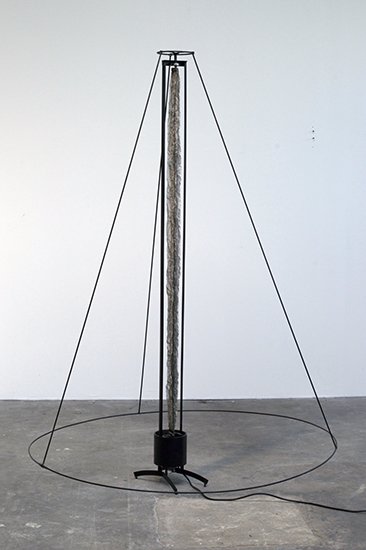

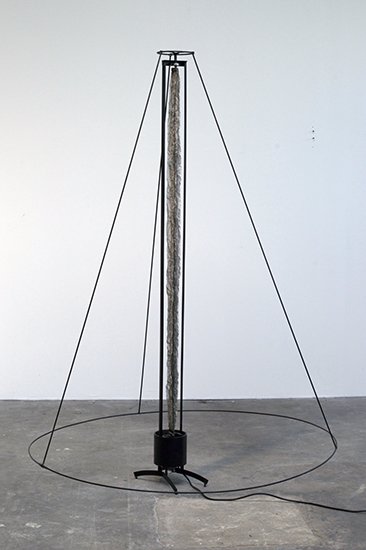

Host (2018), steel with motor, backer rod, foot pedal and timer, freestanding kinetic sculpture: 15 feet tall, variable 6 foot diameter pile unspools at base

Host (2018), detail, one of six backer rod spools, steel with motor, foot pedal and timer, freestanding kinetic sculpture: 15 feet tall, variable 6 foot diameter pile unspools at base

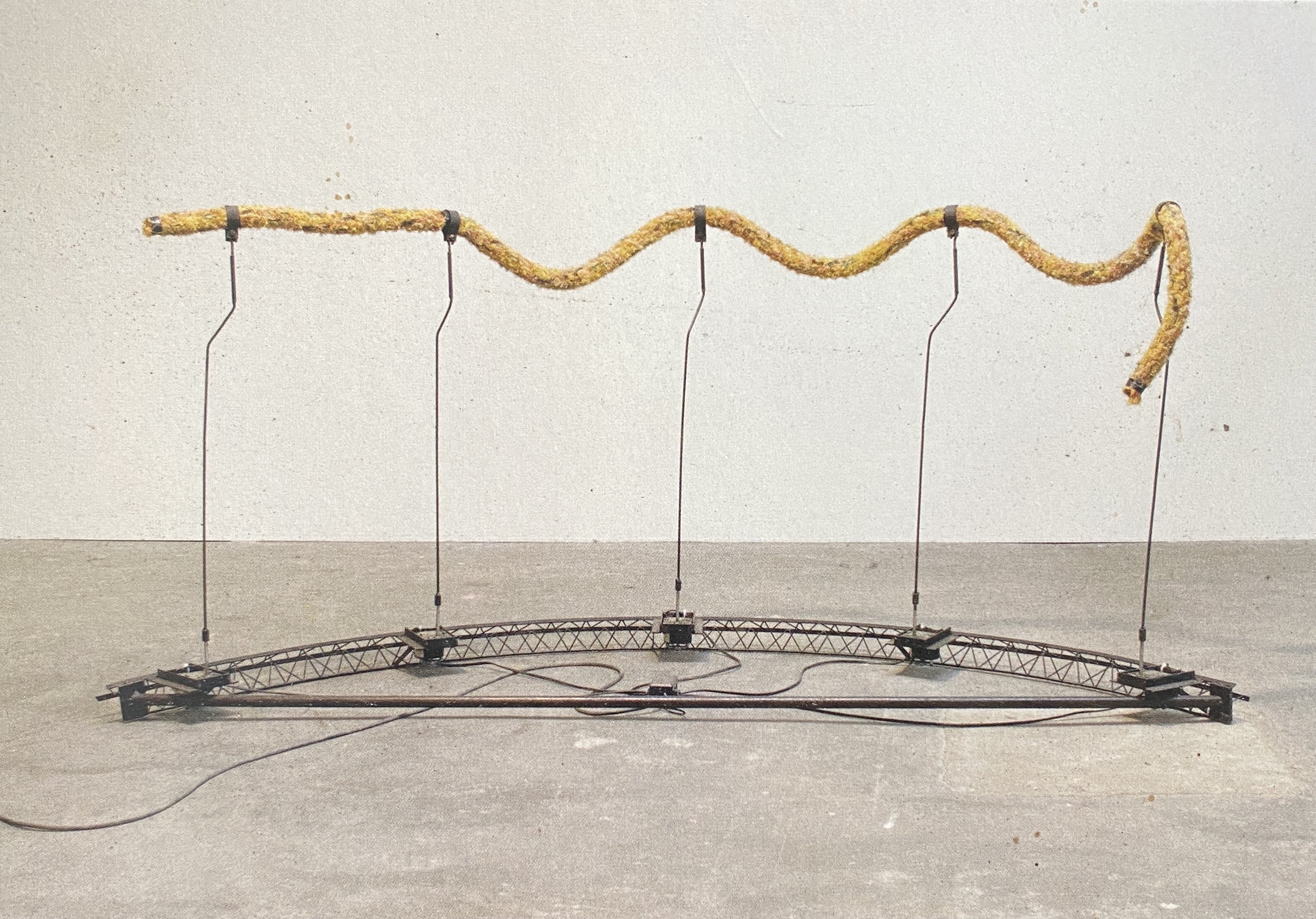

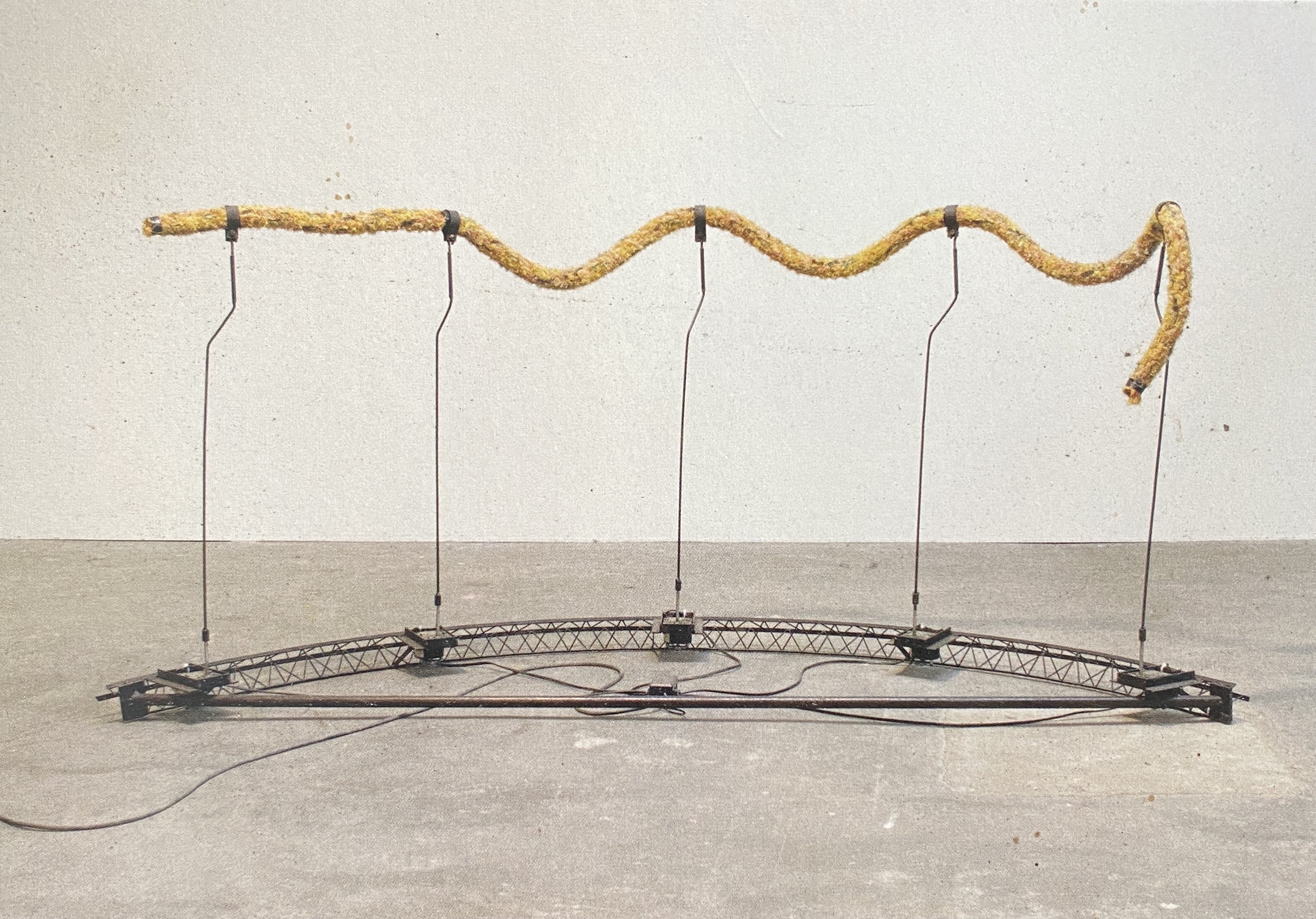

Rope Trick (2016), 78” l x 28”w x 36”h, steel with motor, hauzer, foot pedal and timer, freestanding kinetic sculpture

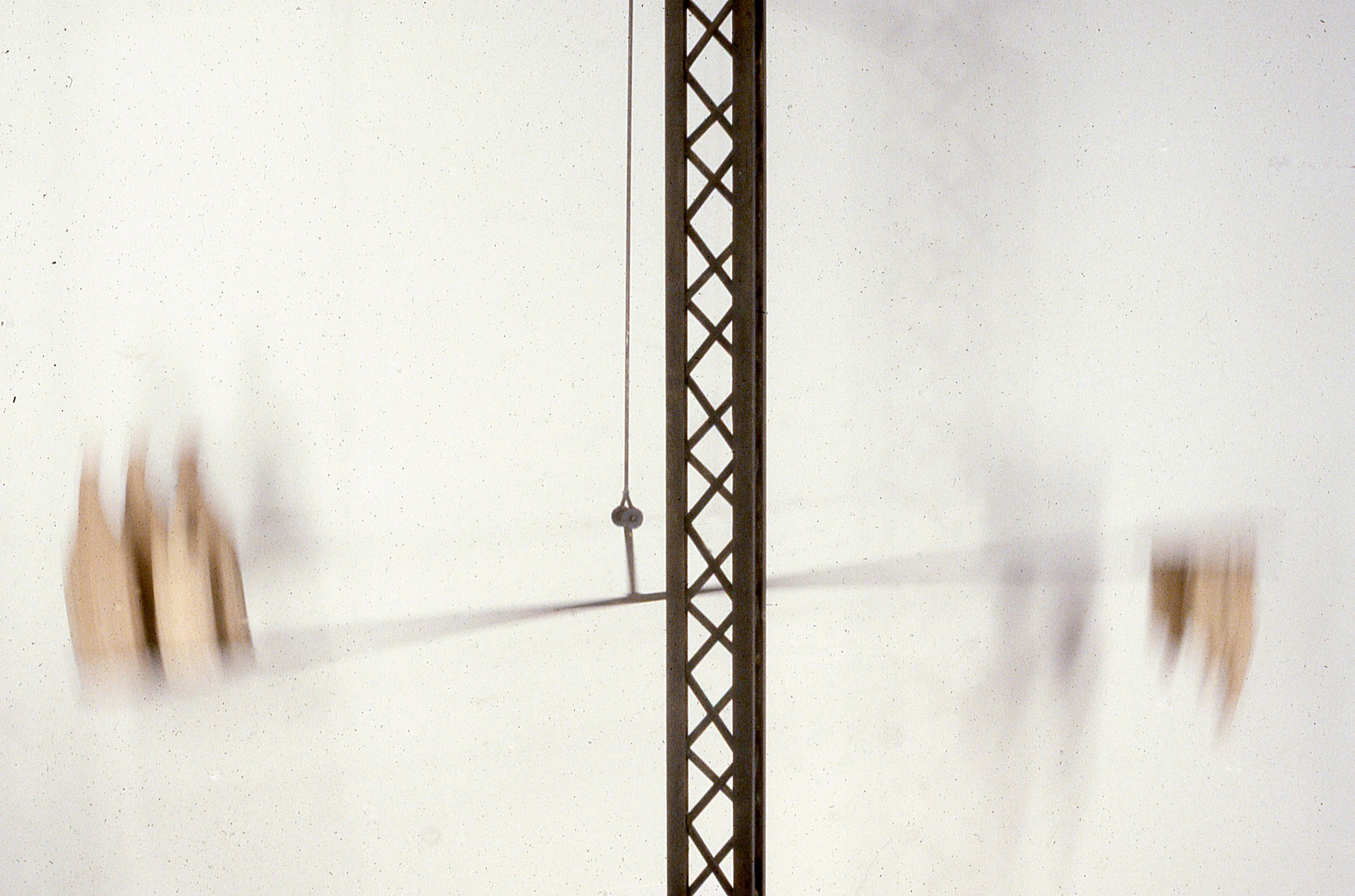

Working (2016), string, gloves and steel, foot pedal motor and timer, freestanding sculpture: 54 inches high, spinning 30” radius

Dervish (2016), stainless mesh and steel, foot pedal and motor, freestanding sculpture: height 7 foot 6 inches, 5 foot diameter

Watching (2014), 24’l 12’w x 12’h, steel with motor, vinyl, foot pedal and timer, freestanding kinetic sculpture

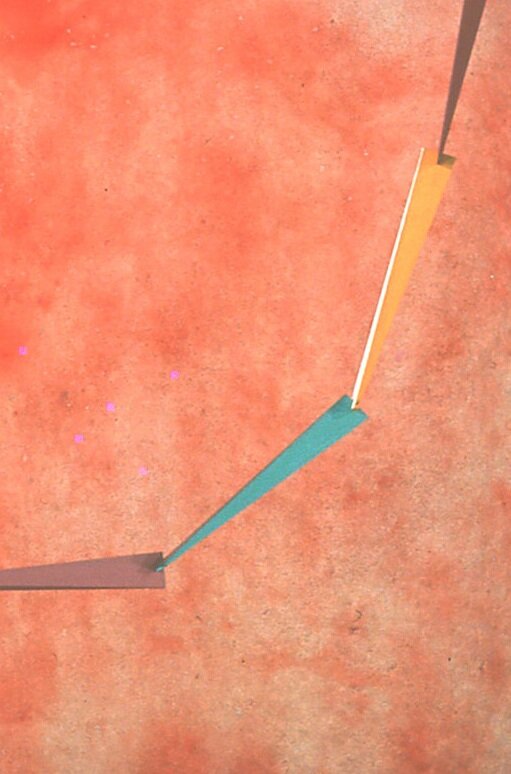

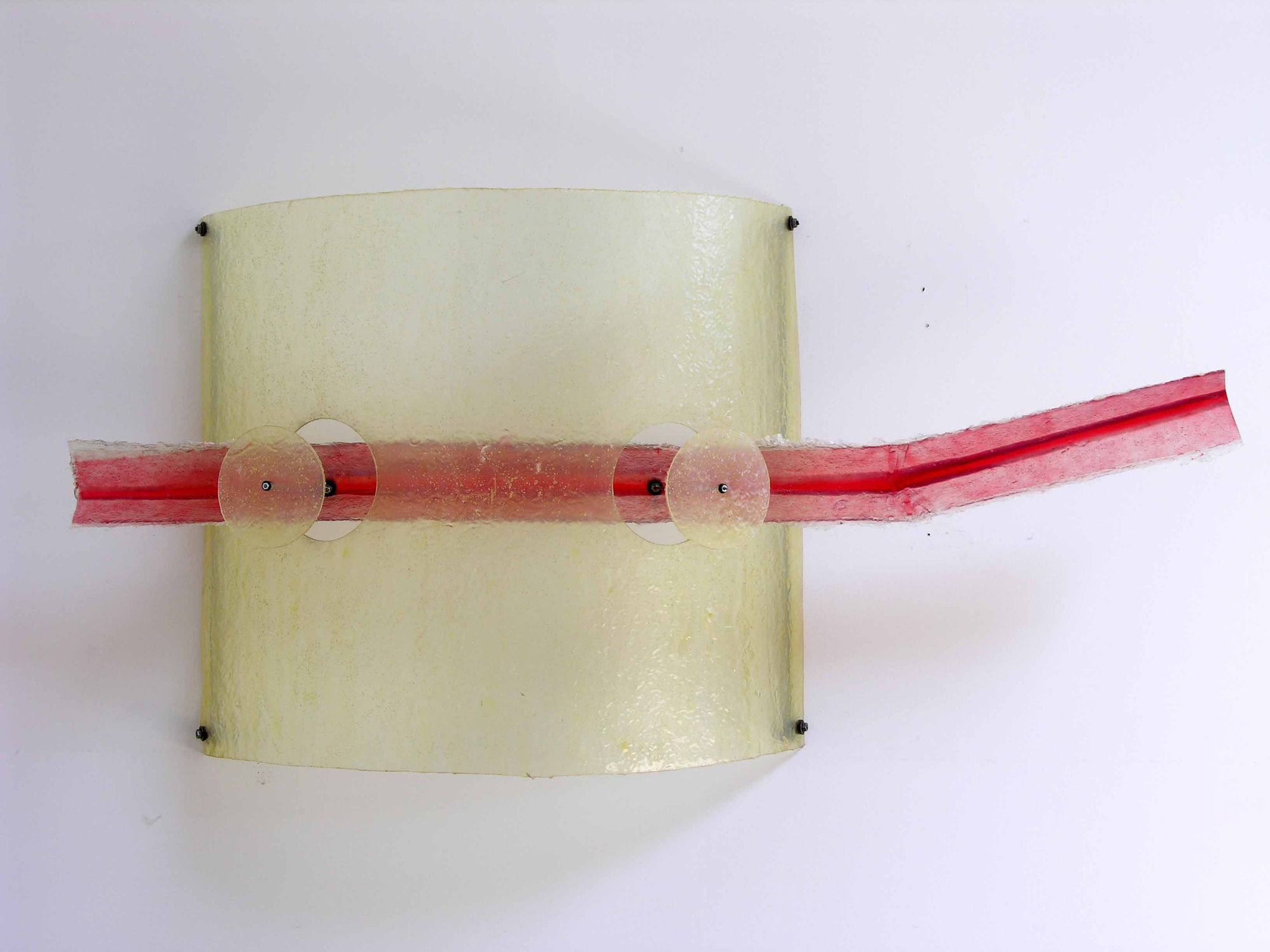

Set (2014), synthetic polymer resin, pigment, c clamps and steel, 40 x 80 x 160 inches (1 x 1.5 x 4 m)

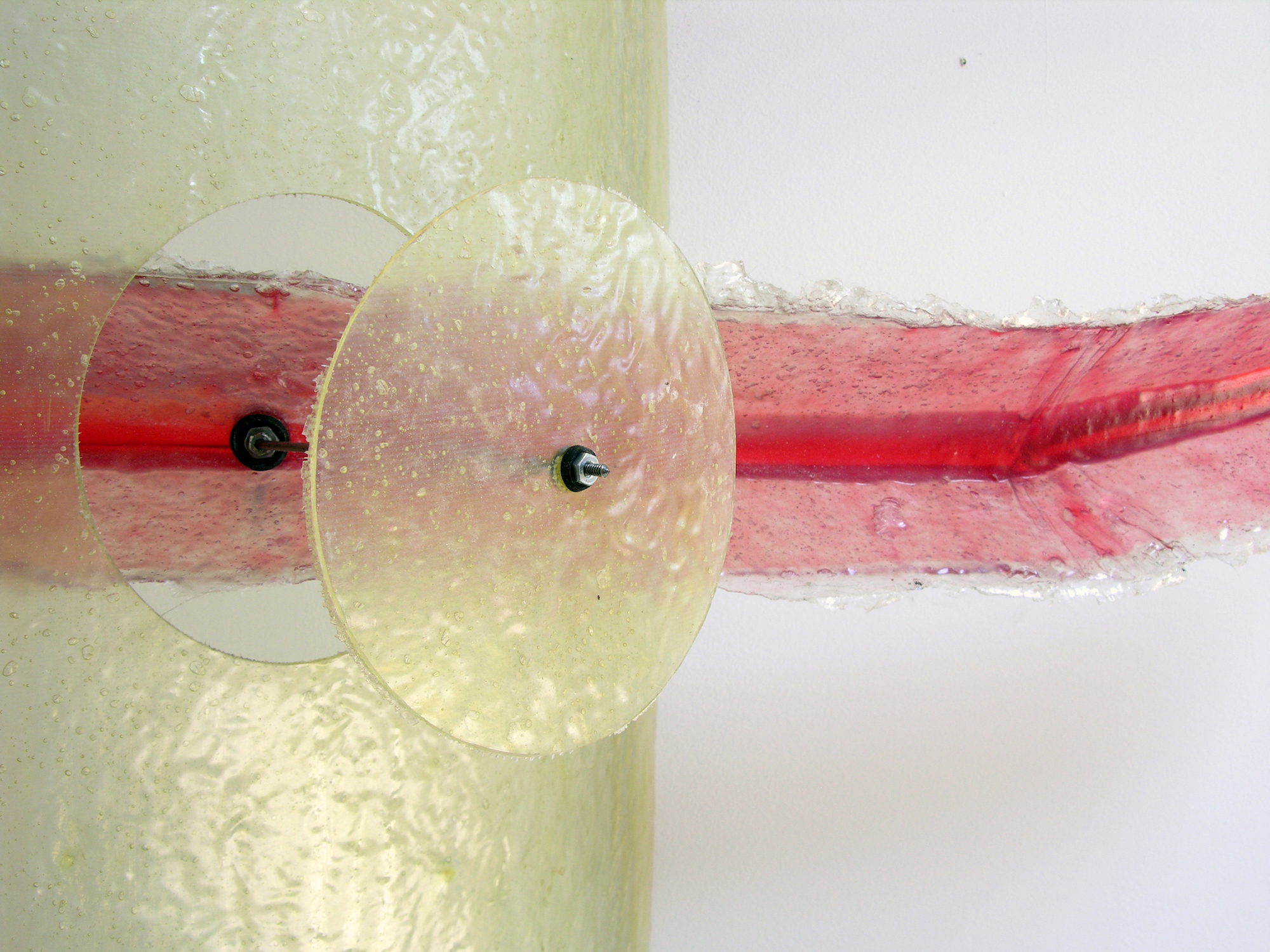

Set (2014), detail of two discs grazing the floor, pigmented resin, c clamps and steel, 40 x 80 x 160 inches (1 x 1.5 x 4 m)

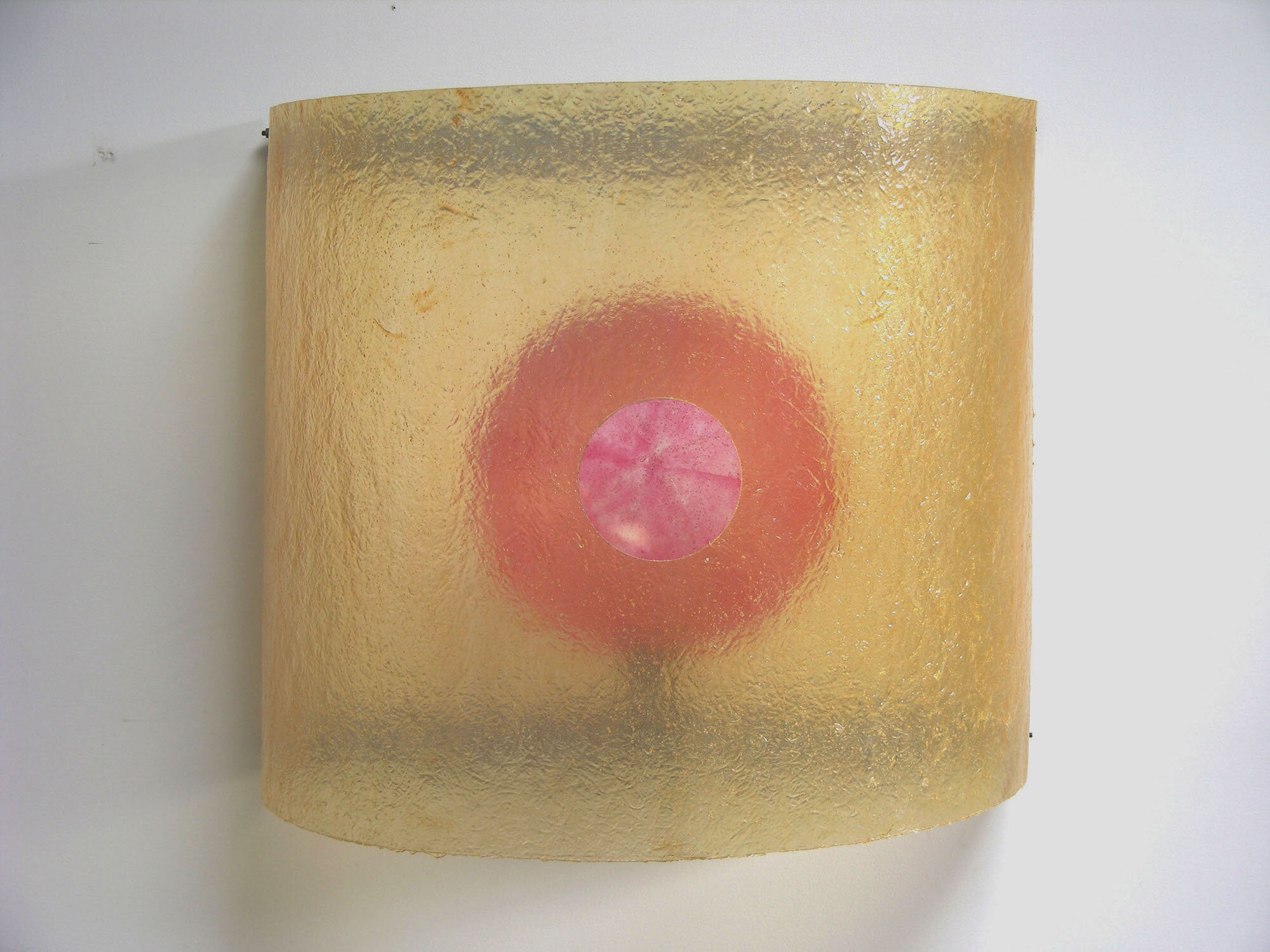

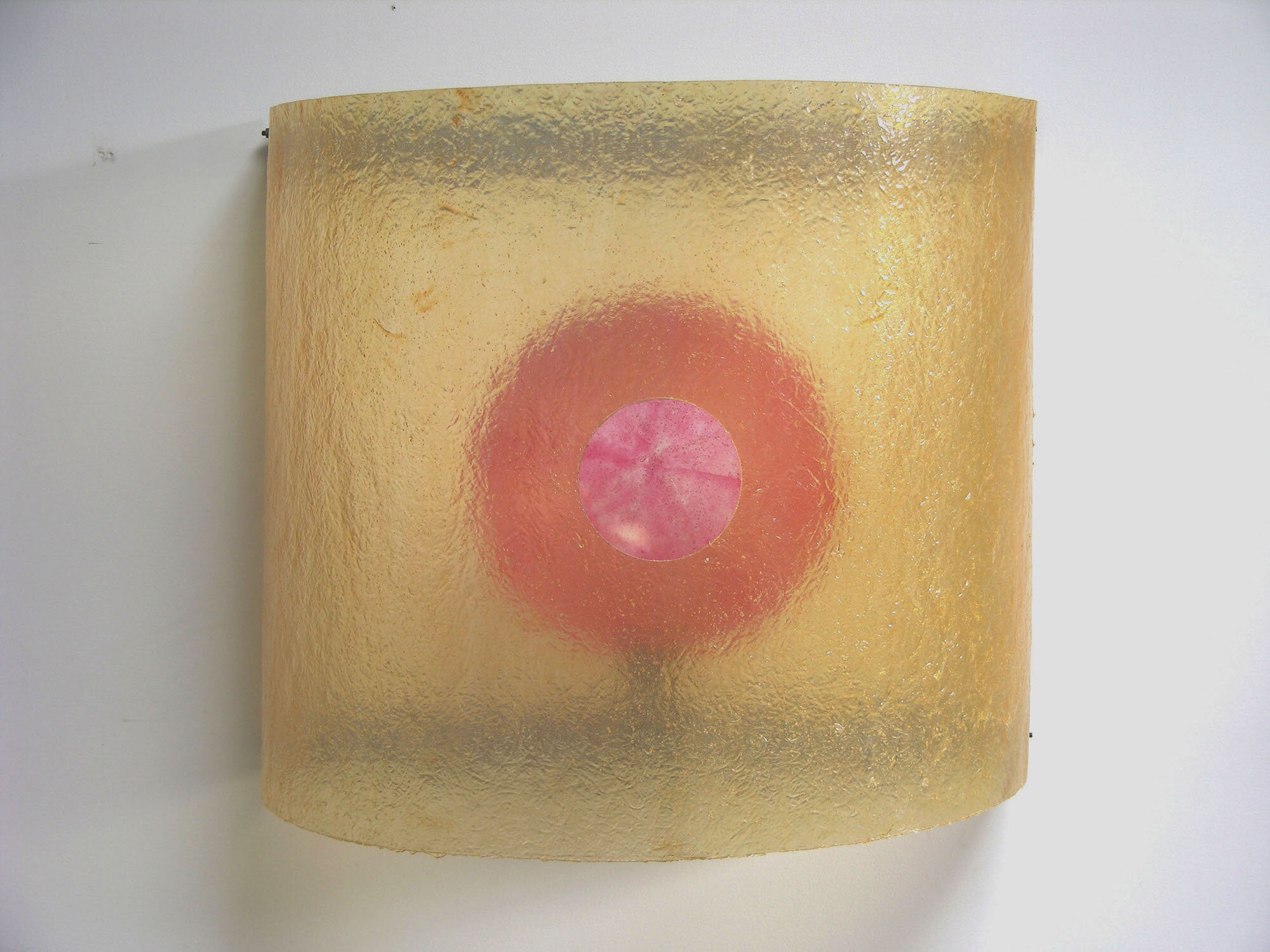

Lampshade (2000), resin, pigment, steel, concrete and boots

Lampshade (2000), detail - second form suspended within, pigmented resin, steel, concrete and boots

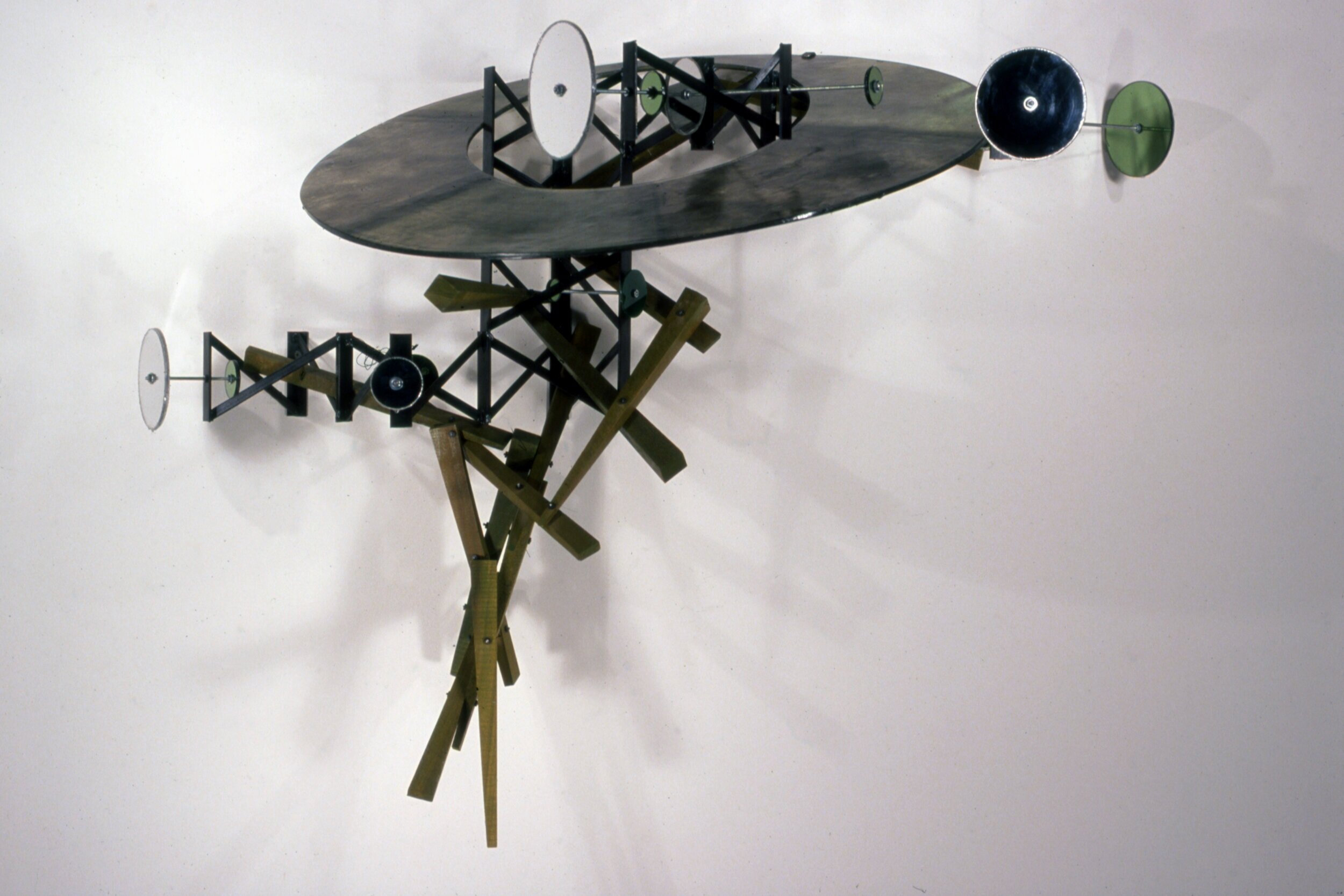

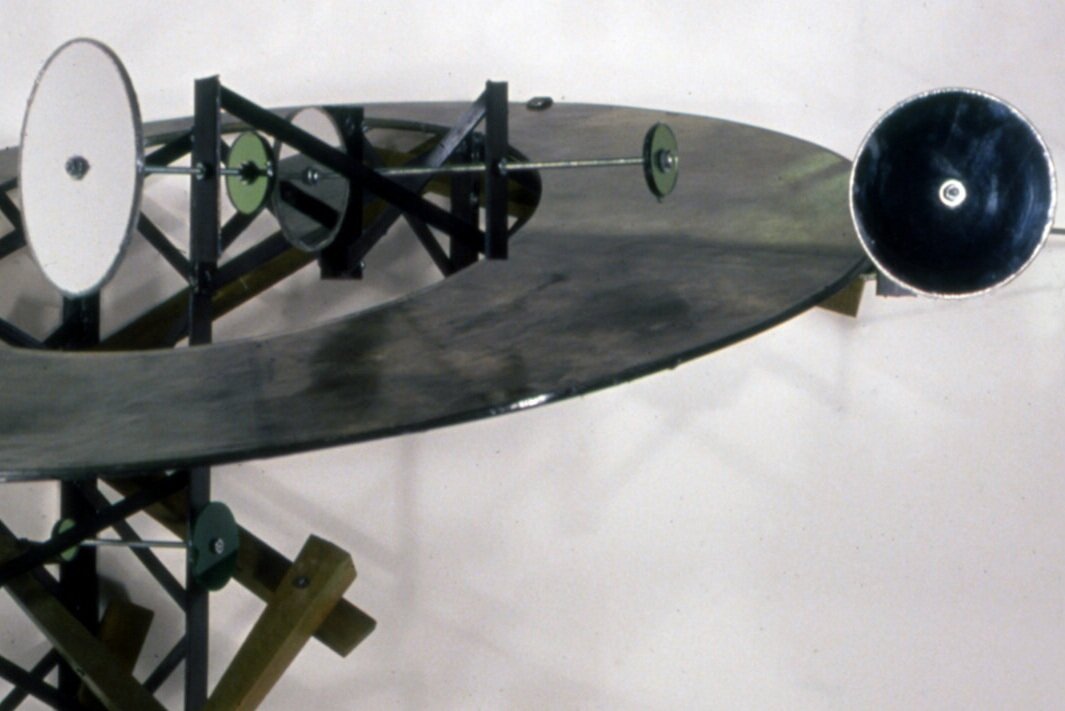

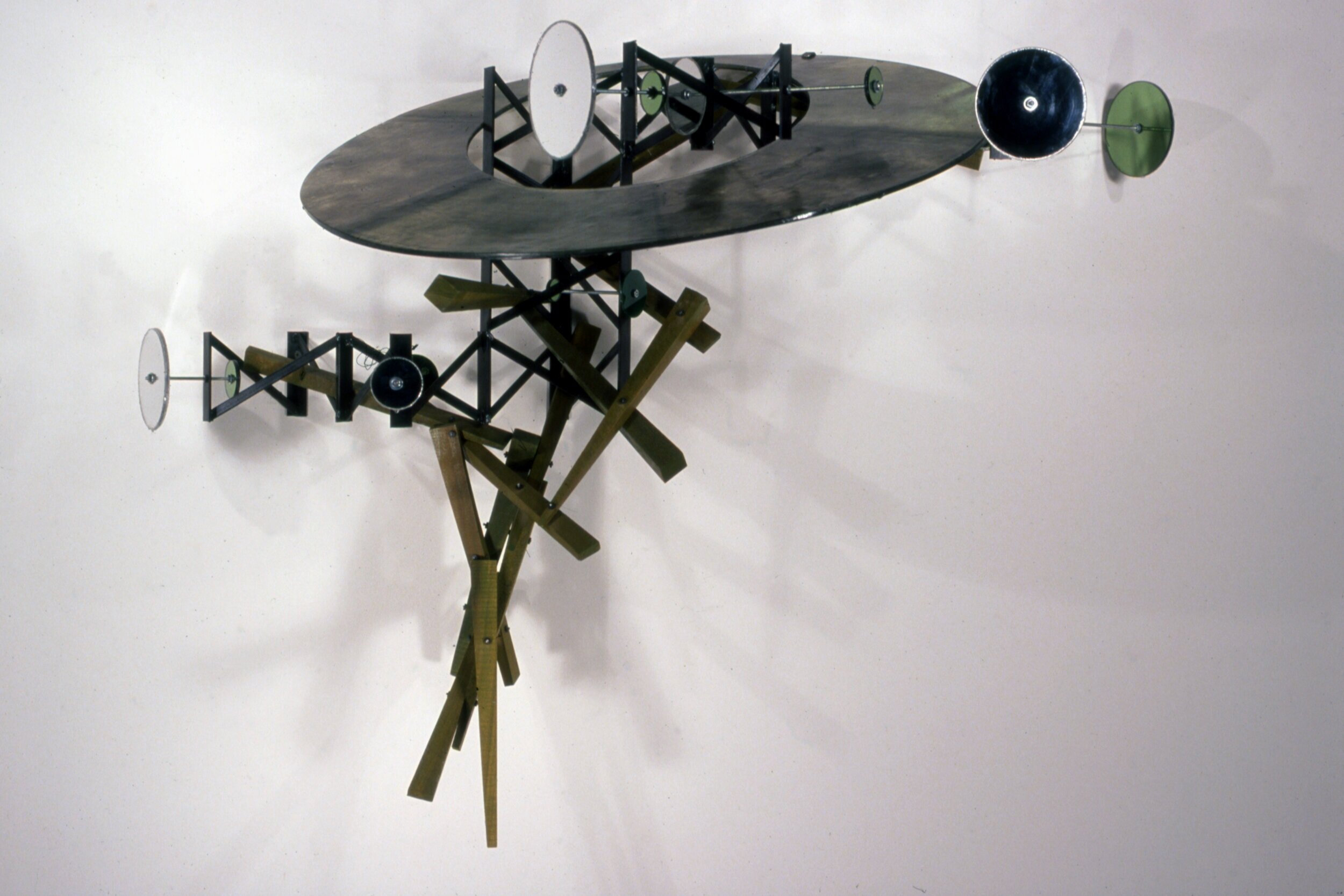

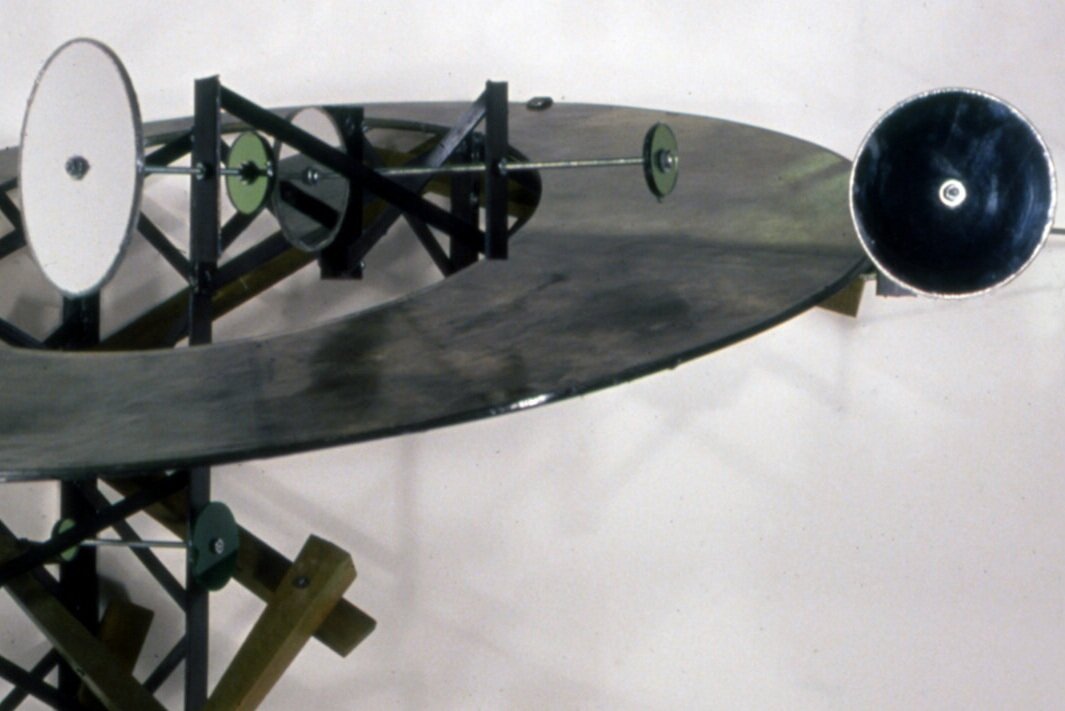

S Machine (2007), tutu fabric, steel, wood

A few feet away, “S. Machine,” another hollow steel truss, flirts with other modalities. It is lightly stuffed with a pink gauzy material evoking the feminine; dangling one third of the way from the top are wooden orbs suggestive of buoys, flotation devices, or (again) breasts. Although not literally kinetic, the piece has movement: the frothy synthetic fabric seems both to spill out of and be trapped by the girded column. The effect is one of abiding dichotomies—linear and curved, steely and gossamer, “masculine” and “feminine”—that defy resolution.

S Machine (2007), detail of the materials in use: pink tutu fabric stuffed into the steel with carved poplar painted white

The show rewards viewing from different angles—close scrutiny of the pieces’ materials and nuances of movement—and a consideration of the pieces in relation to each other. Ultimately, one notices that Butter’s works create provisional scenarios and spaces—scenes one might hope to enter and explore—and moments of rest. They alternately invite and disrupt a sense of ease and stability—pulling the viewer in only to stymy expectations that become apparent by being thwarted. Viewed together, Butter’s sculptures and paintings embody a dialogue about the tensions between stillness and movement, 2-D and 3-D, with each piece contributing a motive energy of its own. The invitation to participate proves difficult to resist—upon leaving the show, this viewer realized that she had served as a willing and engaged foil in an ongoing exploration of disequilibrium. - Mara Dale, “Astir” Whitehot Magazine, December 2015

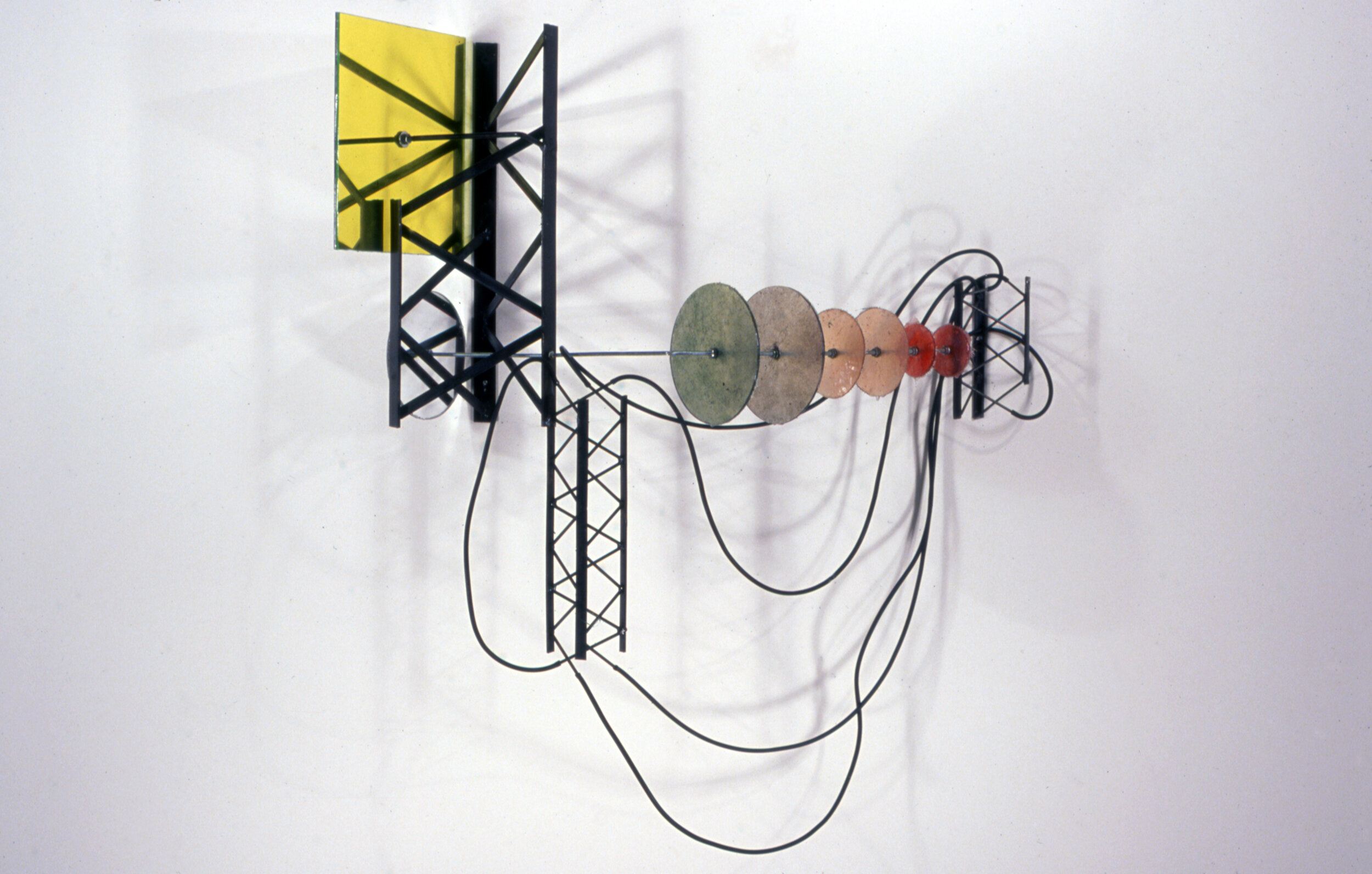

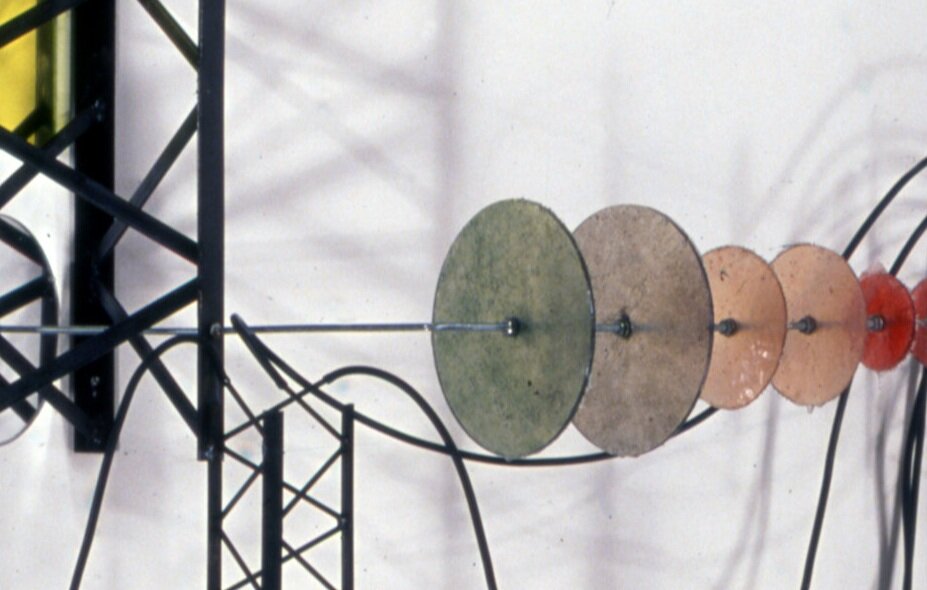

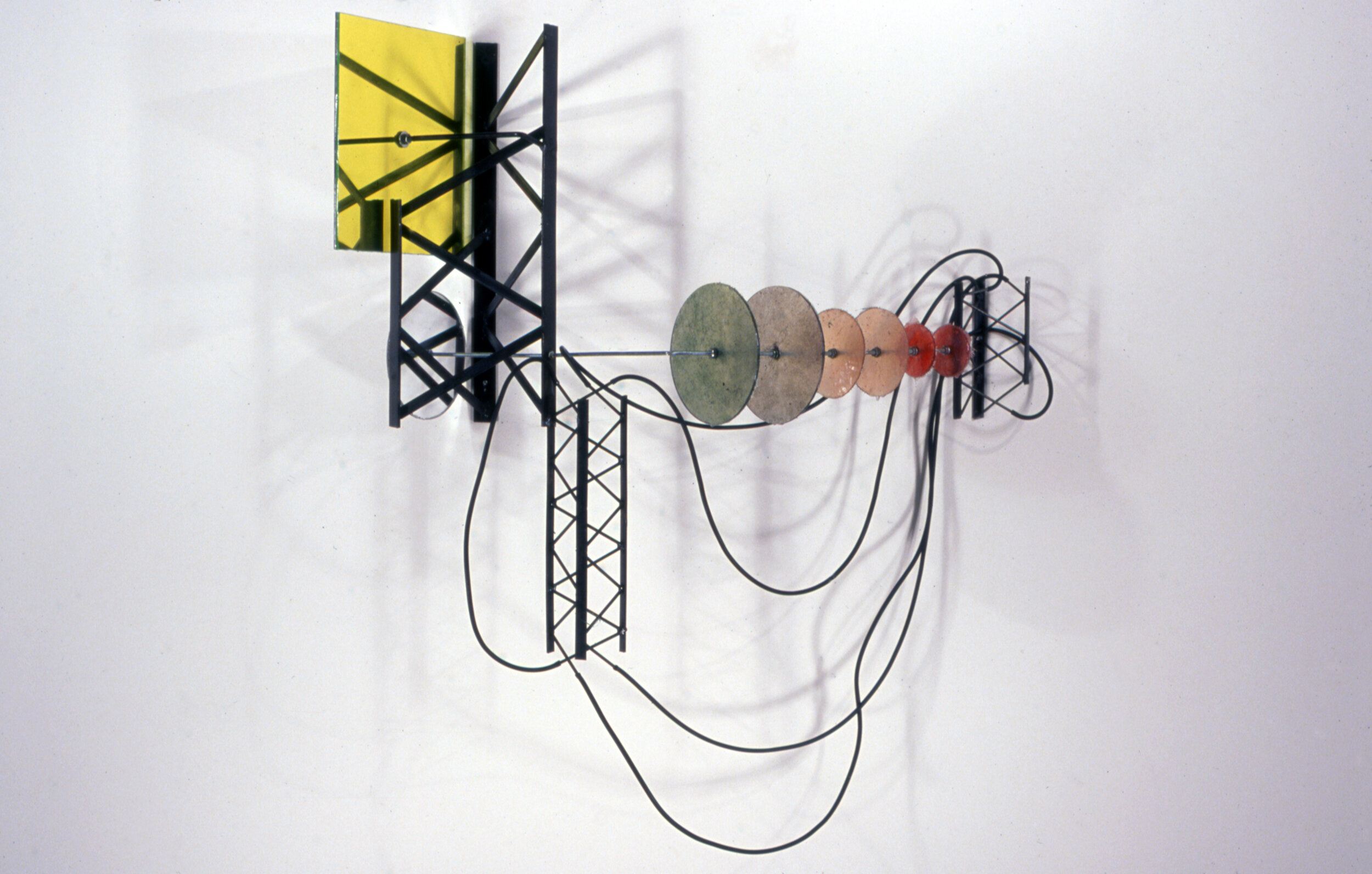

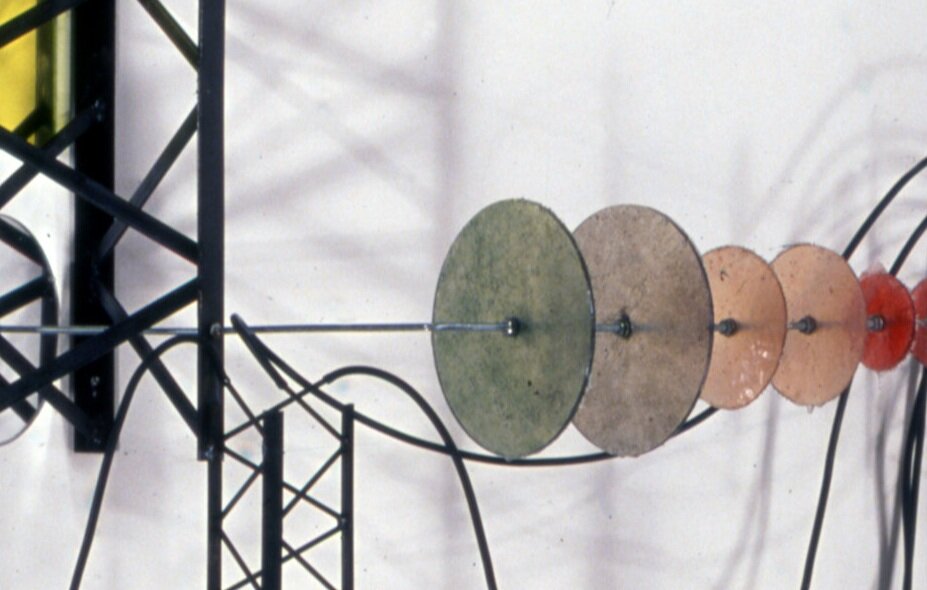

Strange Brew (2006), resin, pigment, steel, thread

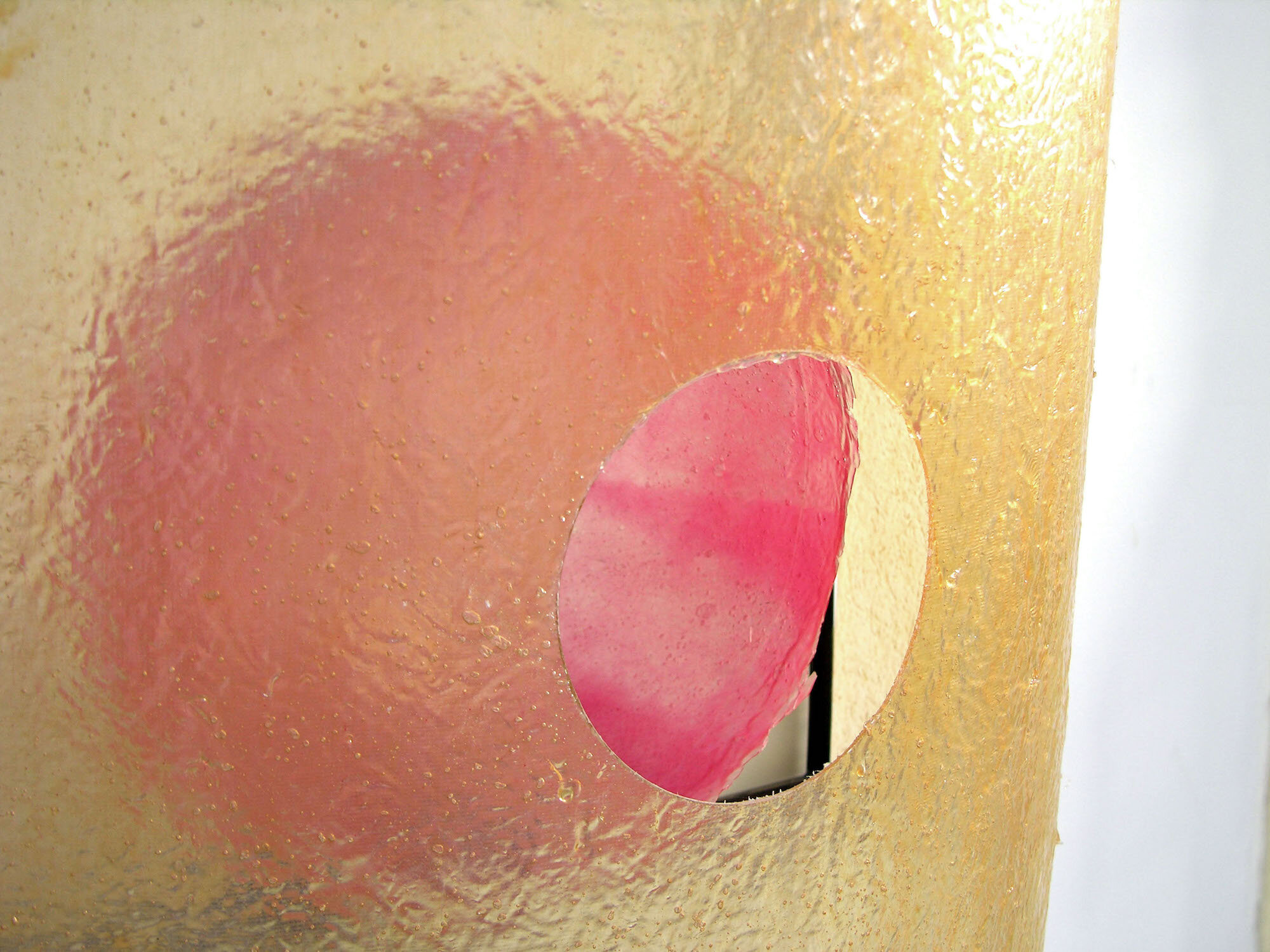

Strange Brew (2006), detail of the pivot point, pigmented resin, pigment, steel

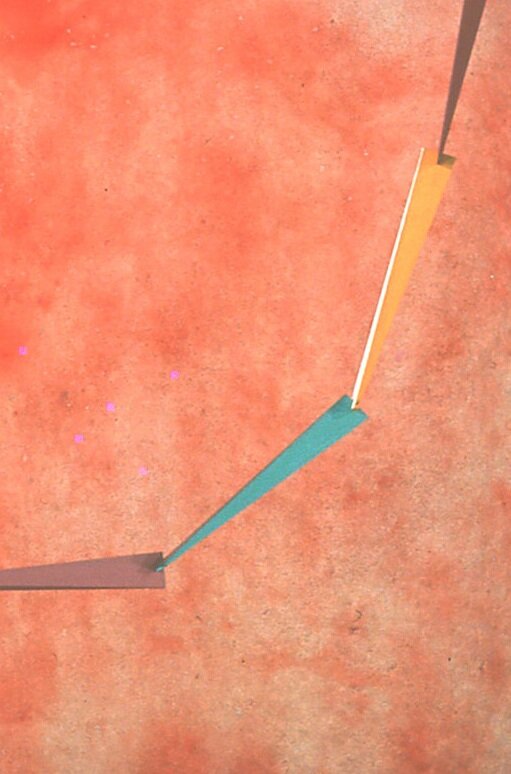

Levity (1998), synthetic polymer resin, pigment and wood

detail, Levity (1998), synthetic polymer resin, pigment and wood

Monk (2006), resin, pigment, steel

Procession, resin, pigment, wood, steel

detail, Procession (2000), resin, pigment, steel, wood

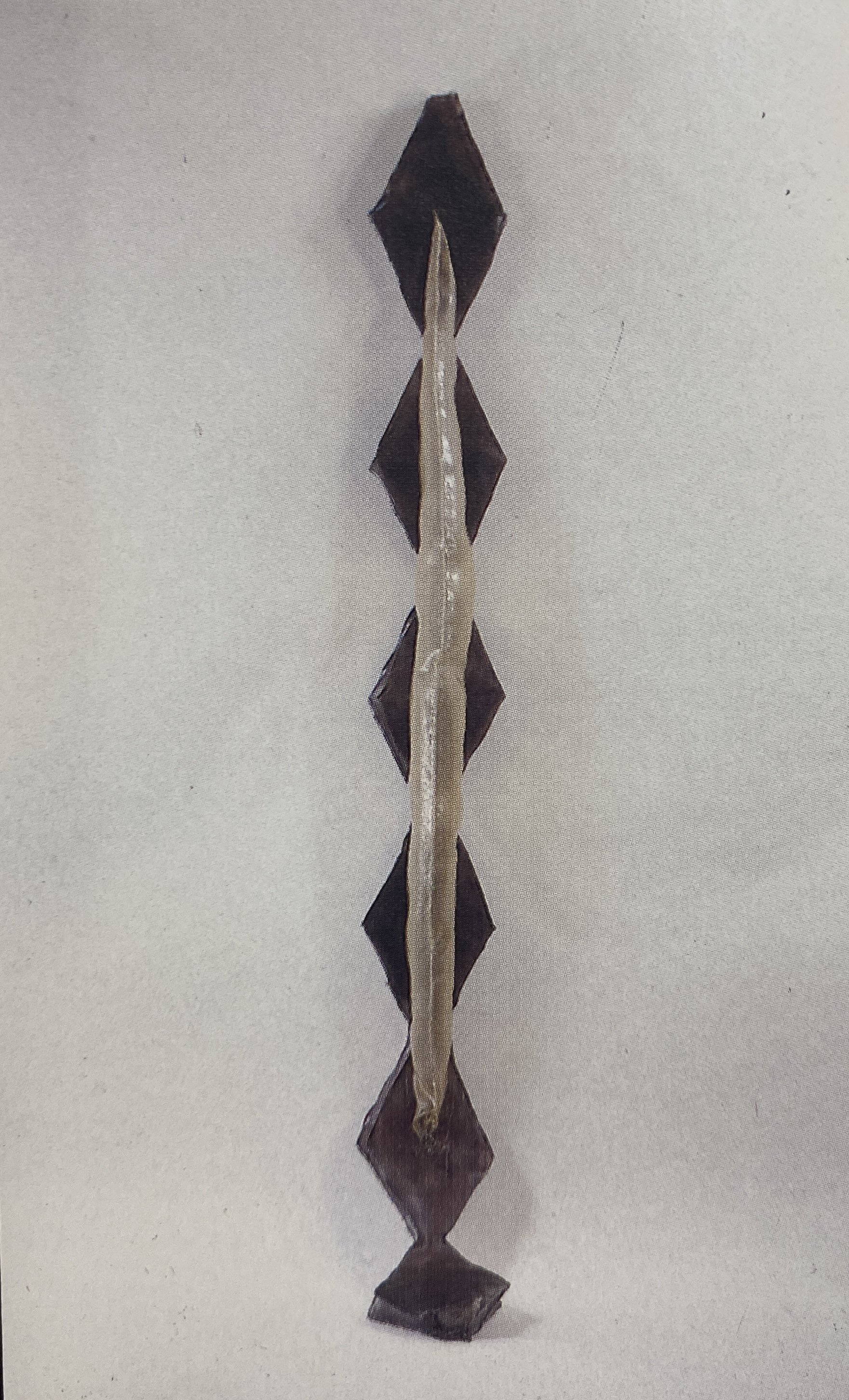

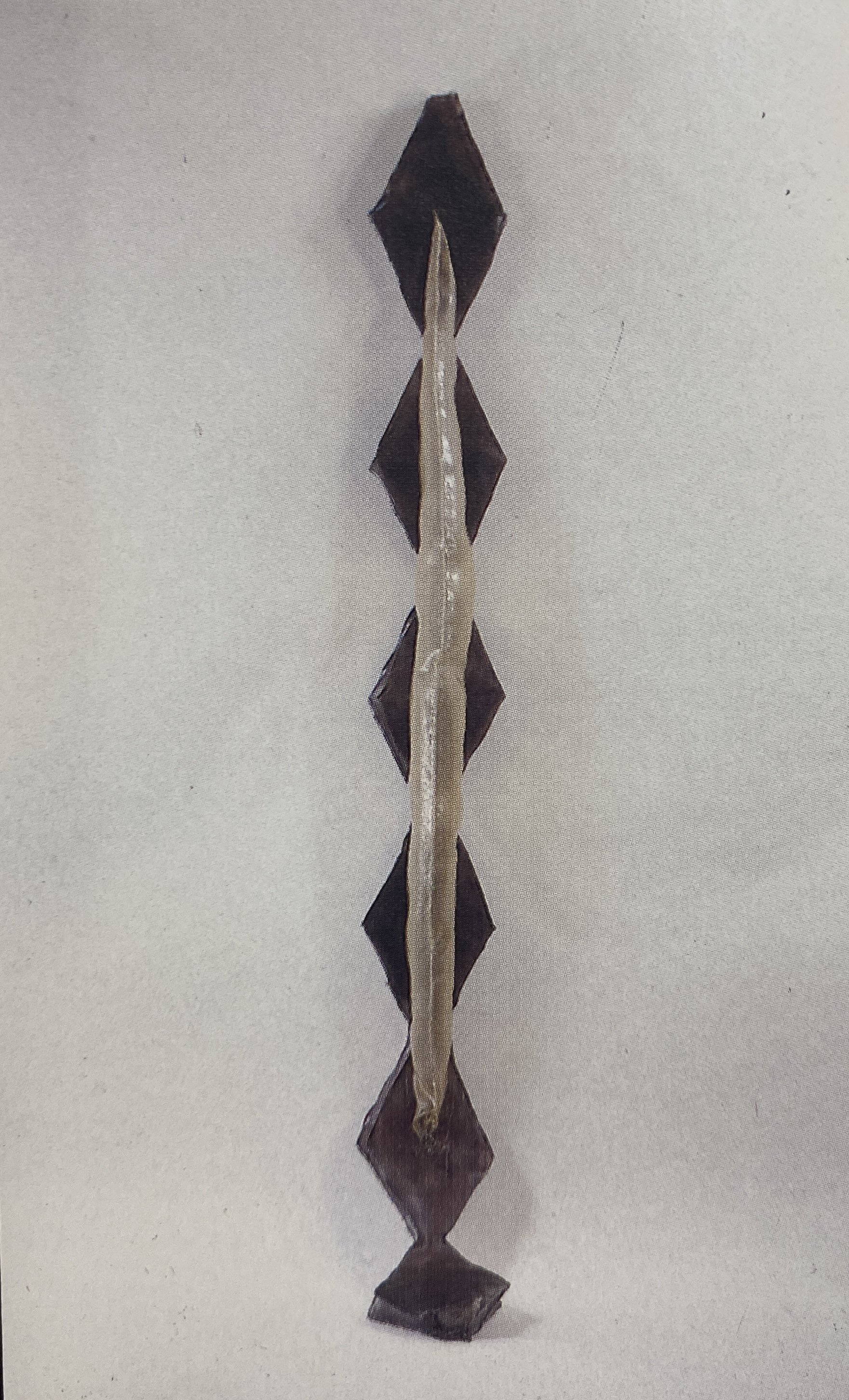

Necklace (2003), resin, pigment, wood, steel, 54 x 12 x 72 inches (1.3 x .3 x 1.8 m)

detail, Necklace (2003), resin, pigment, wood, steel, 54 x 12 x 72 inches (1.3 x .3 x 1.8 m)

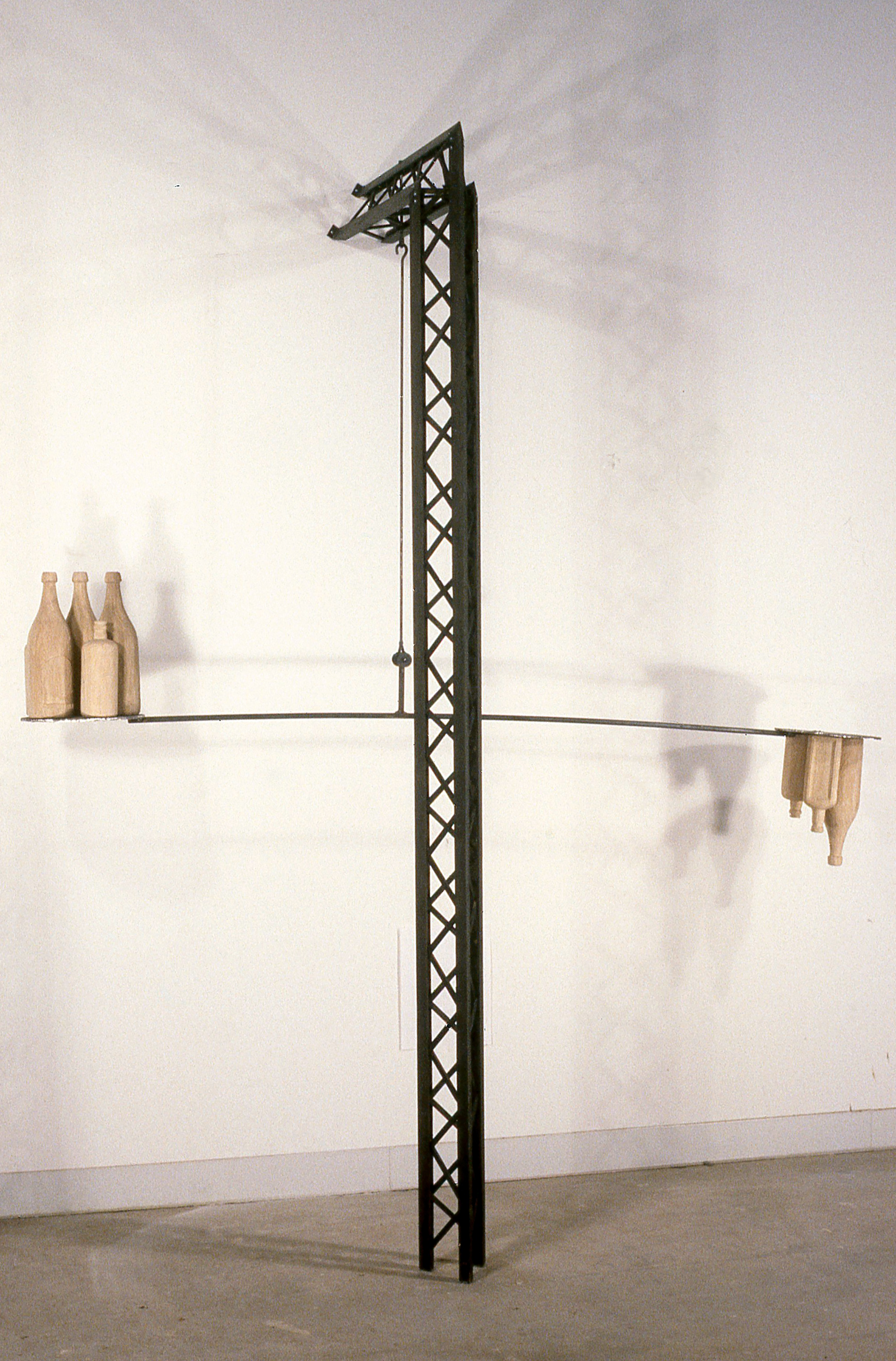

Drinking Drunk (2000), steel, wood

You must always be intoxicated. It is the key to all: the one question. In order not to feel the horrible burden of Time breaking your back and bending you toward the earth, you must become drunk, without truce. But on what? On wine, poetry or virtue, as you wish. Bur you must get drunk.

detail, Drinking Drunk (2000), steel, wood

And if at times, on the steps of a palace, on the green grass of a ditch, in the mournful solitude of your room, you awaken, and your intoxication is already diminished or gone, ask the wind, the wave, the star, the bird, the clock, everything that flees, everything that groans, everything that rolls, that sings, that speaks, ask what time it is: and the wind, the wave, the star, the bird, the clock will answer you: ‘it is time to get intoxicated! Become intoxicated! On wine, on poetry, or on virtue, as you will.’ -Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867), ‘On Intoxication’, Spleen of Paris, (ed. Dover: 1992)

Still Life (1999), steel, stone, wood, wire, resin

Mask (2007), resin, pigment, steel

detail, Mask (2007), resin, pigment, steel

Belly (2007), polyester resin, pigment, steel

detail, Belly (2007), polyester resin, pigment, steel

Stand Off (2000), polyester resin, pigment, steel

Barn (1996), polyester resin, pigment, steel, 56 x 59 x 24 inches (1.4 x 1.5 x .1 meters)

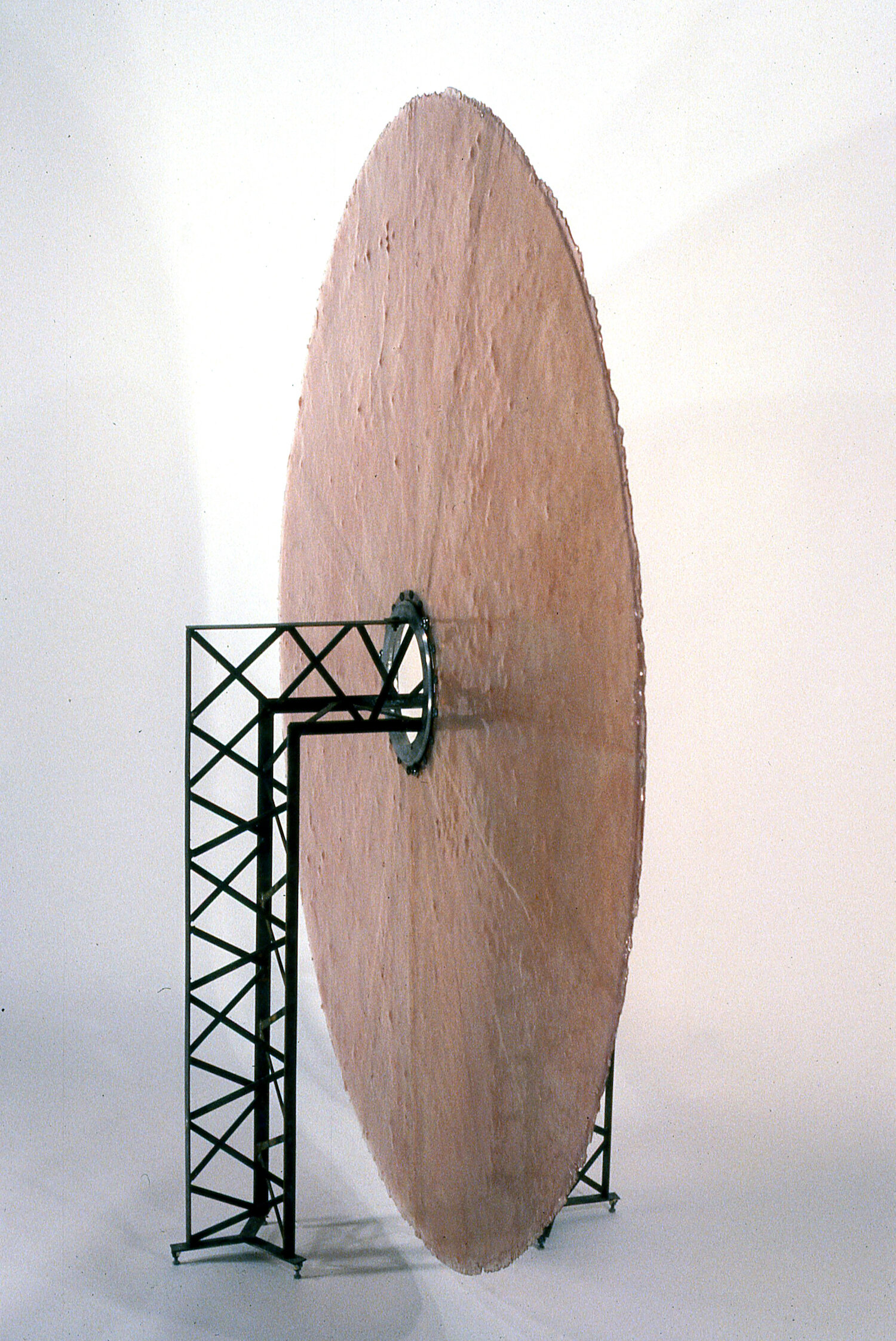

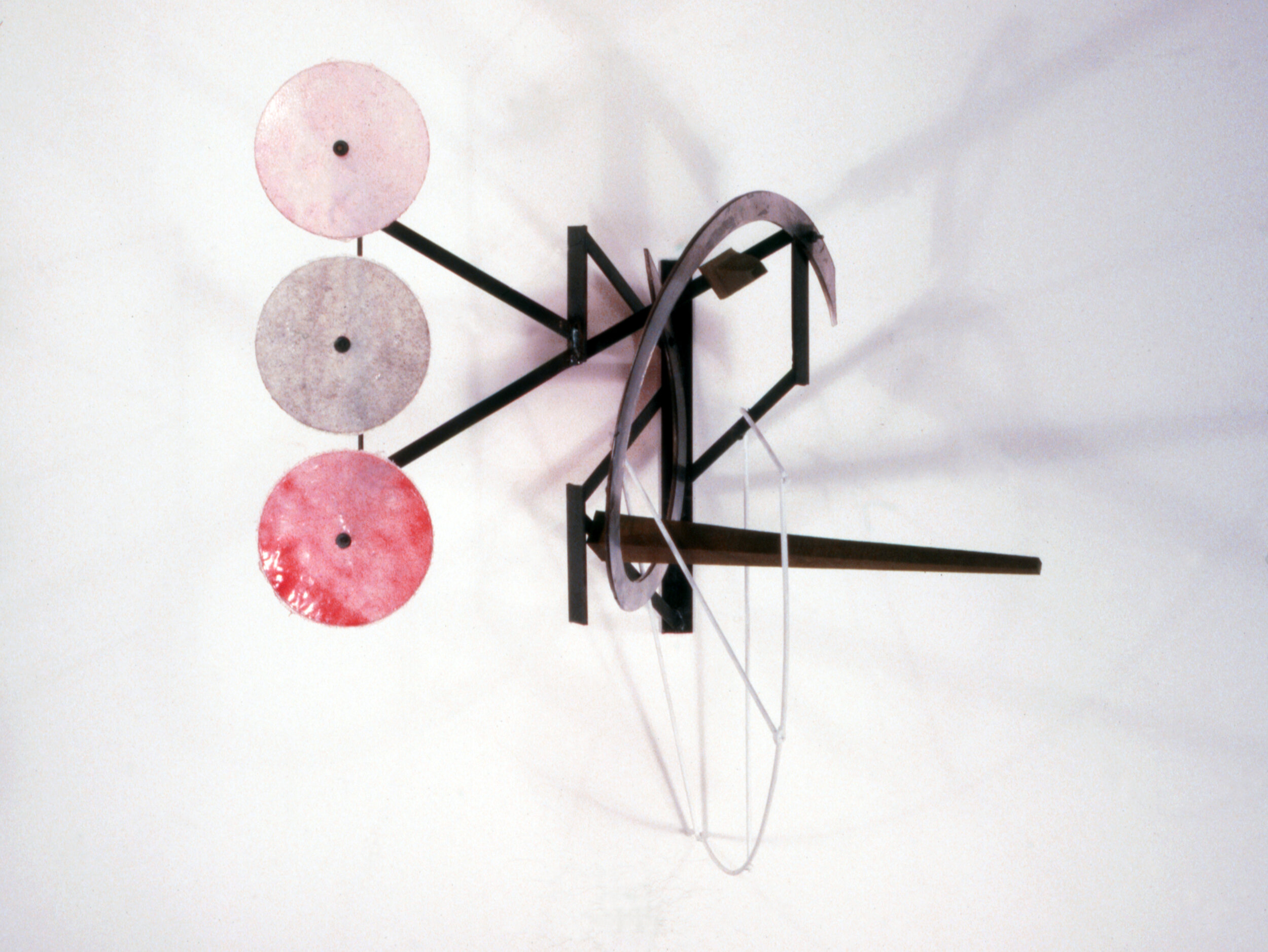

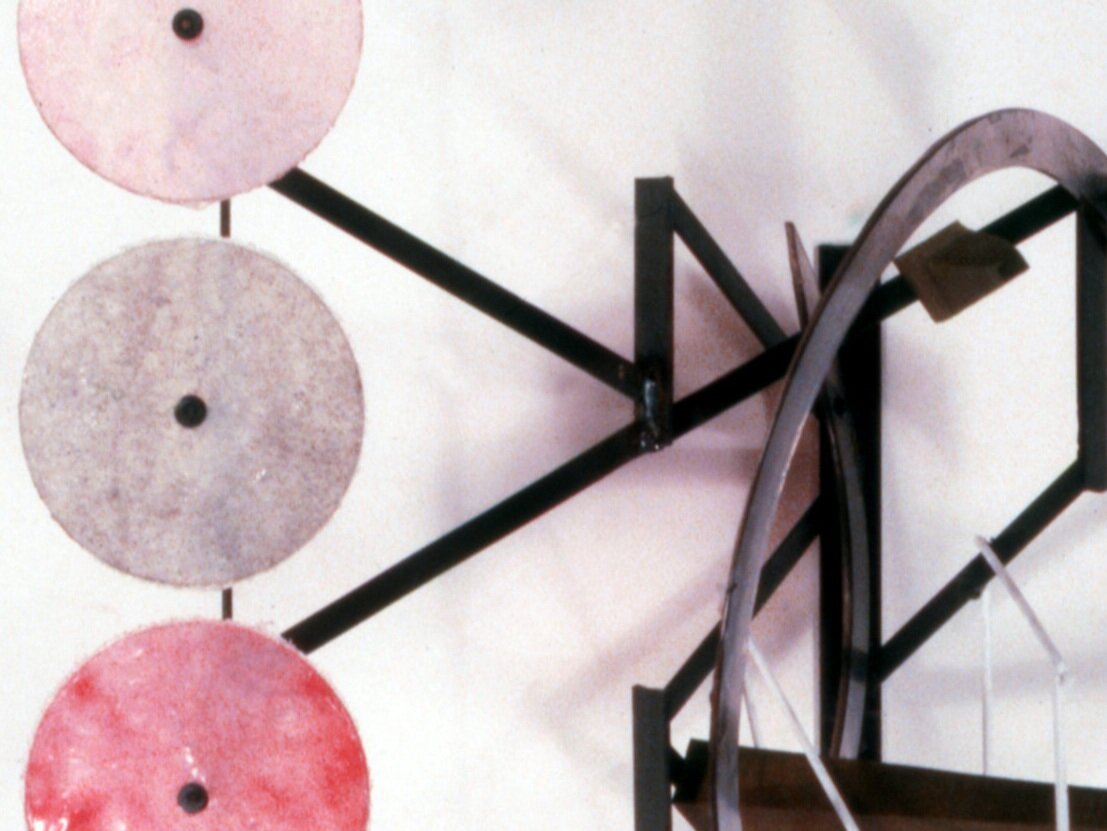

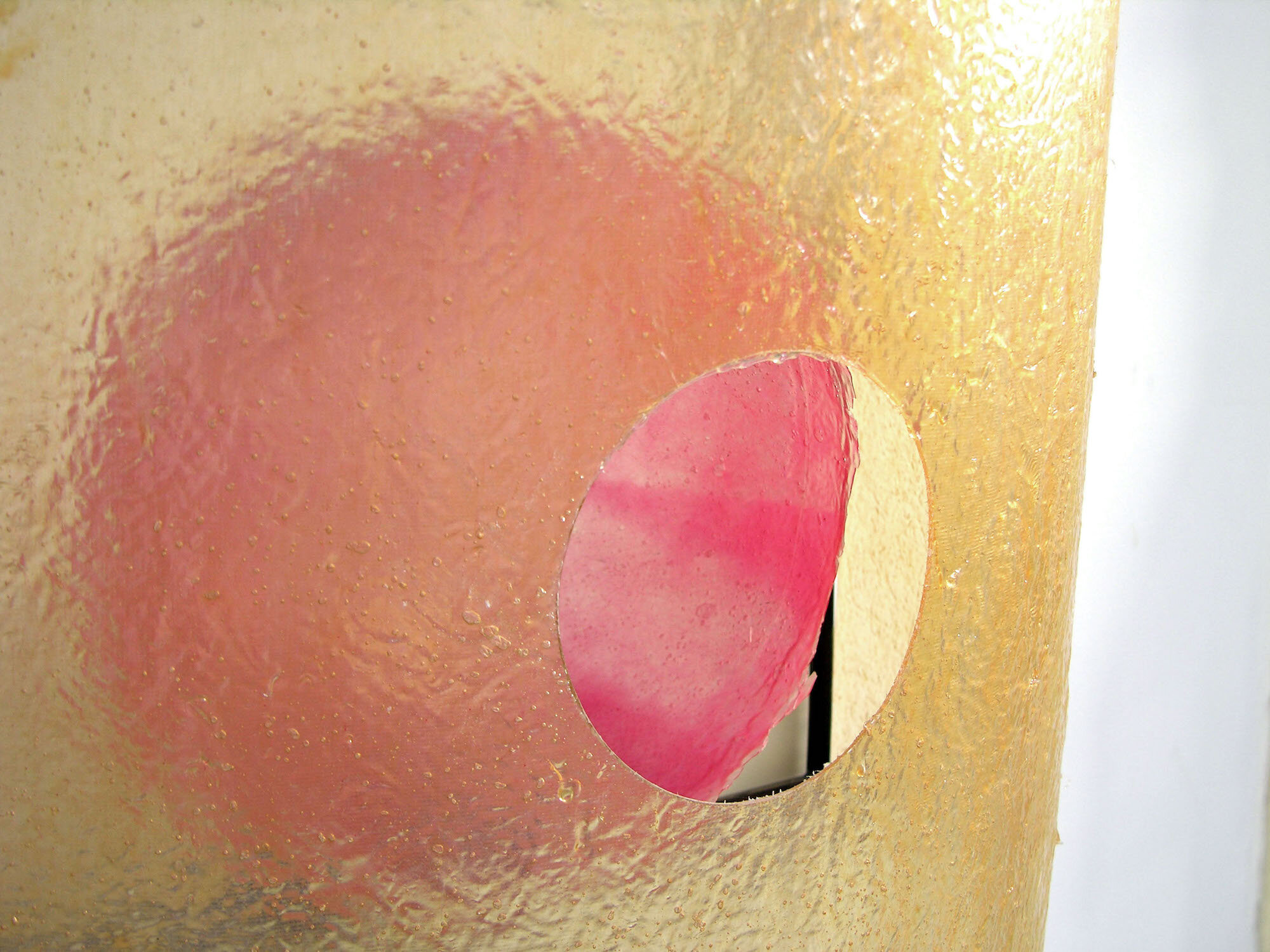

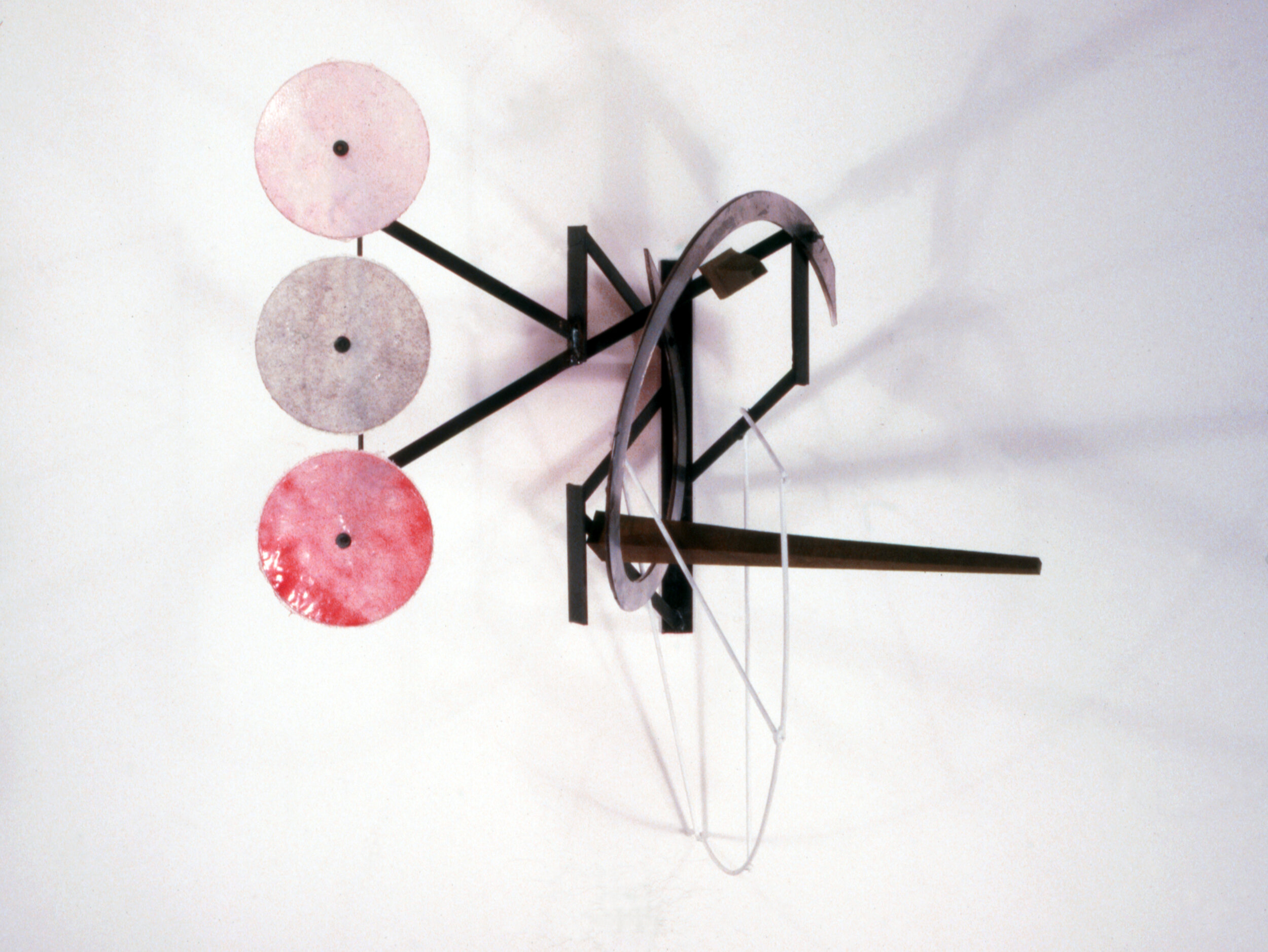

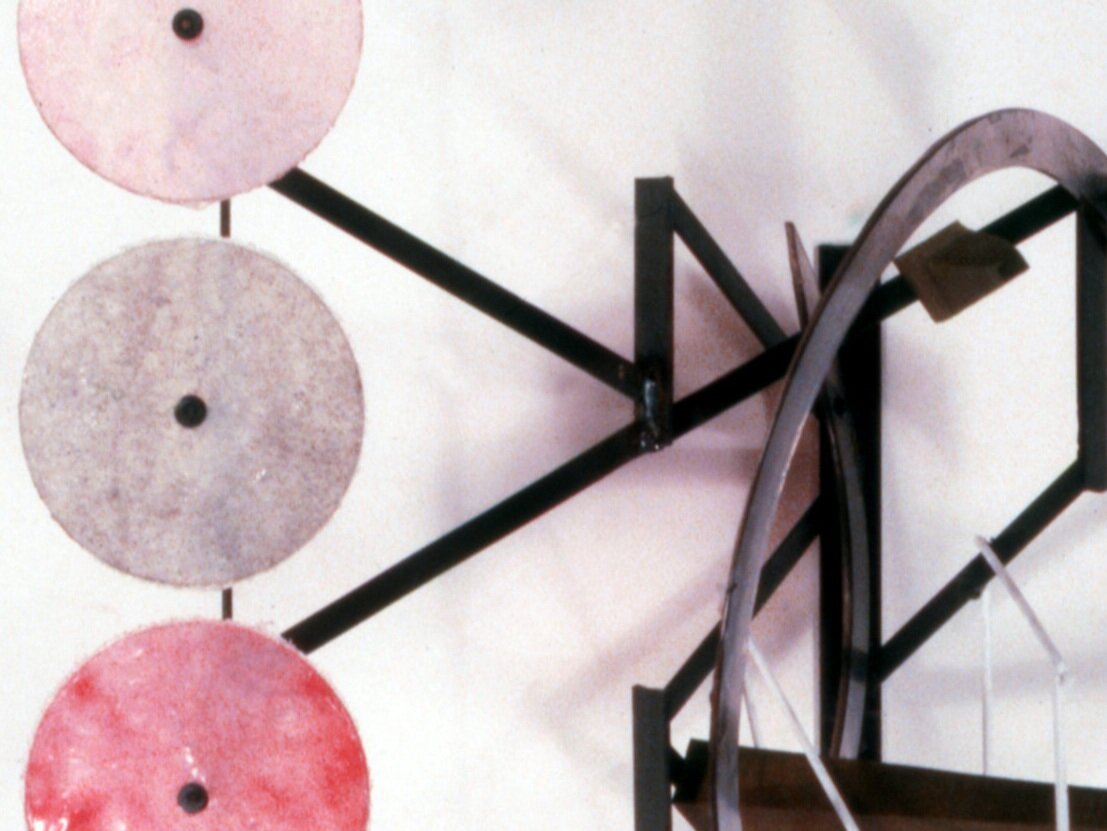

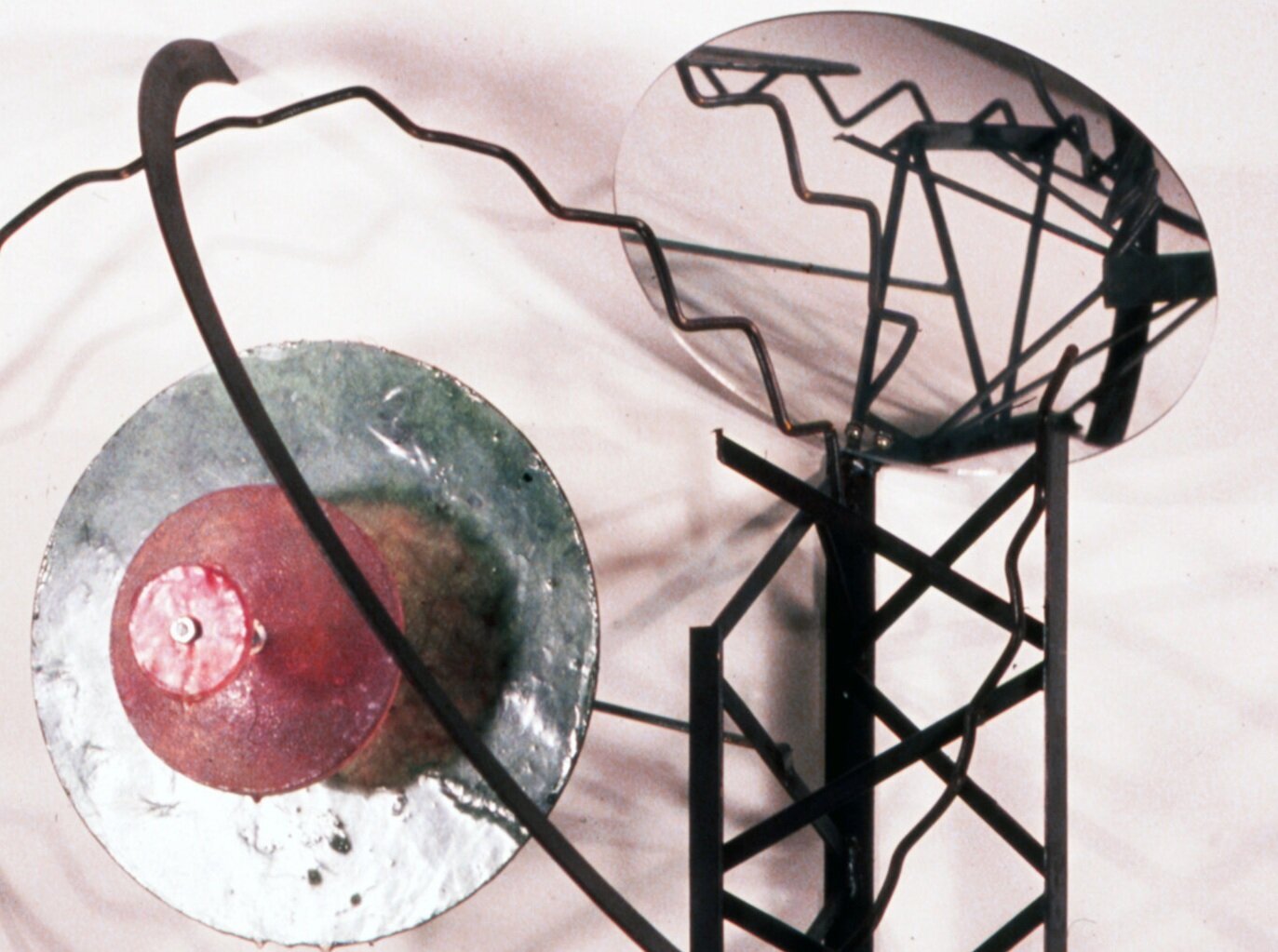

Big Wheel (1997), polyester resin, steel, 74 x 74 x 29 in (1.8 x 1.8 x .73 m)

‘Big Wheel also reflects Butter’s Interest in childhood play. A large, thin disc of translucent pink fiberglass is mounted on an axle supported by armatures; just over six feel tall, the construct suggests a delusionary mixture of Ferris wheel, erector set, and half-cucked pink lollipop. At the same time, the disc’s jagged edges recall the sawmill blades that used to be stock terror devices in silent-film suspense serial. Indeed, the works do concern themselves with suspense – not in terms of narrative, but physics.’ Justin Spring, “Tom Butter, Curt Marcus Gallery” in Reviews, Artforum MAY 1998 ( p. 148-9)

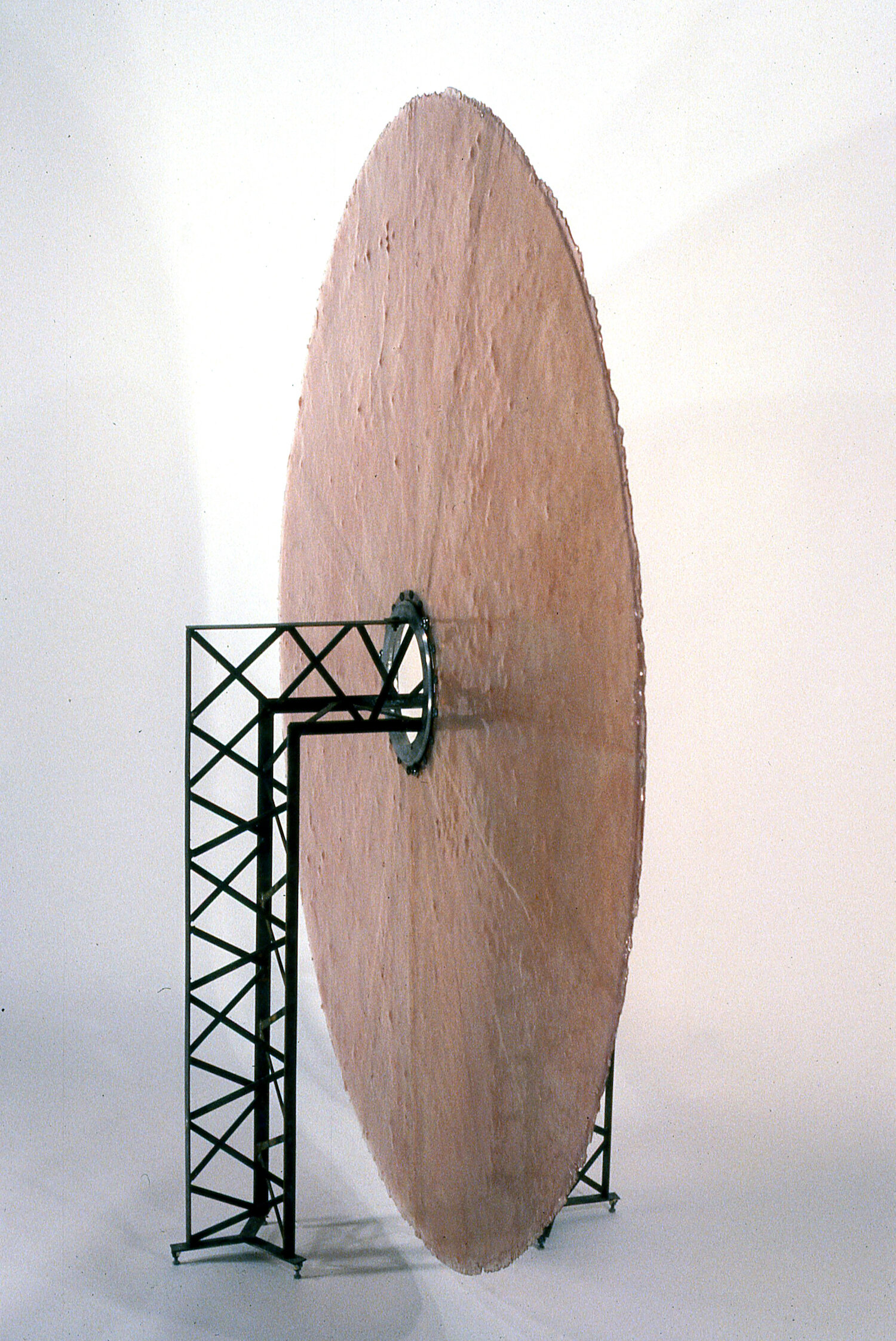

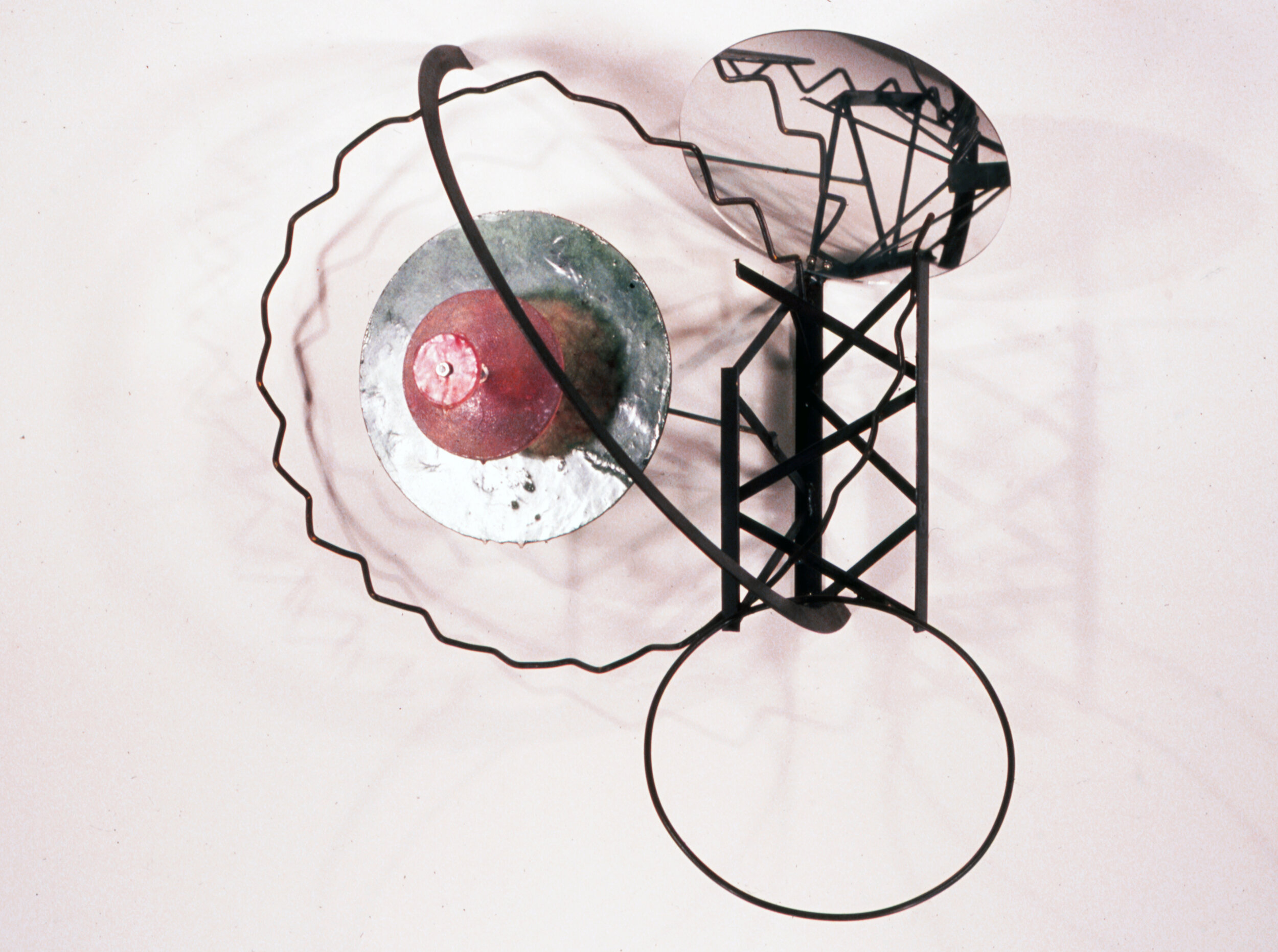

Eclipse (2000), polyester resin, pigment and steel, 93 x 50 x 44 inches (2.3 x 1.2 x 1.1 m)

detail, Eclipse (2000), polyester resin, pigment and steel, 93 x 50 x 44 inches (2.3 x 1.2 x 1.1 m)

Forge, 1996, leather, polyester resin, pigment, steel

His mixed-media sculpture conjures up images of old technological optimism only to undercut this optimism with other, less congenial images. He uses modern materials - fiberglass is a favorite - but gives these materials narrative meaning outside technology. In two pieces, ‘Metropolis’ and ‘Forge’, hands in the form of real gloves stiffened with resin crank away on big wrenches or grasp massive chains. These are big, impressive pieces that seem symbolic and bluntly formal at once. The symbols are clear enough.

The gloves suggest the heroic proletariat and the idealism of socialist labor. Like cutouts from a 1920’s Soviet poster, they suggest worker power and potential for social justice. But it isn’t long before we progress from optimism to futility. The gloves rapidly become absurd, disembodied things, extensions of invisible workers who perform their tasks in ignorance. In the simplest terms, they are symbols for alienation, nothing more. In ‘Forge’ for example, the hands seem to be pouring a length of chair from what looks like an enlarged flower petal vase into an ordinary galvanized bucket. A surrealistic trick? Not really. -Richard Huntington, “Technology, geometry and skepticism” in The Buffalo News, Tuesday February 18, 1992

Metropolis, 1992, leather, wood, graphite, steel

Butter makes metaphors - even potentially humorous ones - seem more like hard facts. The ideas he presents may be ambiguous and contradictory, but the form is not. Finally, the work may be a kind of critique of metaphor as much as a commentary on the downside of technological society. With Butter there isn’t a tinge of Chaplinesque redemption in evidence anywhere. He holds in check the potential humor of, say, a wrench hopelessly yanking on a chain welded to a floor plate.

This is no extravagant surrealistic leap the the illogical. In fact, Butter studiously avoids the standard surreal dream atmosphere by giving his strange chain pourer a flatly factual presence. The act may be absurd, but the action is believable. Butter carefully balances message and form. Form is made to tell the tale trimly, with no excessiveness, nothing overstated. The sculptures are studies in economical form, and they are pretty to look at as well. Sometimes Butter is careful and neat in his merger of idea and form. It seems to time that to look at these sculptures as formal abstractions is little more than an add-on experience. The major point has already been made, pack there with those chains and gloves. Still, these sculptures have conviction. Tom Butter is among the skeptical.

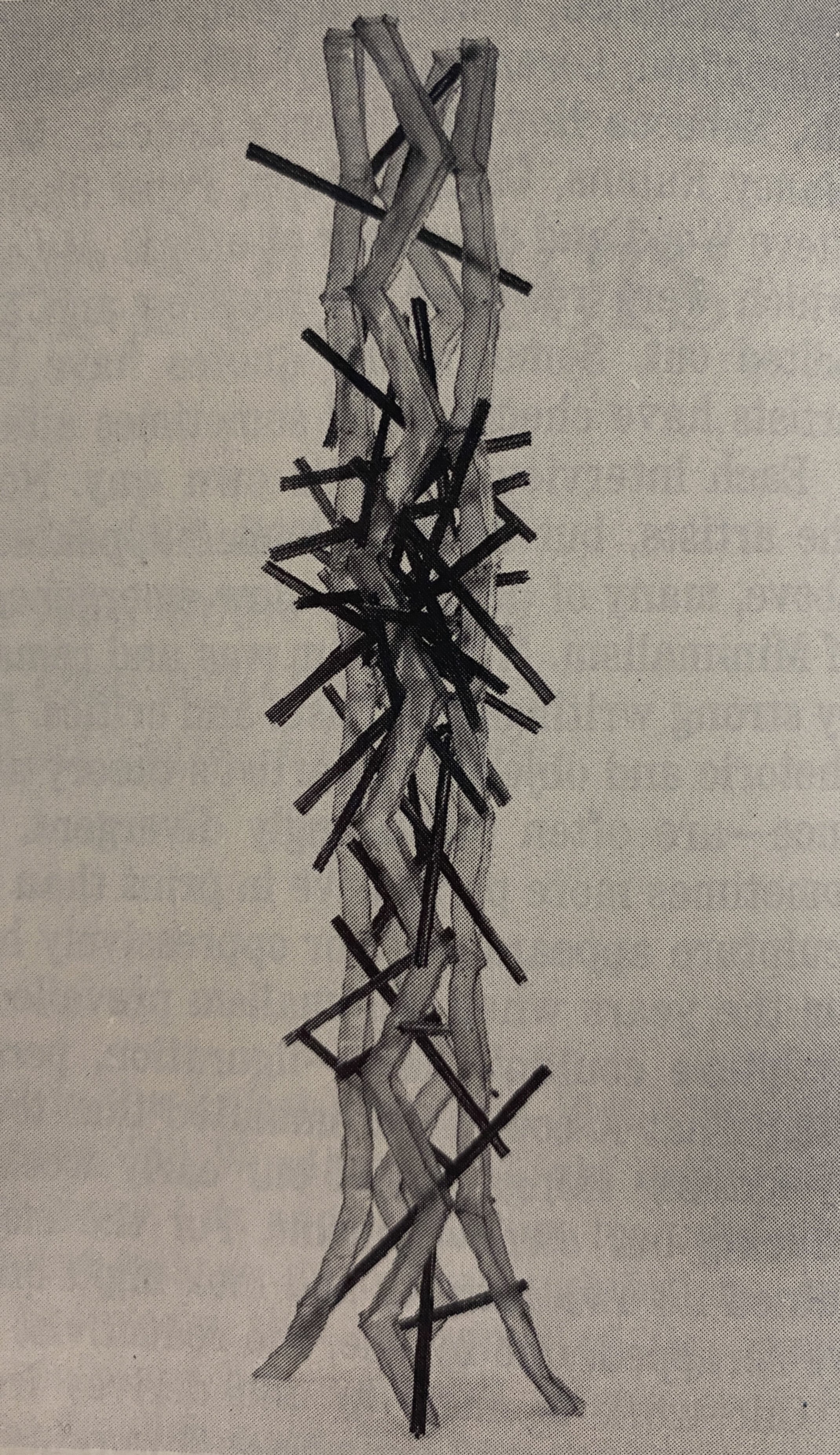

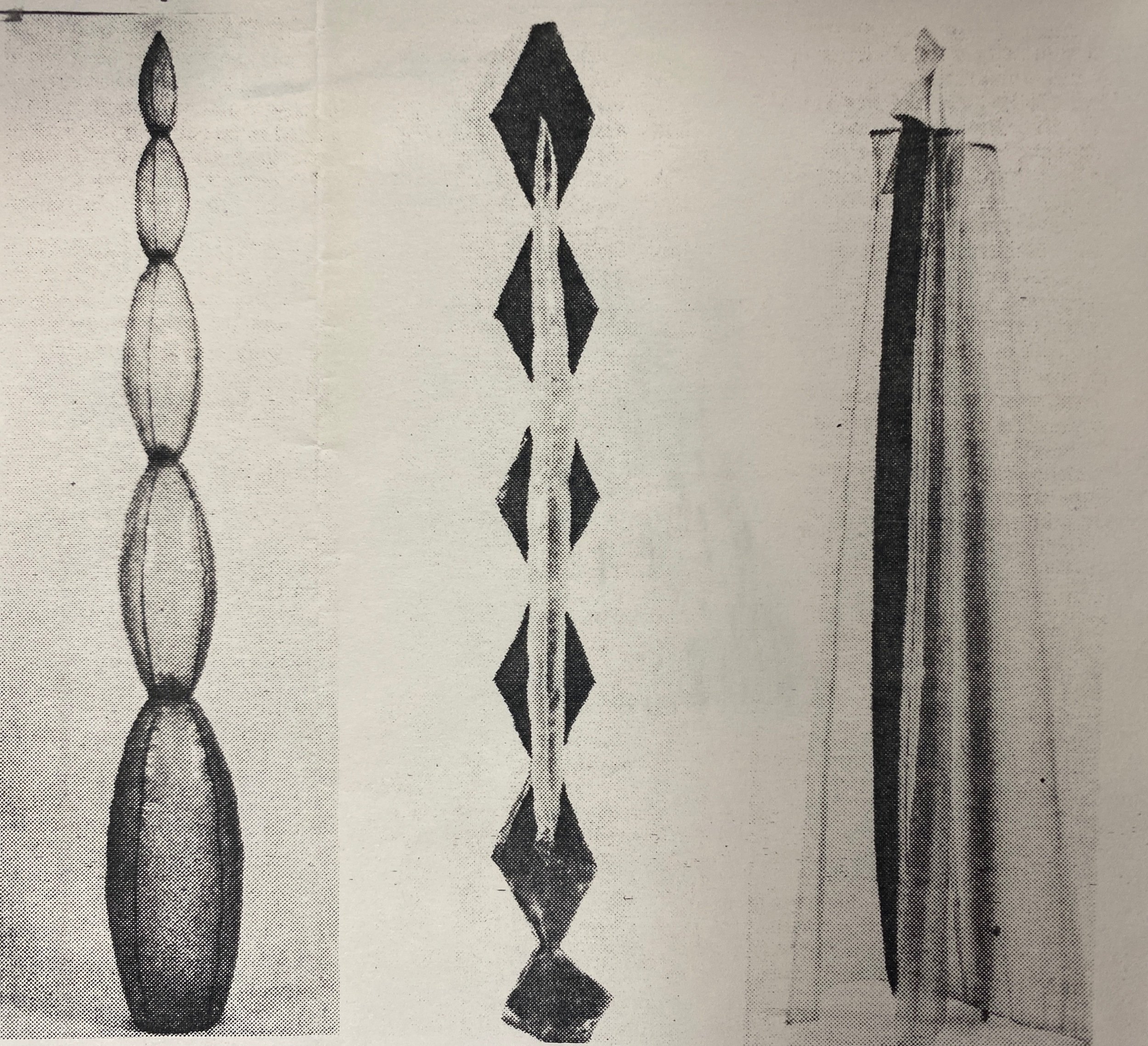

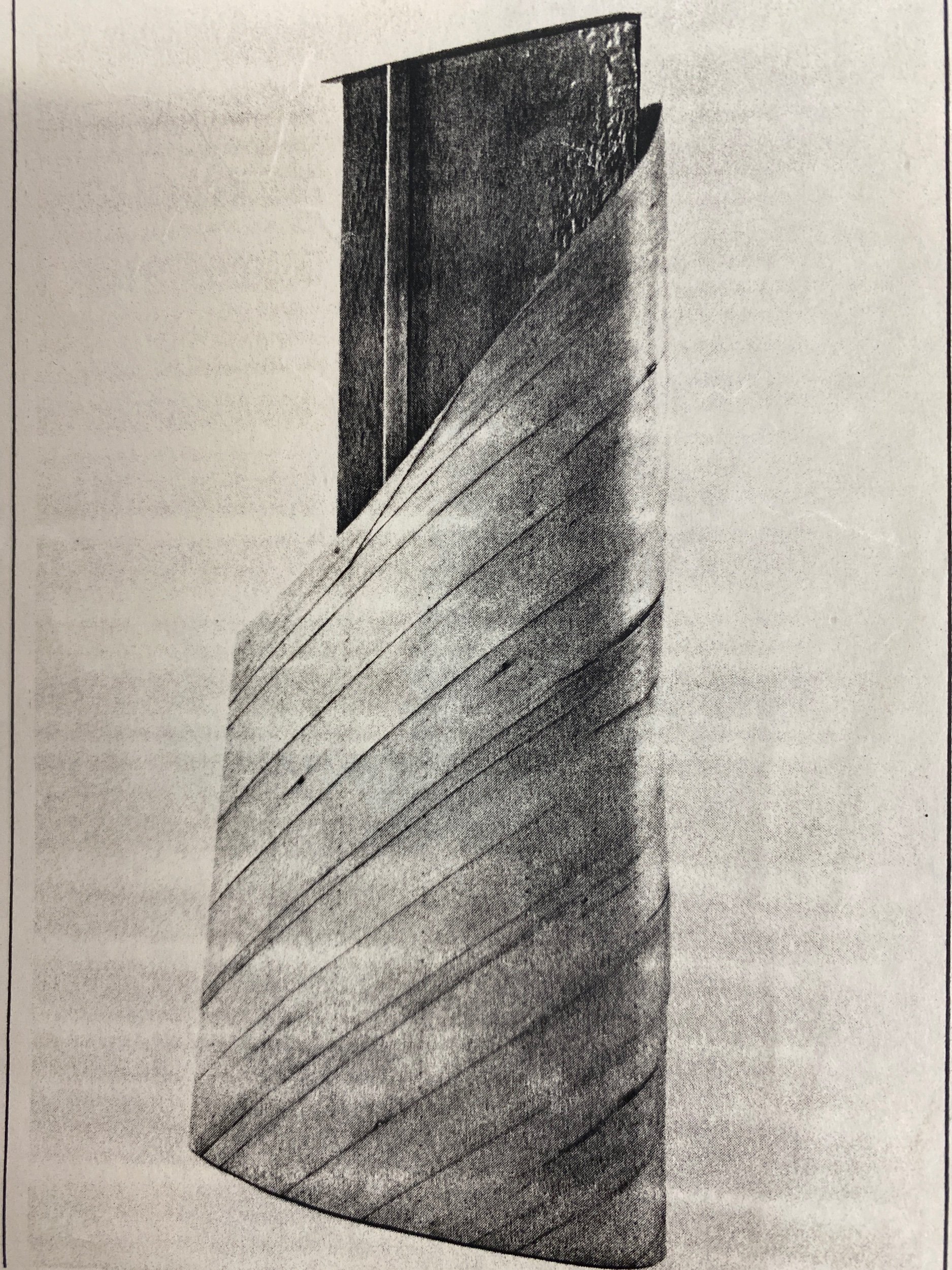

S. L.. 1982, fiberglass and resin, 84 inches high, at Grace Borgenicht

Modern sculpture is roughly divisible into open, horizontal, linear/planar constructions and closed, vertical, solid seeming monoliths. Most constructions are abstract; most monoliths are figurative or biomorphic in character. Tom Butter’s sculpture straddles this opposition: his constructivism limns a nature rampant. His pieces are at core linear, but his lines have stretched and muscled themselves up into volumetric, vertical skins evoking cylinders, obelisks, skyscrapers, stuttering lightning bolts - five to ten feet high. His lines and so his sculptures are imbued with expansion and growth; although his constructions are traditionally composed and seemingly complete, they suggest continuation or extension. They have gained the pulse we often sense in monoliths.

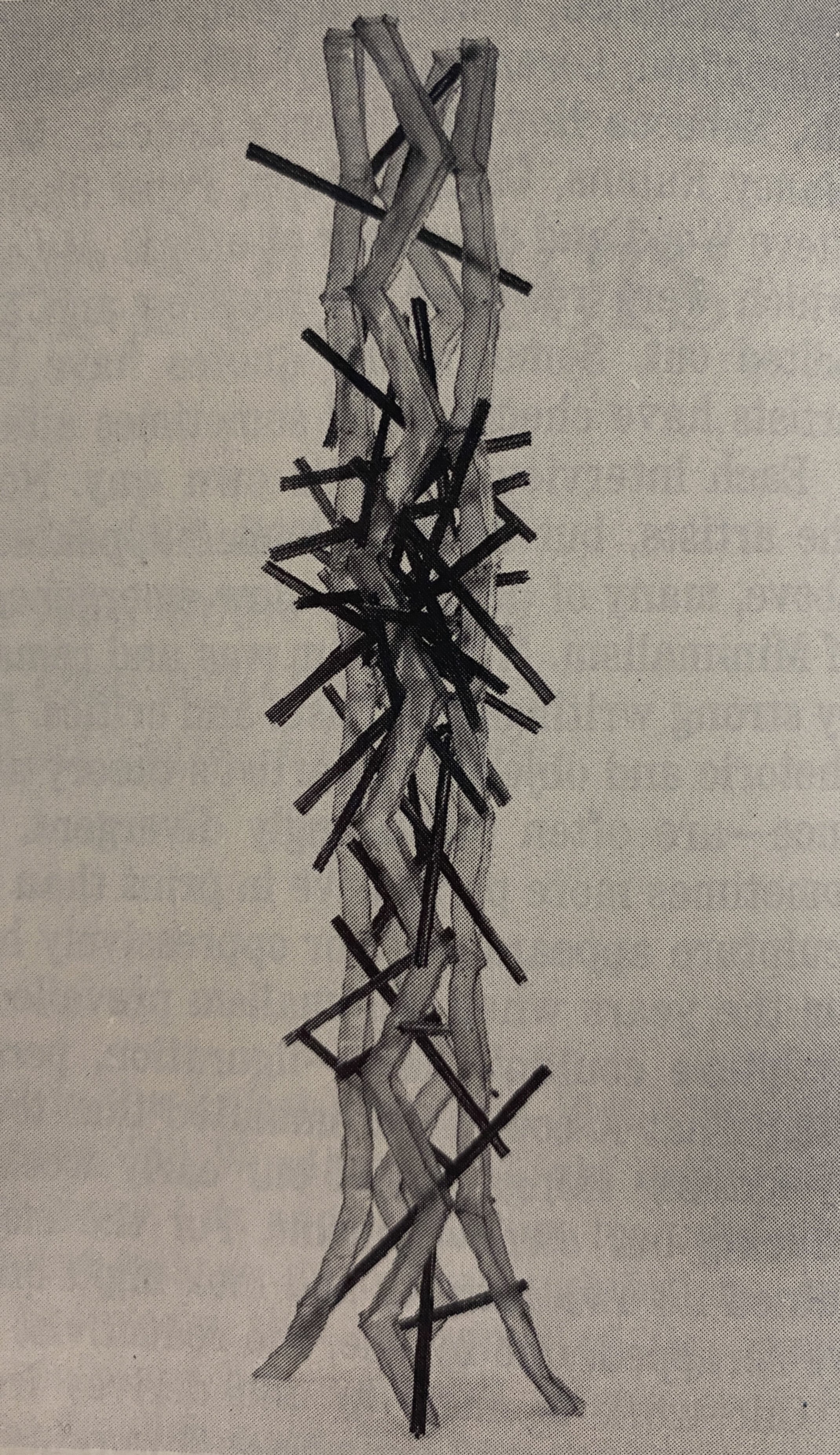

M.R. 1984, Fiberglass and resin, 99 x 9 x 11 inches

Butter cuts, suspends, guys and staples pieces of fiberglass cloth together to make his skinny volumes, which he then freezes with catalyzed polyester resin colored with dyes. His approach permits him almost to ignore gravity while working: the bottom of an element doesn’t have to support the top physically until the resin has hardened, at this time its weight is no problem. Butter generally assembles his sculptures from these premade parts, though he will sometimes shape cloth around a rigid fiberglass element that he has made earlier - the work N.B. for example. Within a single sculpture, similar shapes are similarly colored.

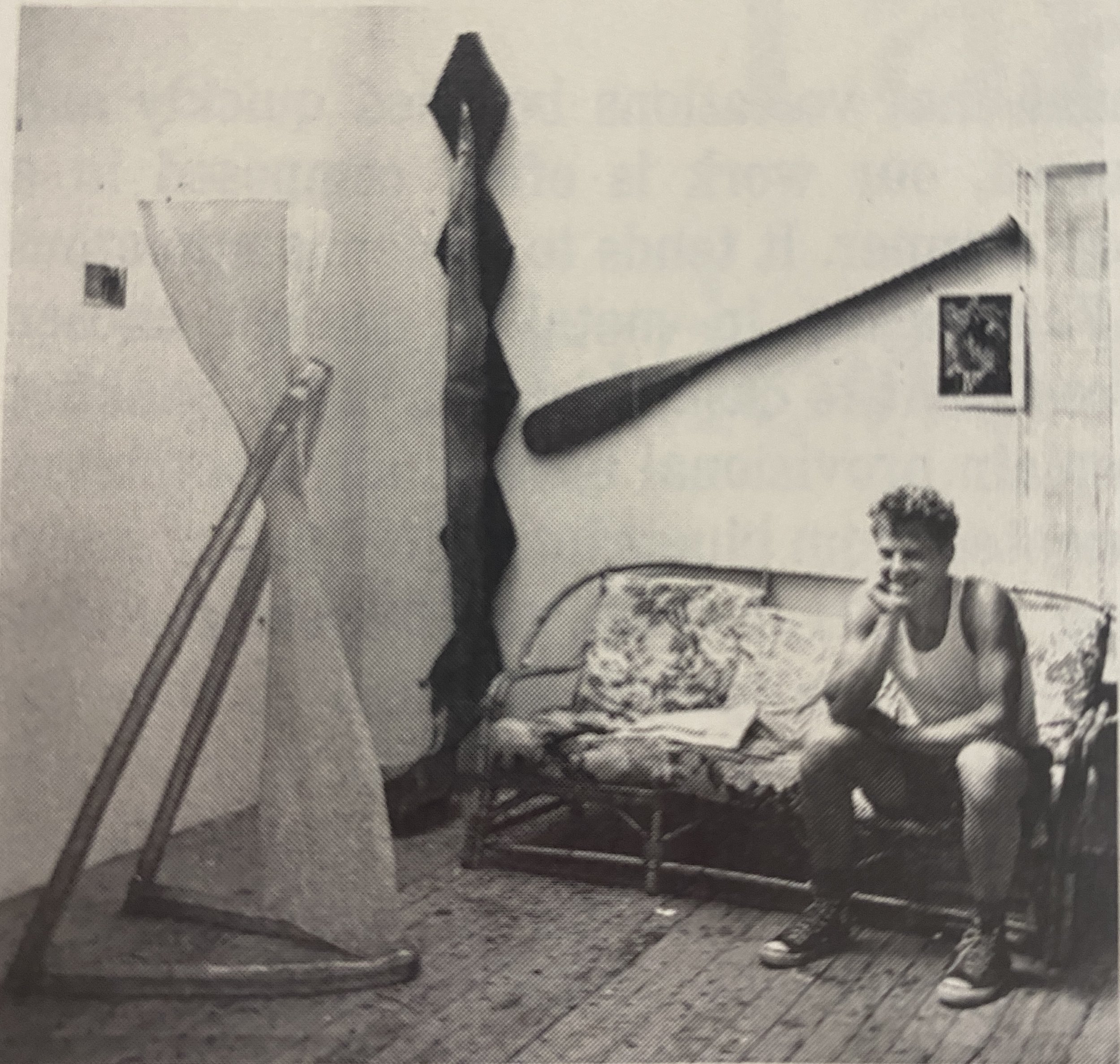

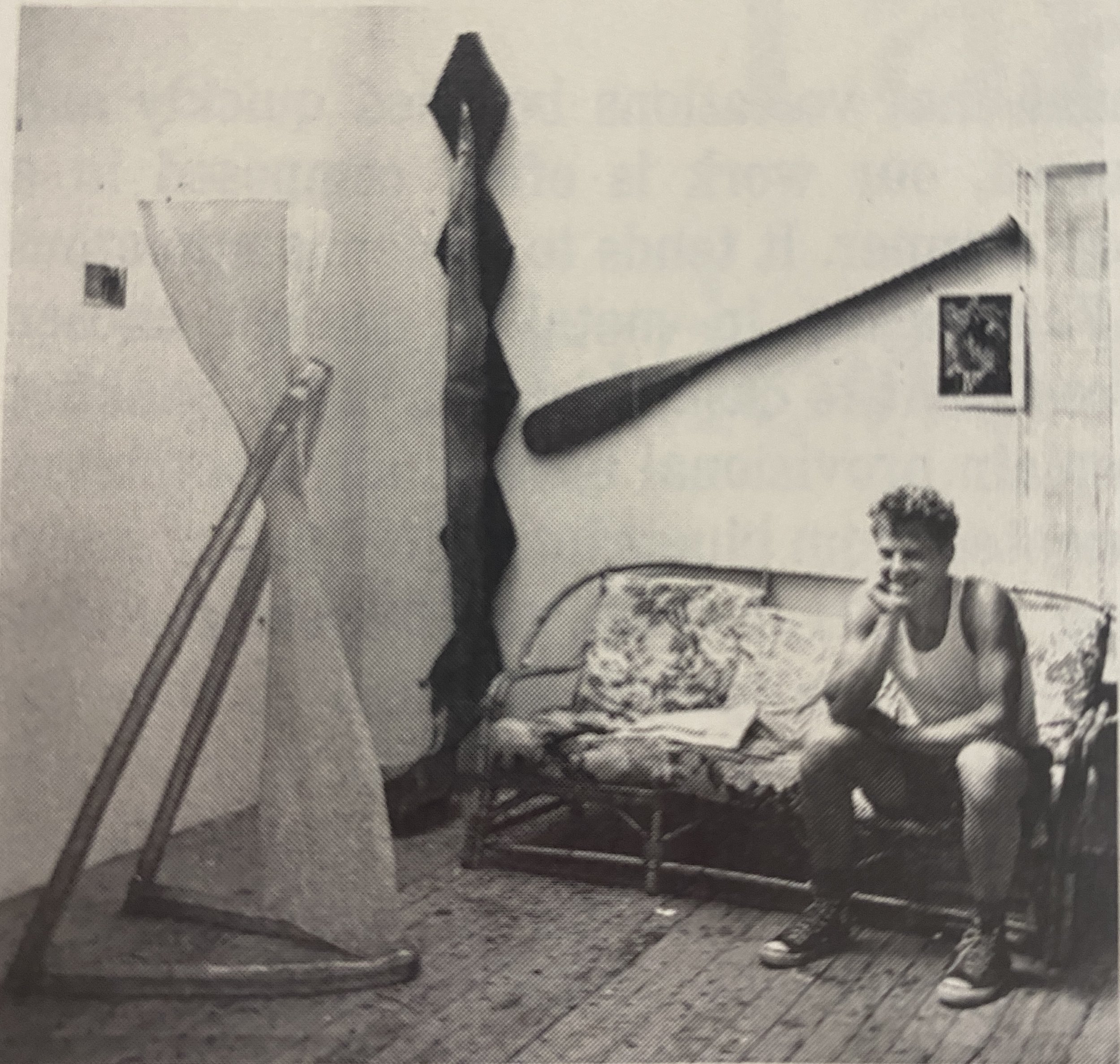

Artist in the studio with M.R., New York City, 1984

Butter is probably attracted to the resin/cloth combination for the reasons other sculptors have been: fiberglass is relatively simple to master, requires little equipment to work, can produce objects both light and extremely strong, is responsive to touch, can be ambiguously translucent, and seems to possess a surface simultaneously wet and dry. For Butter is is also a material which can be worked quickly and gesturally - in which his loose personal geometry doesn’t look sloppy.

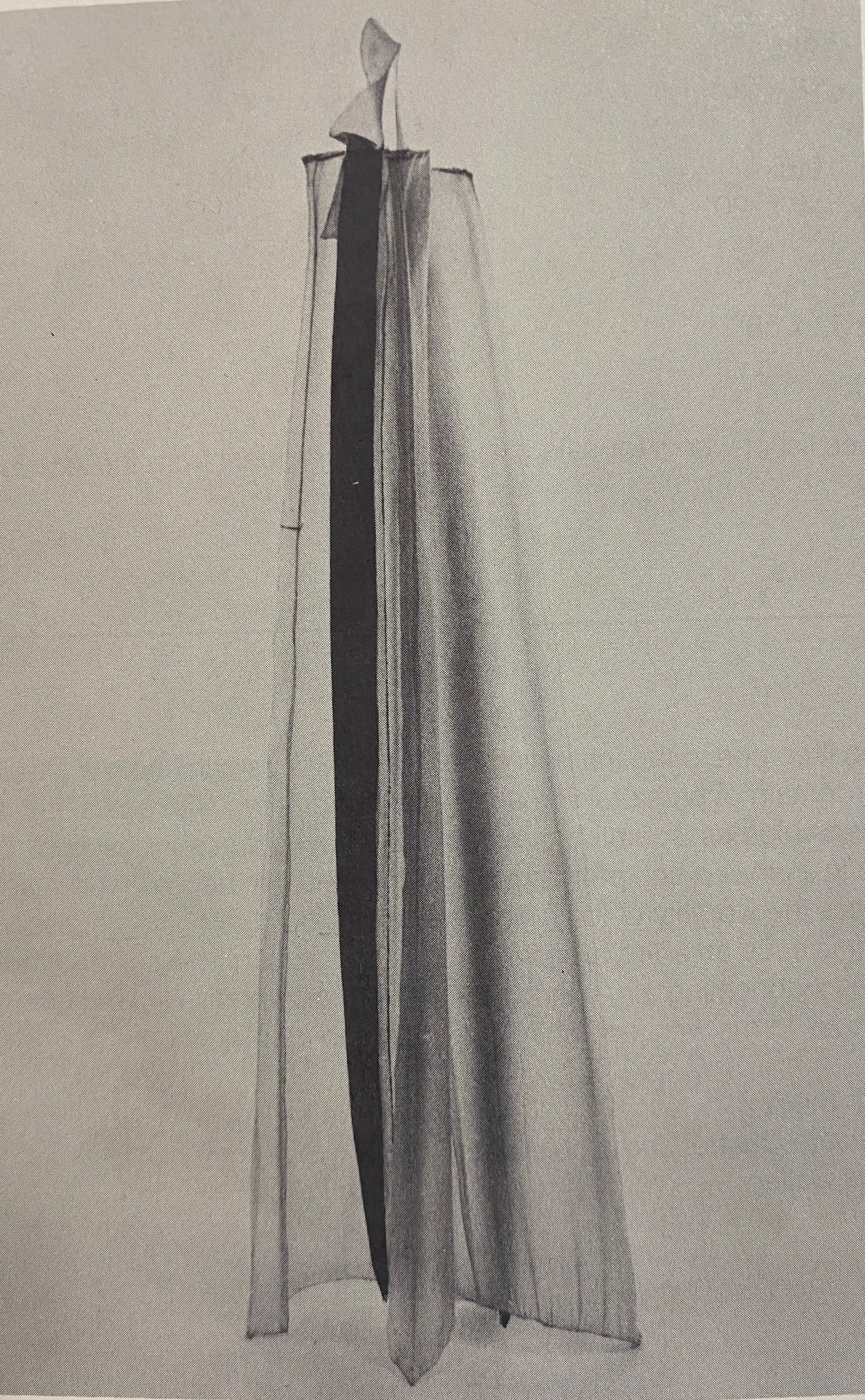

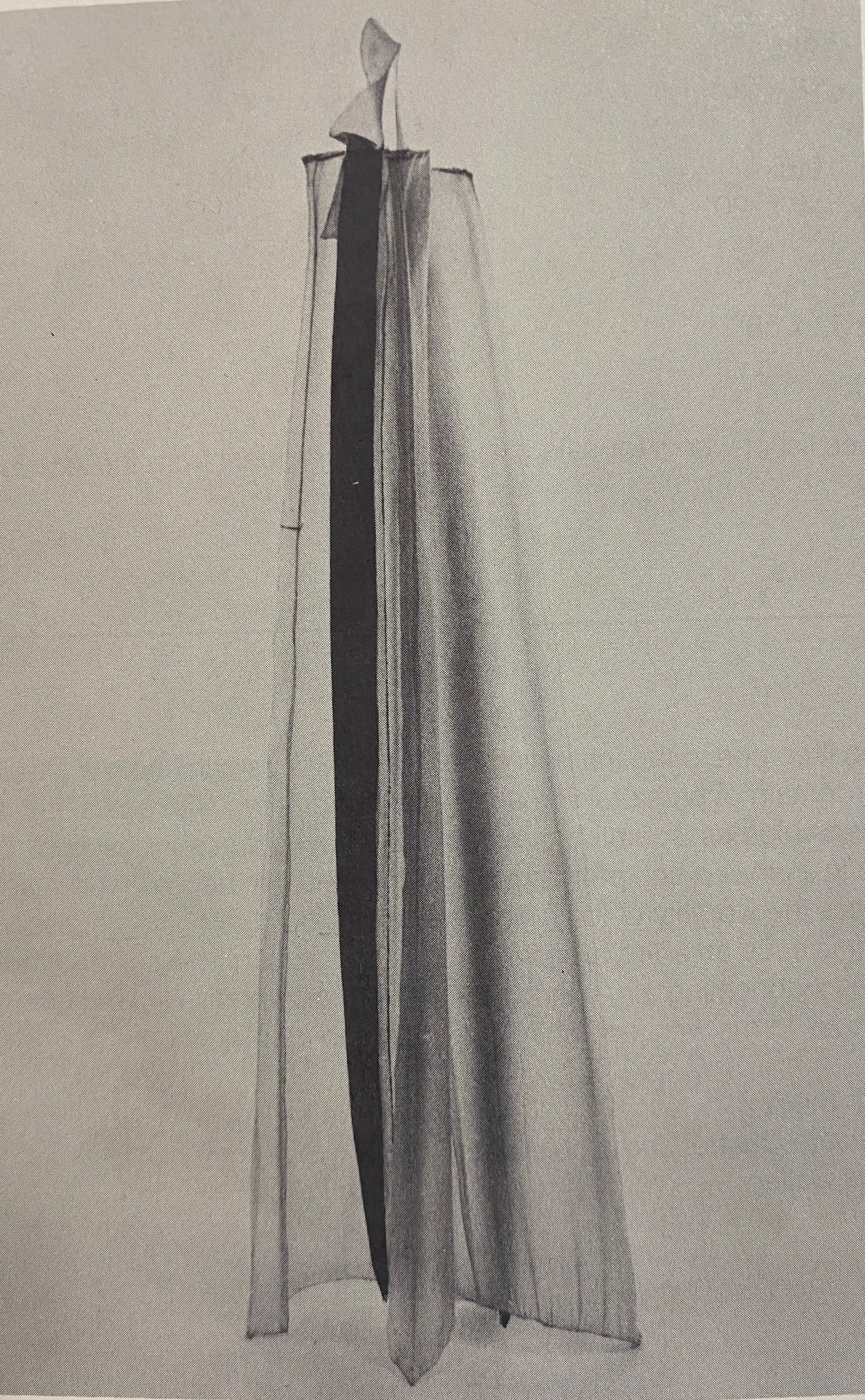

L.J., 1984, fiberglass and cloth, 101 x 22 x 11 inches

Quickness - actual and apparent - is central to Butter’s sculpture. Since he can readily make and rapidly deploy almost any volume he conceives, he recovers some of the liveliness that was central to Chamberlain’s and Sugarman’s great sculptures of the early 1960s. Although the springiness, even timidity of his forms is suggestive of growing things, it is the relationships in which he places his basically abstract parts that prompt and sustain a biological reading.

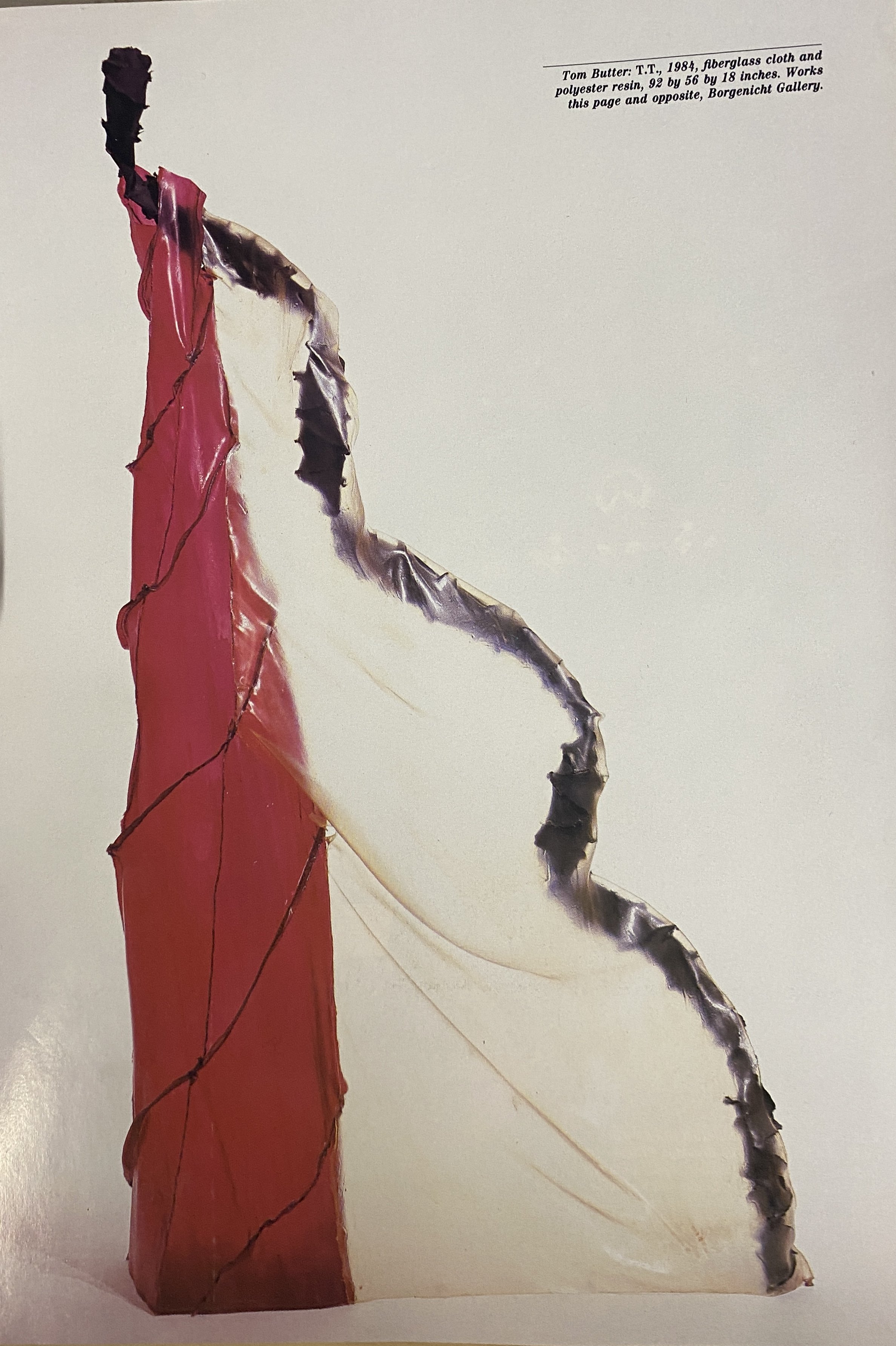

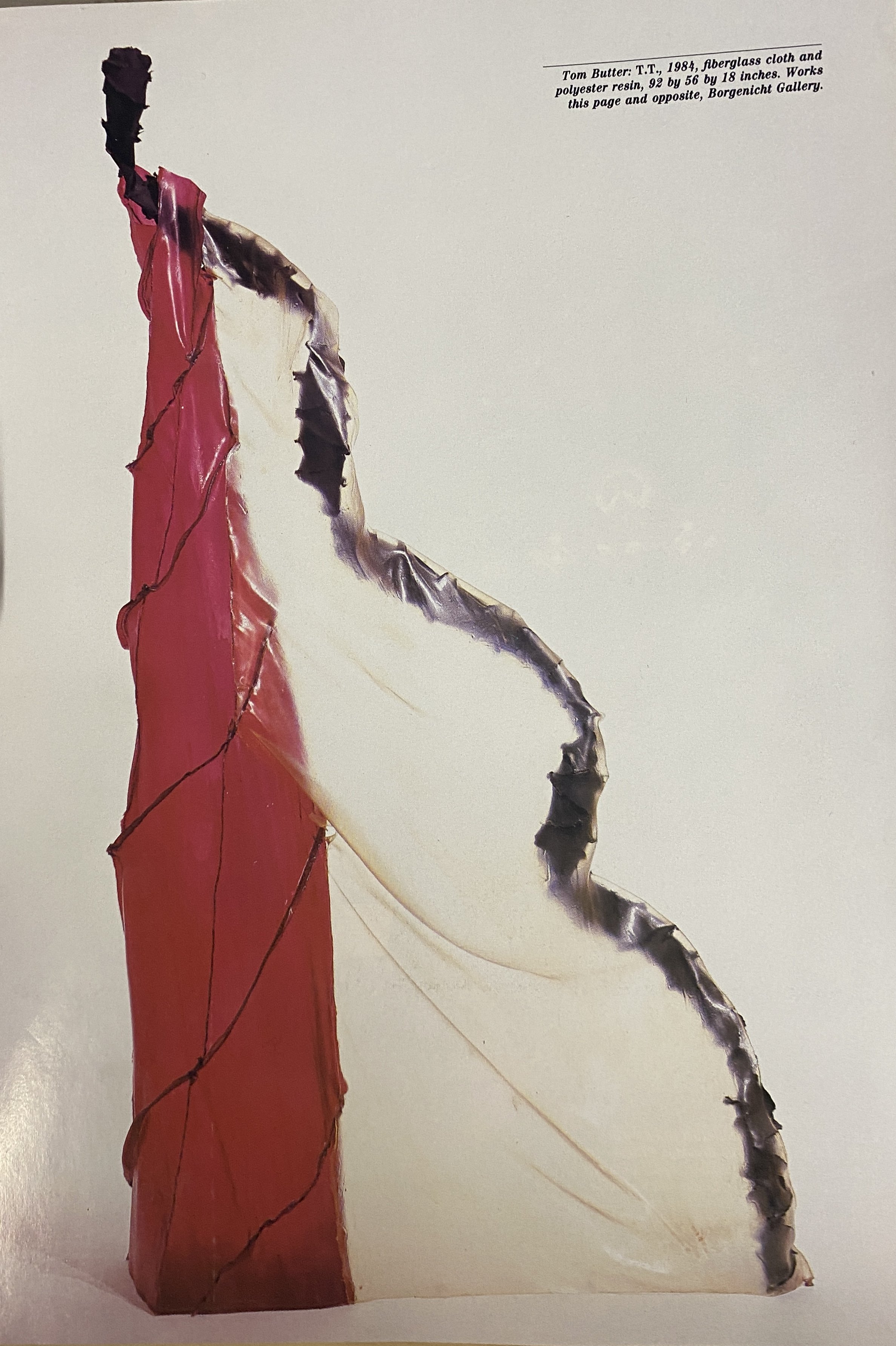

T.T., 1984, fiberglass cloth and polyester resin, 92 x 56 x 18 inches

With a couple of exceptions, the sculptures play a twisting, upward movement off a still, vertical core - actual or implied - like a vine twining around a tree, though in the sculpture the elements are structurally interdependent.

T.T., 1984, fiberglass cloth and polyester resin, 92 x 56 x 18 inches

Such a movement brings with it a suggestion of time: the pieces are ongoing, not fixed. In W. H. a swollen, red, ten-sided column, its greatest girth near our eye-level, rises up from a tight circle of dark, collapsed arcs, like a shucked ear of corn surrounded by husks. Though large, its translucency keeps the piece light; it finesses the big, bigger, biggest quality of monoliths.

D.H., 1985, fiberglass cloth and resin, 32 x 12 x 12 inches (ed.5)

Butter’s shapes aren’t unique - Noguchi’s akari lamps, Eva Hesse’s, John Duff’s, and Barbara Zucker’s sculptures are acknowledged sources - but his active handling of space is fresh. He plays the perceived hollowness of his elements of against the open enclosure of their arrangements to suggest separate but simultaneous presents.

C.B., 1983, fiberglass and resin, 6’ tall

S.L., 1982, fiberglass and resin, 82” tall

In S.L. and C.B. (his titles are people’s initials) he partially revives the stunning spatial richness and ambiguity that Constructivist-derived sculpture once had. -Wade Saunders, “Tom Butter at Grace Borgenicht”, Art in America, April 1983, p. 117

A.K., 1984, fiberglass and resin, 92 x 18 x 18 inches

Solid sculpture embodies the traditional function of the medium as a way to create and organize volumes. Some 20th-century sculpture. however, like that of the constructivists. emphasizes structure rather than mass. In structural sculpture the spatial envelope is often implied rather than directly represented by material: the skeleton of the piece takes precedence over mass and surface. Tom Butter's sculpture falls somewhere between these extremes. Butter's pieces flaunt their structure. but they also emphasize ~he qualities of their integuments, of the skins that make them volumetric.

Butter's sculptures. 'fabricated of resin-impregnated fiberglass · cloth, are light but rigid and usually translucent. Their skins are also, in a sense, their bones for every element or every piece is formed from the plasticized screening. Aside from the properties ' already mentioned. however, we also note in both collections two other salient characteristics of this sculpture: It is energized by light and color and it is suggestively tactile, so much so that the material creates an illusion of improbability.

Thus every element is hollow. Formed or "skin " shaped into bars. slabs, ‘ovoids’ and other configurations. So while the sculptures dis place volume. or else articulate it. they also enclose it within their individual components.

There's an intrinsic freedom to this kind of sculpture: one senses that the material's potential to describe. evoke and fantasize is limitless. for nothing about the forms is ordained by the material used to shape them. Furthermore, the pliable fiberglass is a more "friendly" medium than a resistant one like stone. end less liable to fracture . There's no tension In it: the material yields totally to the artist's whim.

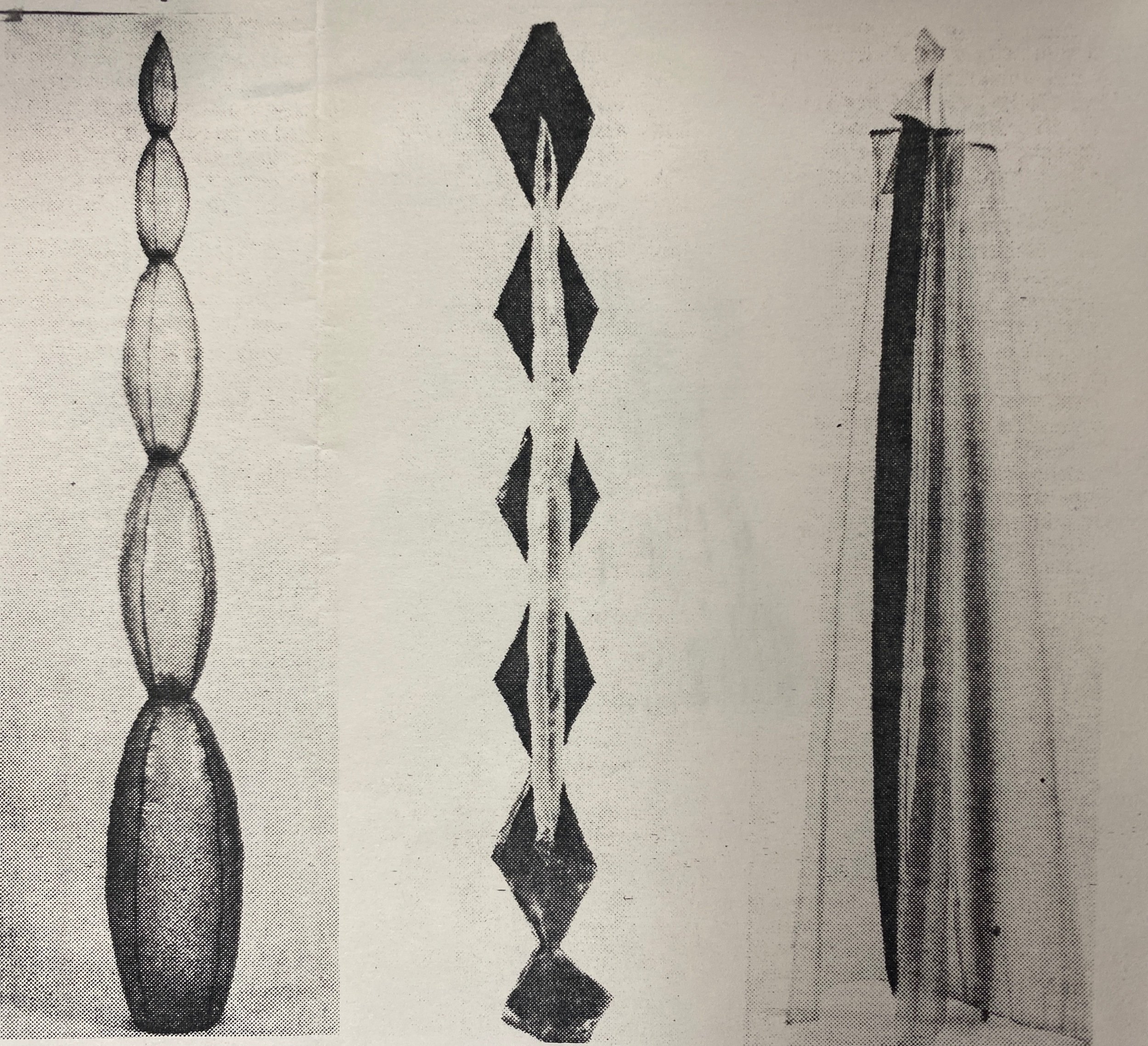

T.C.B., 1984, fiberglass and resin, 10” tall x 14” wide

The white ones looks like gelatin or ice; they project on one hand softness and airiness and on the other coldness. In either case the surfaces are delicious; because the colors are part of the material, they are resonant rather than simply reflective.

T.C.B., M.R., A.K., 1985, fiberglass and resin, color and dimensions variable

Each show contains seven pieces. Some at the Morris Gallery are ribbed, making the skin-bones contrast more pronounced. Others are vaguely biomorphic: one looks like an exotic strand of purple kelp.

A.K., 1984, fiberglass and resin, 7’8” tall

Still others employ a "hairpin" element that forms the basis of the extrapolations at Lawrence Oliver. The "hairpin" form used as legs, or stacked. or joined with a lozenge form - becomes in both collections symbolic of the melding of surface and support.

-Edward J. Sozanski, Art combining different ideas about sculpture, The Philadelphia Inquirer, ~THE ARTS Thursday, November 21. 1985

Catapult, 1993, wood, graphite, wire thread, 27 x 81 x 120 inches

Tom Butter’s sculptures of the late ‘70’s and early ‘80’s, eccentric abstractions related to work by John Duff and Eva Hesse, were made of fiberglass. But fiberglass, like abstraction itself, turned out to have problems – indeed, physical hazards. Butter reduced his use of the material and began to put it at arms length (sometimes quite literally) as wood, metal and various kinds of manufactured objects, including work gloves, found their way into his work.

In The Balance II, 1993, 80 x 120 x 11 inches

One of the strongest sculptures in this recent show, In The Balance II, measures a stack of ruffled wire-mesh disks against a large, upright fiberglass plate whose shape and position suggest a gong, except that is vibrates with light rather than sound. The disks and the plate appear at either end of a slender metal arm supported by a vertical column; a wire-wrapped ball marks the intersection. Palming this ball from above is a stiffened leather work glove – the had of an unseen deity (or an artist?) tipping the scale. As a metaphor for Process Art, this is funny, deft, and unabashedly corny.

Silver Lining / Five Days Without Water, 1993, fiberglass, steel, resin

Fiberglass appears in the works in other ways that make it seem a stand-in for art itself, difficult to handle and resistant to interpretation. In Silver Lining / Five Days Without Water, oversize fiberglass petals sprout from the top of a quasi-figurative metal totem as if from a mad Easter bonnet. At the risk of a little absurdity, Butter is engaging a range of altogether serious issues, of which form and process are only the beginning. In Figure of Speech it shows up as a kind of deflated bladder, a vestigial organ tethered to an attenuated support by a snaking arcing length of iron chain.

Hand to Hand, 1993, fiberglass, resin steel, and leather gloves

Another equally radical form of bodily dissociation is enacted in Hand to Hand, which seems directly descended from Bruce Nauman’s famous Hand to Mouth, except that in Butter’s version the torso is replaced by a rolled piece of wire-threaded fiberglass. Cast-metal work gloves stand in for hands, their cuffs spooled with wire attached to the wall above; this is a puppeteer’s version of the steel-driving art-worker, equal parts Richard Serra and Wizard of Oz.

Head Spin, 1993, fiberglass resin, steel and wood

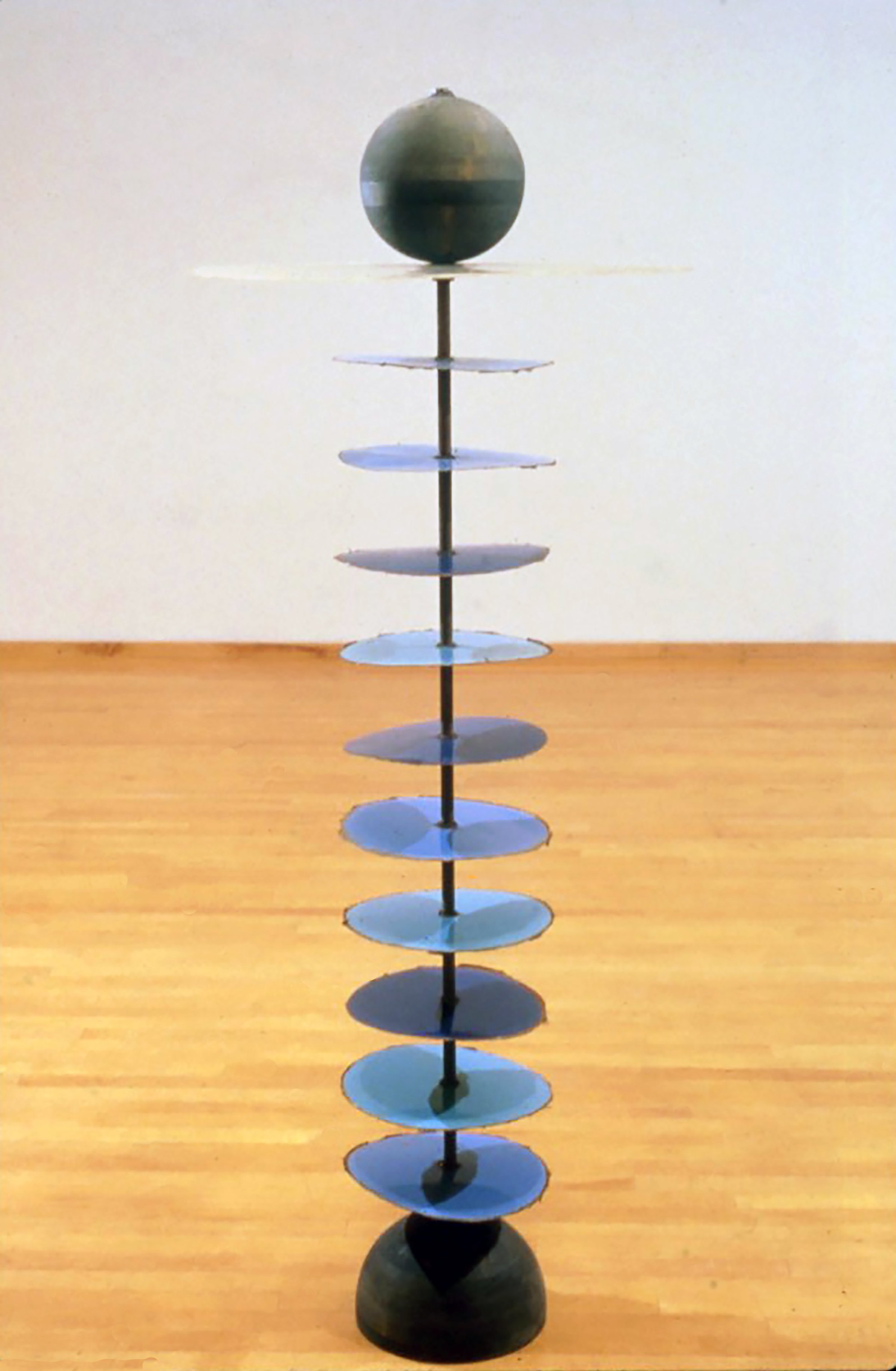

In Head Spin, a series of metal disks strung along a human-sized metal spine is topped with a large fiberglass plate that proffers a featureless wooden head as if it were John the Baptist’s on Salome’s platter.

Catapult, 1993, wood, graphite, wire thread, 27 x 81 x 120 inches

Catapult brings a ghoulish slant to the question of gravity and ways of escaping it. Resting on the blade of a long, slender oar is a blackened human skull. A nasty thing ready to be propelled into our faces, this skull is to mortality what the leather glove is to transcendence: a joke, talisman, a place-marker for an unanswered question. Catapult’s staginess is characteristic of Butter’s current work, in which faked equilibrium and disembodied figuration challenge the premises of organic abstraction.

-Nancy Princenthal, ‘Tom Butter at Curt Marcus’, Art in America, December 1993 (p. 98-99)

Night Train, 1998, synthetic polymer resin, pigment, and steel

‘In his recent show, Tom Butter presented eight works described as kinetic sculptures. But their kinesis was amusingly elusive. Only one seemed to earn the name: Night Train (all works 1997), a large steel wheel suspended by a perpendicular column sheathed in fiberglass, revolved just perceptively.

Night Train, 1998, synthetic polymer resin, pigment, and steel

A light touch, however, set the piece into smooth, sure rotation, and it turned out that all but two pieces, Two States and Dive, could be activated by a bit of manipulation (though some has such a limited range that they seemed barely to jiggle).’ -Justin Spring, “Tom Butter, Curt Marcus Gallery” in Reviews, Artforum, May 1998 ( p. 148-9)

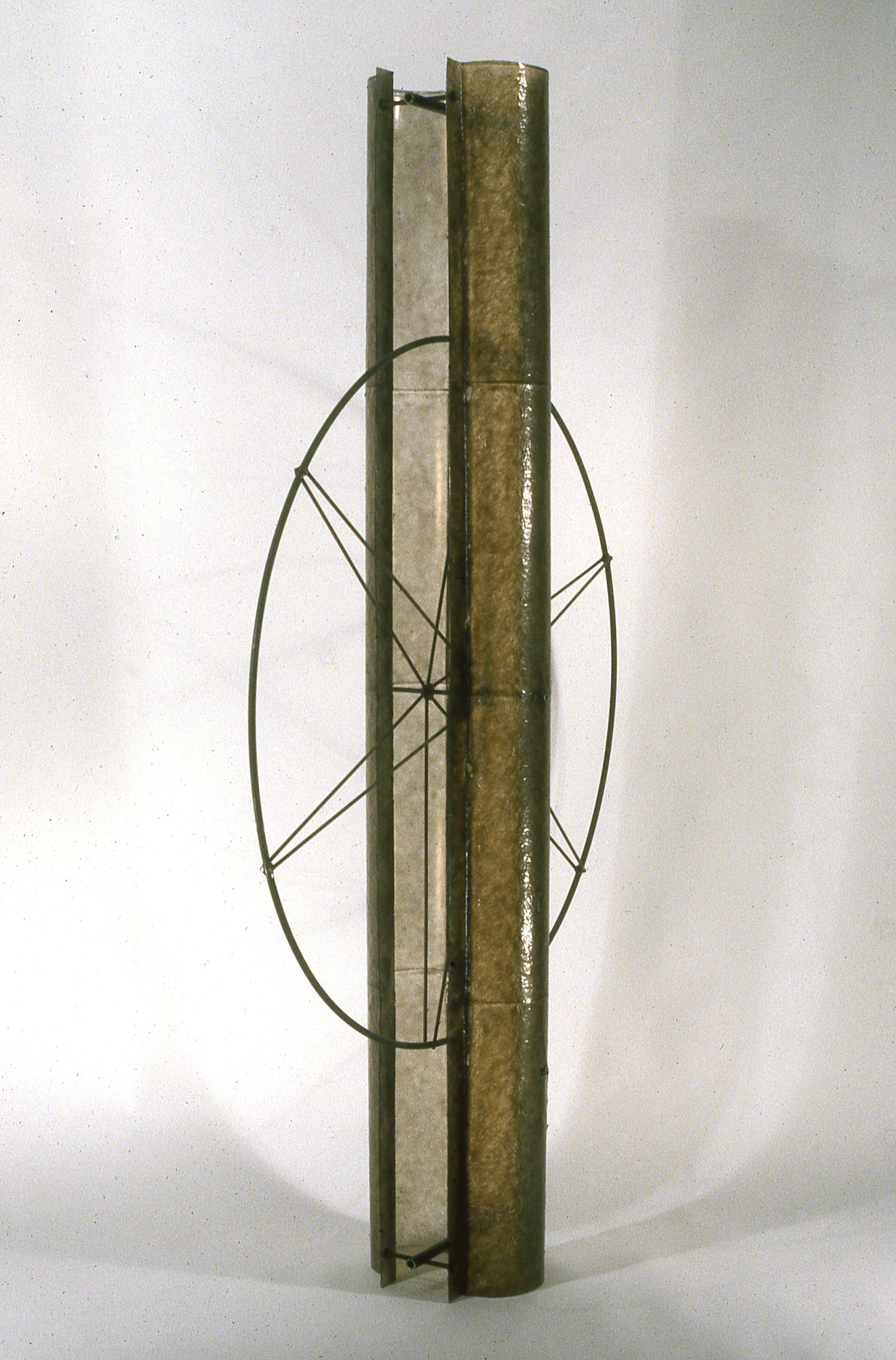

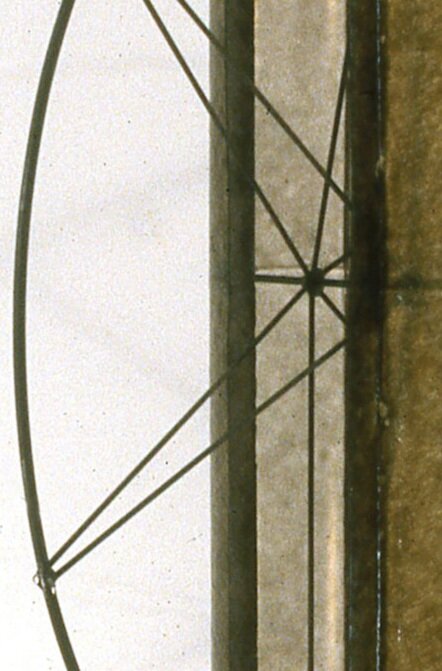

Lode, 1986, polyester resin, pigment, steel, 86 x 50 x 34 inches

Tom Butter’s approach to making sculpture has always involved taking chances. These may be procedural, such as testing the limits of how fiberglass flows and, not, its marriage to wood, or conceptual, based on the design of an object. The empirical directness with which he works warrants consideration. Each of his pieces has constructive implications. And to acknowledge this constant forward momentum is to laud the candor and verve with which his recent work is initiated, developed and sustained. Butter has worked with fiberglass since 1979. A malleable material receptive to subtle inflections of touch and color, fiberglass can be cast or molded into various shapes.

Butter has always pushed his abstract work towards ambitious scale and intricate configurations. Earlier pieces such as P.R. and M. W. set a standard for monumental free-standing work that aggressively occupied space and investigated for- mal strategies balanced between rigorous geometry and amorphousness. The severity of their modular shapes and edges was softened by Butter's tendency to anthropomorphize. And the serial regularity with which a motif developed was masked by a quirky, idiosyncratic impulse enlivened by color and a surface that quivered and shimmered-like "skin."

By emphasizing the "organic" potential of fiberglass, Butter's work has an affinity to earlier work by·~a Hesse and Bruce Nauman. A preoccupation with abstract eccentric shapes and natural forms rendered through.an empirical rapport with materials is worth noting here because it ·not only underscores a dominant sensibility in contemporary sculpture but reflects a deeper desire to synthesize formal strategies ness, the work also gains solidity. of a dress - has a rightness on intuitively, but his pieces fight and emotional impact without re- sorting to traditional narrative or figuration. Numerous methods involving diverse media and techniques have achieved this end and explain, at least in part, sculpture's present breadth and vitality.

The marriage of fiberglass and in Butter's recent work signals a significant change. The combination of two different media generally requires an initial period of familiarization, an implicit give-and-take that eventually stabilized in compatibility. Butter’s decision to introduce wood (maple and poplar) has its positive ramifications. Enhanced by new texture, color and openness, the work also gains solidity.

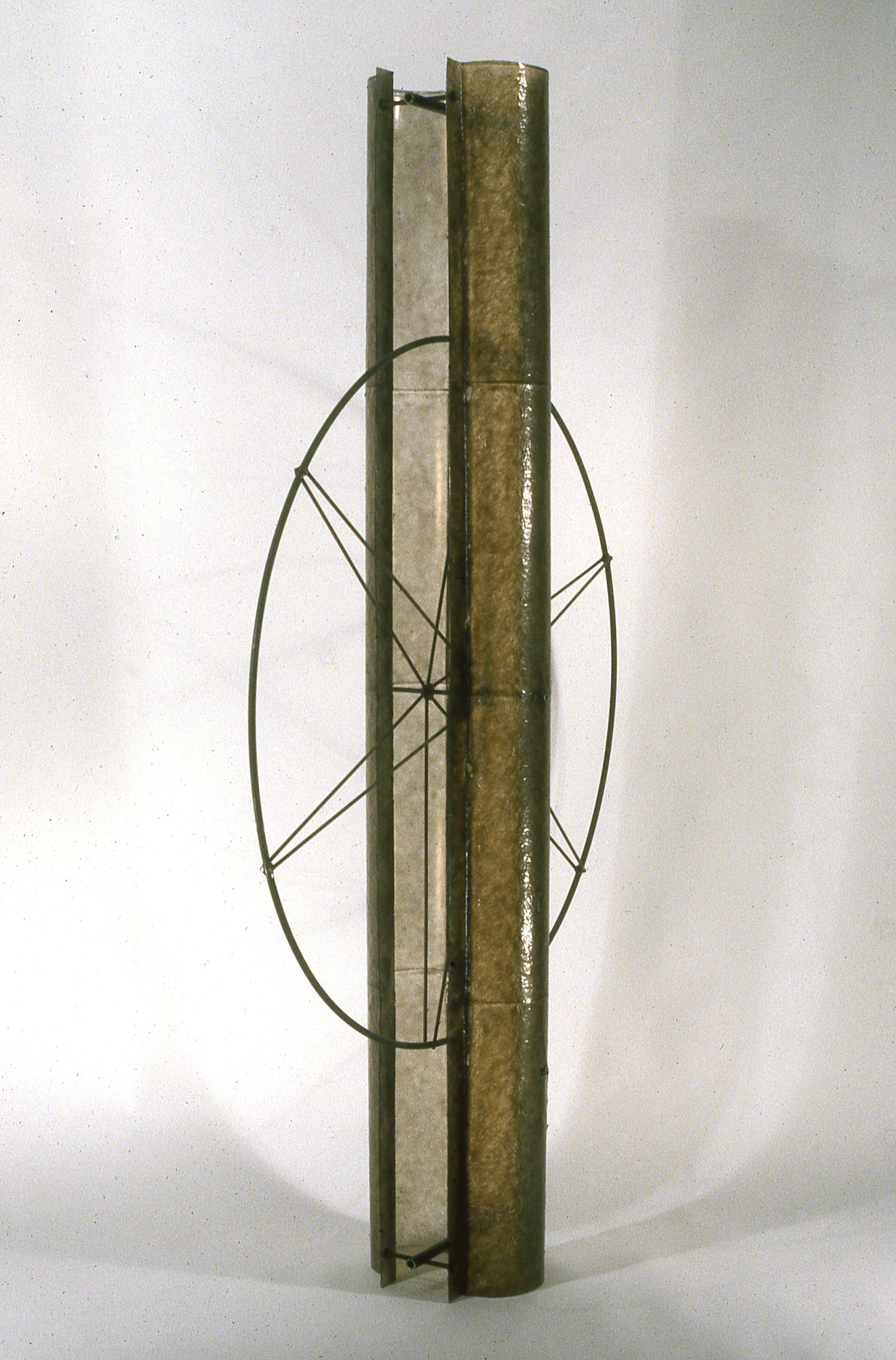

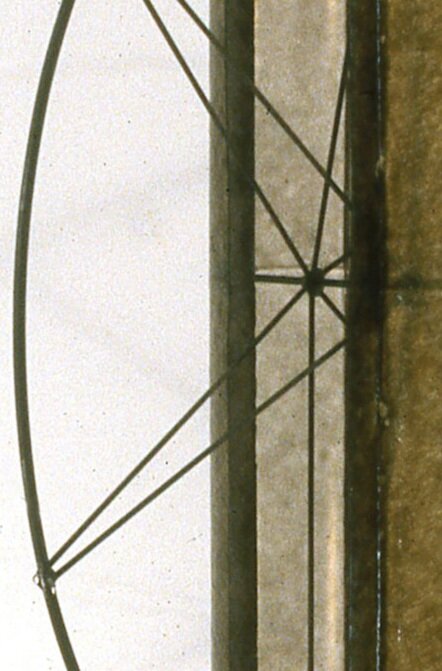

In Lode, for example, the draping of resin-colored fiberglass over, under and through an elliptical poplar frame . delicately studded with brads and bridged in one section by a clear sheet of fiberglass, not only demonstrates dexterity and control (without seeming finicky) but embodies the kind of experimental rigor and imagination that distinguishes the best of Butter’s work.

Lode, 1986, polyester resin, pigment, steel, 86 x 50 x 34 inches

Everything about this piece, its subtle projection of fins beyond the edges of its wooden frame, the rippling furrows of its fiberglass membrane that fan out at the bottom like the tail of some great fish or the hem of a dress, has a rightness on the edge. When Butter pushes the physical extensions of his materials, the results are rewarding. Butter’s wall sculpture pushes in a new direction. Considering its material aspect, a comparison with John Duff’s reliefs is instructional. Whereas Duff’s model is reductive and elegant, Butter’s is exuberant and rough around the edges. For all of their formal acrobatics, surface contortions and twisting, Duffs pieces have a graceful poise at ease on the wall. In spite of their residual signs of process and color activation, these objects achieve a "classical" perfection. Butter also works intuitively, but his pieces fight against perfected decorum, stability and homogeneity. In Hand, for instance, materials collide and slide into each other. Butter seems to accept the paradox of making ‘wall’ sculpture by stressing the tension implicit in this presentation. -Douglas Dreishpoon, “Tom Butter at Curt Marcus: October 4-30”, Arts Magazine, January 1987

In Irons, 1986, fiberglass resin, and maple, 7 feet tall

Some blocks away from that corner, Tom Butter’s sculptures at Curt Marcus neither shone nor glittered. Made of plywood and fiberglass, they need never be polished, an occasional dusting will do. Rather than volumes displacing or carving out space these sculptures are envelopes. A translucent skin is wrapped around an empty core. The space the pieces seem to take up, as opposed to their physical space, has the form of an irregular bubble extending out about a foot from the surface. This bubble seems to suck one into itself while, at the same time, the sculpture is within the bubble is retiring away.

While DeMaria and Koons use costly, industrial products, Butter employs inexpensive, do-it-yourself materials. His work suggests the hobbyist's basement or the moonlighter's garage workshop. His work is handcrafted, but in the suburban rather than rural sense: homemade boats, custom-designed cars, tool sheds. Yet this class of objects appears through inference rather than reference, from materials and techniques more than the forms themselves. His mass-produced materials are put to wholly personal uses.

Butter's sculptures tend to be organized in dualities: skeleton/skin, outside/inside, fiberglass/plywood, opacity / transluency. They also tend to have two distinct sides, from one side the other is invisible. To move around the piece is to be surprised. Once the piece has been circumnavigated, the relation .of side to side becomes apparent, but each retains its autonomy. Apart from the major vertical thrust of his floor pieces-they loom up from the ground like splitting pods-no single part reaches out to grab space. The work keeps to itself. Butter is interested in the negative space of internal volume but not in the eccentric negative space that would be produced by limbs or extensions. If he worked with human forms he would probably concentrate on the torso. And yet, these pieces are about lightness and light - lightness of touch, of gesture, of technique. They do not defy gravity, but they are not excessively troubled by it. One person could probably move them, just as one person made them.

But are they too light? Do they betray a nostalgia for easier times when the typical American male asked for nothing more than an eternal weekend of leisurely bricolage? The underlying confidence and evident charm of these works puts us at our ease. They suggest a solid life without sharp edges, an imagination on a human scale. The reductivist lebensraum of De Maria and the cynical paucity of Koons say more about the present state of things than Butter's inventive constructs, but then again, diagnosis is cheap, cures altogether too rare. -Meyer Raphael Rubinstein, “Sites and Sights: Considerations on Walter De Maria, Jeff Koons, and Tom Butter.” Arts, March 1987, p. 20–21.

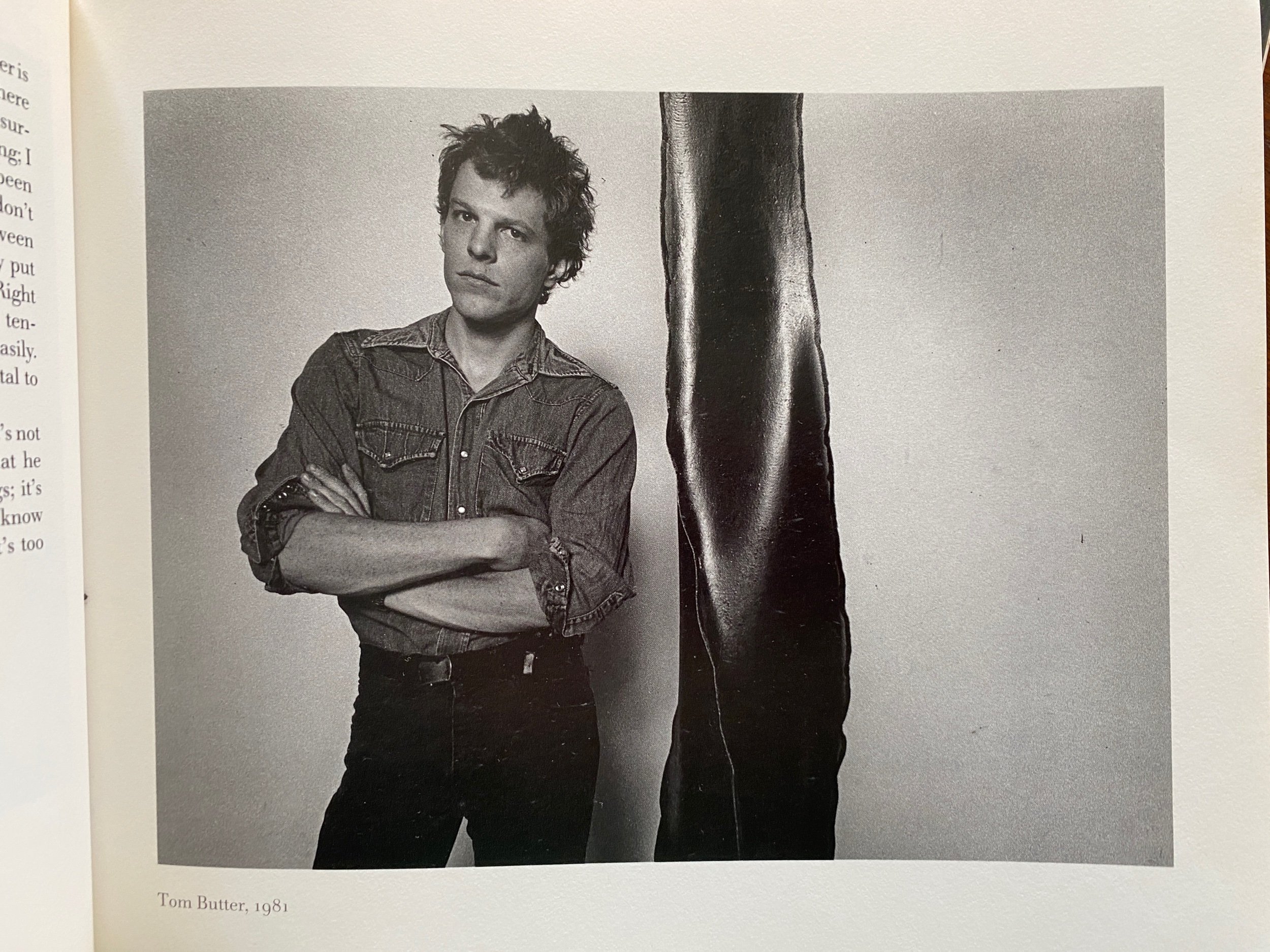

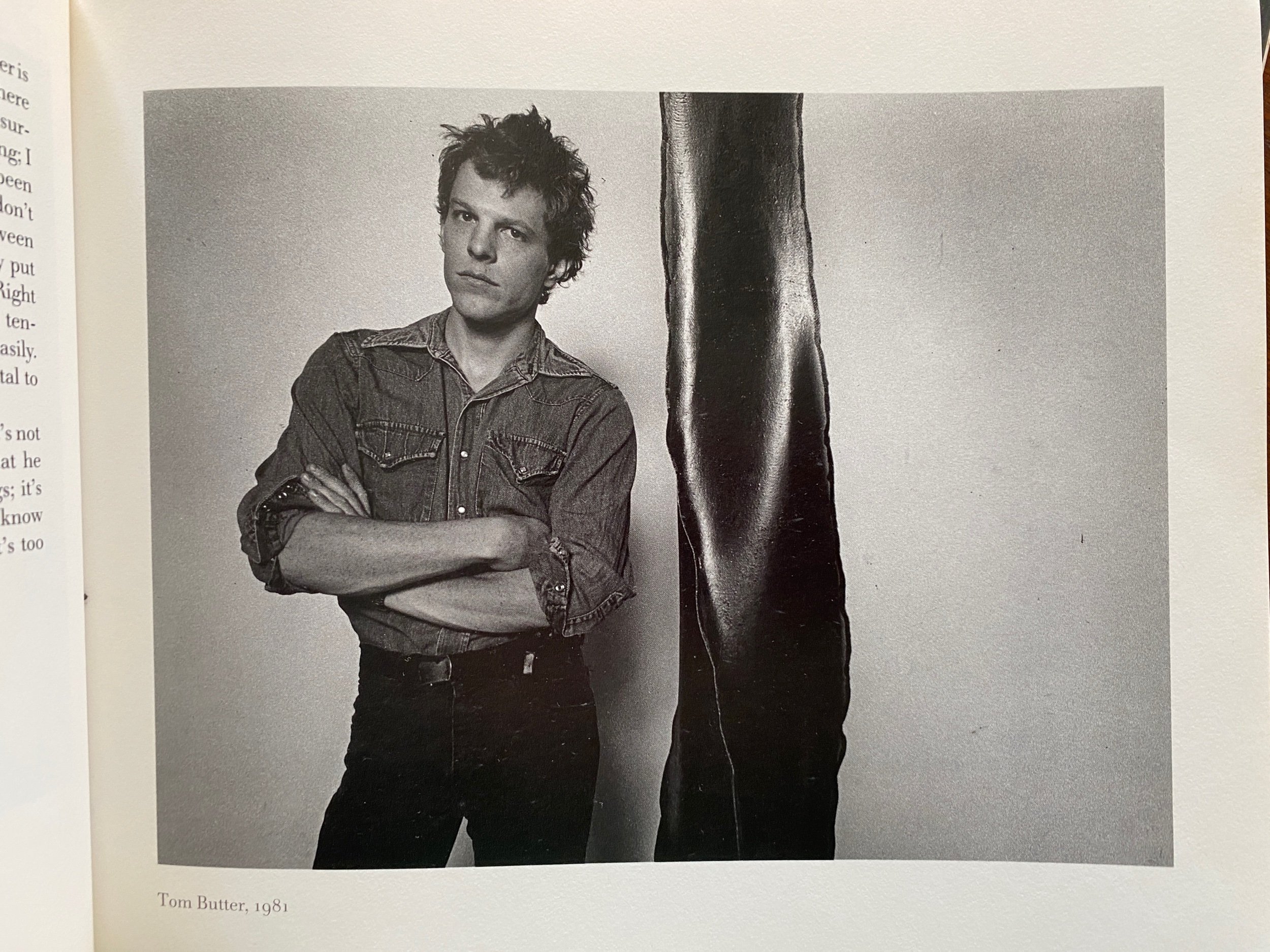

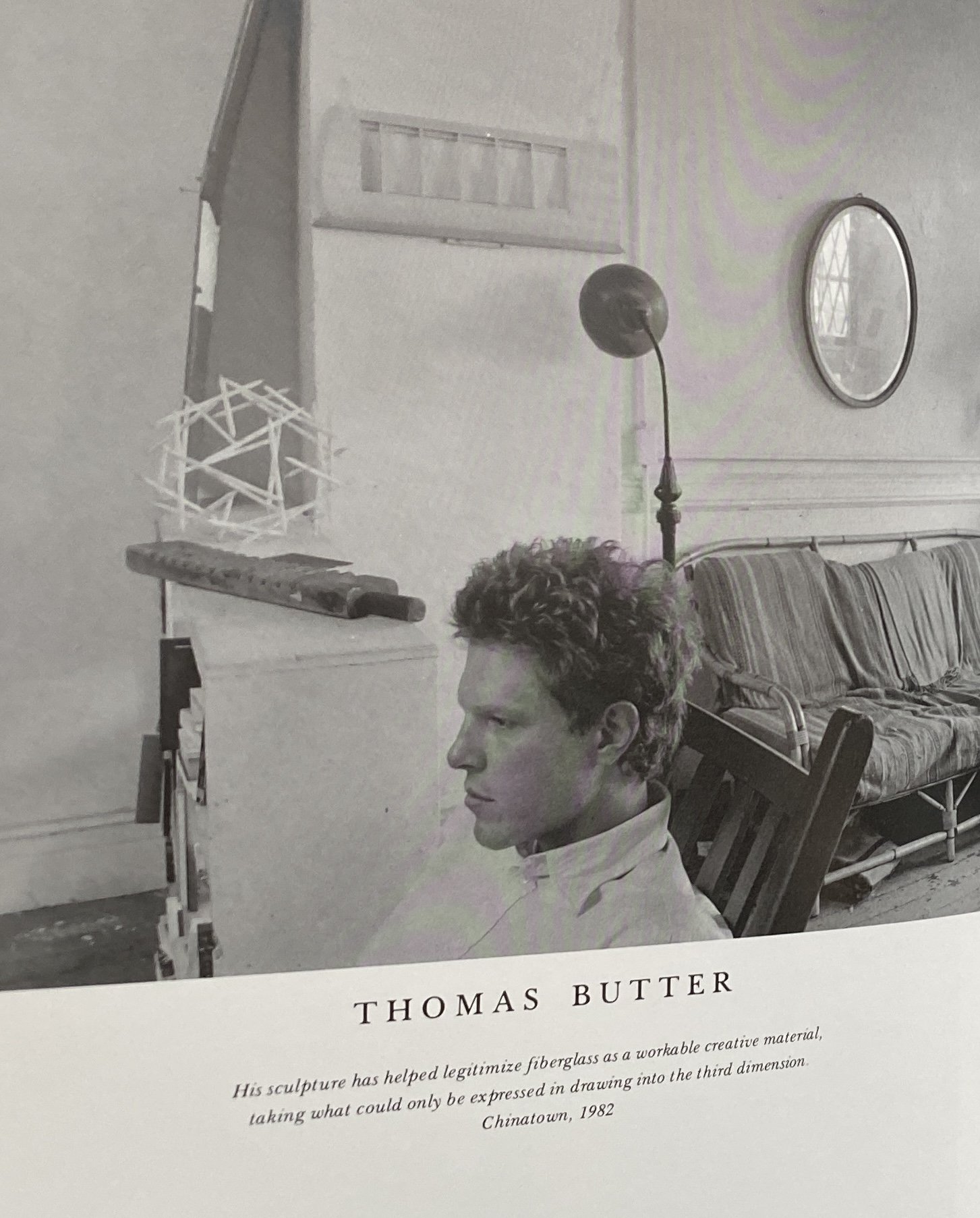

Harvey Stein, Artists Observed, (Harry N Abrams: 1986) p. 36-7

W.H./M.M.D., 1983, fiberglass and resin, 16’ high (4.87 meters), Hammarskjold Plaza Sculpture Garden, Second avenue at 47th St., New York City (photo: Peter Bellamy)

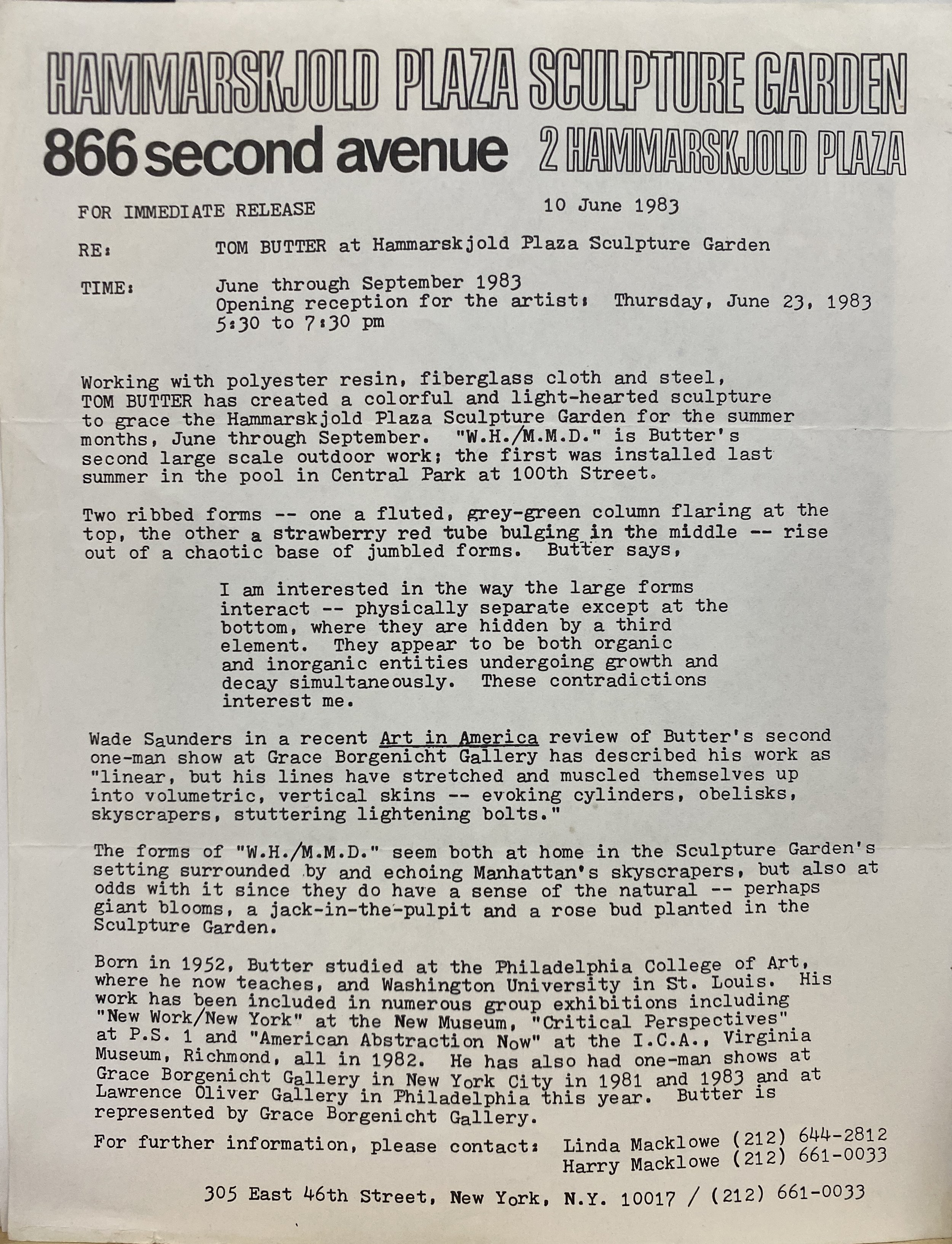

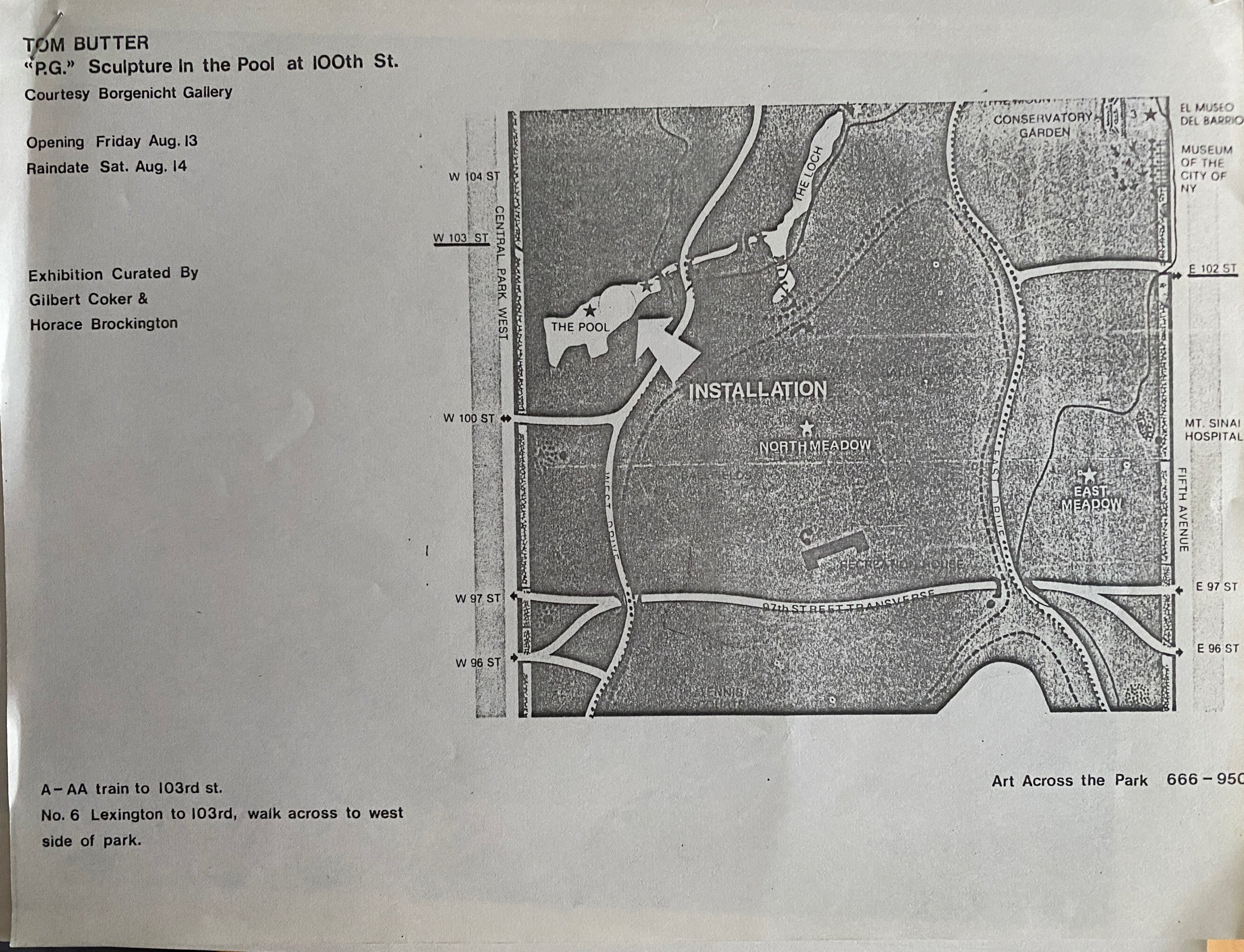

Cryptically titled W.H./M.M.D., this three-part sculpture is Tom Butter’s second large scale, public, outdoor work, and his first in a wholly urban setting (the other was installed last summer in the sylvan pool in Central Park at 100th Street). Made of polyester resin, fiberglass cloth, and steel, it is a narrow organic structure in which irregular translucent forms play contrapuntally with the rectilinear environment of steel and glass. Two opposing vertical elements -one melon-colored, the other gray green - appear to be rising from a dark gray base of curving, inflated forms.

W.H./M.M.D., 1983, fiberglass and resin, 11 x 12 x 8.5 feet (3.35 x 3.65 x 2.59 meters), Hammarskjold Plaza Sculpture Garden, Second avenue at 47th St., New York City (photo: courtesy of the artist)

The first element bulges at its middle while the second bears a trumpetlike flare at its top. One is ungainly, the other is elegant; one warm hued, the other cool. Narrow seaming inflects the flared column, while the other is broad in striation. The irregular ground forms, often punched and riddled with dents, look like some heap of rubbish, yet enclose the vertical members with encircling, even enfolding gestures. Below them lies a dark gray wooden base, as if in mimicry of a sculpture pedestal.

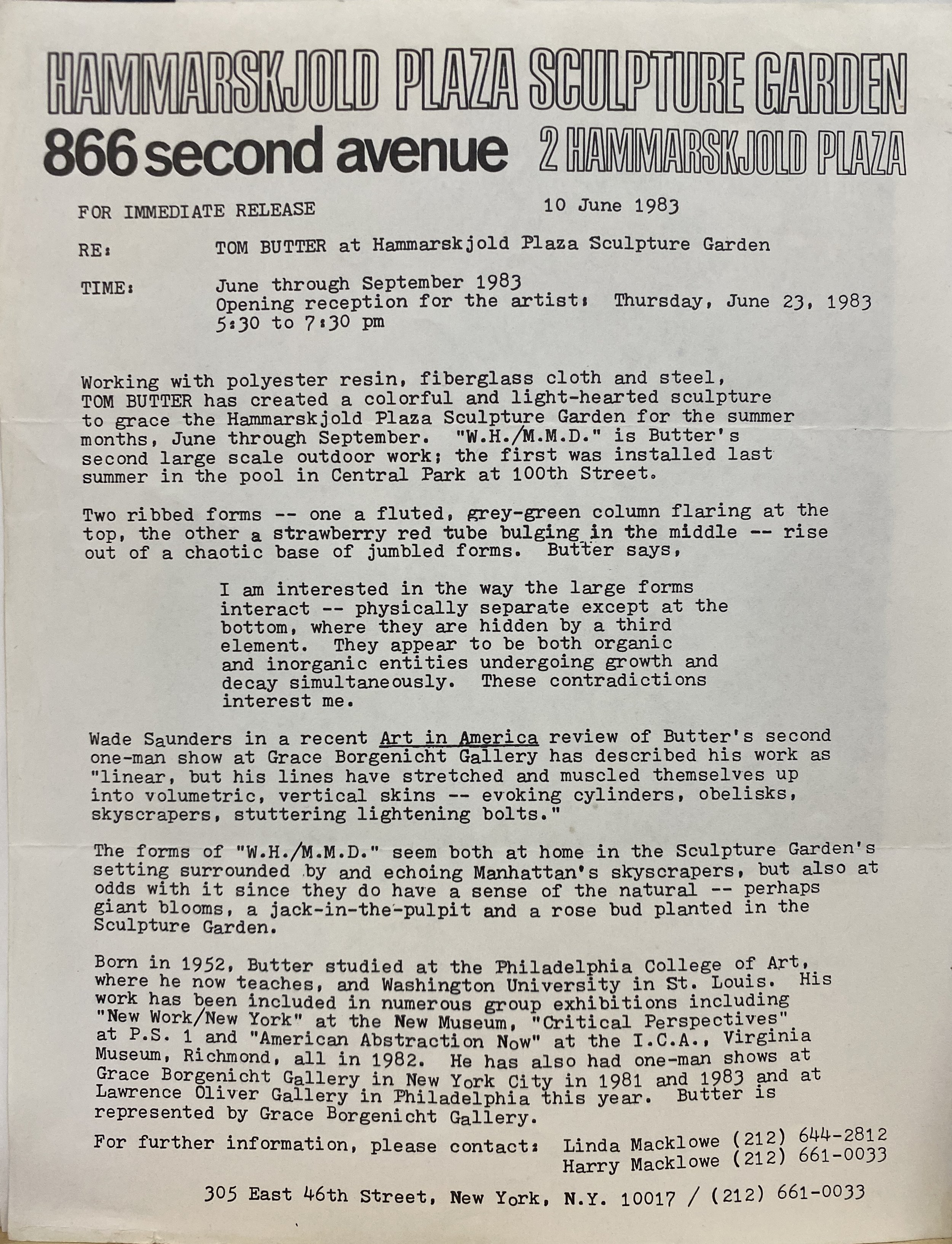

For Immediate Release, Tom Butter at Hammarskjold Plaza Sculpture Garden, June through September 1983

In this work Butter seems to mimic many terms conventional to public art. The sculpture is places smack in the middle of the plaza, in perfect ‘pedestal position’ exactly where you’d expect a Henry Moore, in fact. Moreover, although it has a base, the conventional metaphor for meaning, it is without direct content, modeled on the monument, the sculpture subverts its connotations. Butter’s strategy consists in placing familiar elements in unfamiliar configurations, adding ambiguity to a field known for dependency on publicly recognizable forms. the organic shapes, curved and irregular, work against the rigid grid of the skyscrapers, playing unfixity against fixity of meaning and with it, unfixity of function. The work’s why and wherefore remain unknowable: these are fugitive forms, eluding precise definition; they are endlessly evocative, but evade the closure of meaning. In the appear made on the viewer to reject conventional responses, this allusive and highly equivocal work has important public power.

Kate Linker, Artforum, November 1983, p. 76

One of the more successful outdoor sculptures this summer season. is Tom Butter’s “W.H.-M.M.D.”, at the Hammarskjold Plaza Sculpture Garden, 866 Second Avenue, through September. The scale of the work is right, and the interaction between the organic and architectural shapes and vertical ahd horizontal movements make the work a forceful point of orientation for the trees and buildings around it.

The polyester resin, fiberglass cloth and steel sculpture consists primarily of two vertical forms, each around 12 feet high. One is a thin, fluted, grey-green column flaring at the top. ·Alongside it is something of a cross between an over-ripe tropical plant and a tube swollen in the middle. While the-columnar form reaches upwards, like an offering to the architecture and sky, the strawberry red tube-like form squeezes the movement laterally, turning the sculpture towards the horizontals of the streets.

Reinforcing the tension between manmade and organic growth and decay, are perhaps 50 smaller objects - something of a cross between the peels of a monstrous fruit and scraps of industrial waste - squirming about at the foot of the work. What are these forms? What is happening· -here? The tension is heightened by the light. When the sun is behind the viewer, the sculpture seems solid, expansive, secure. When the sculpture is between the viewer and the sun, the fiberglass becomes translucent. _Now, however, the sculpture seems fragile, as if an angry pin would be enough to turn the sculpture into a pile of waste.

-Michael Brenson, In the Arts: Critics Choice, The New York Times, August 21, 1983

Peter Bellamy, The Artist Project, Portraits of the Real Art World / New York Artists, 1981-1991, (IN Publishing: 1991), p. 162

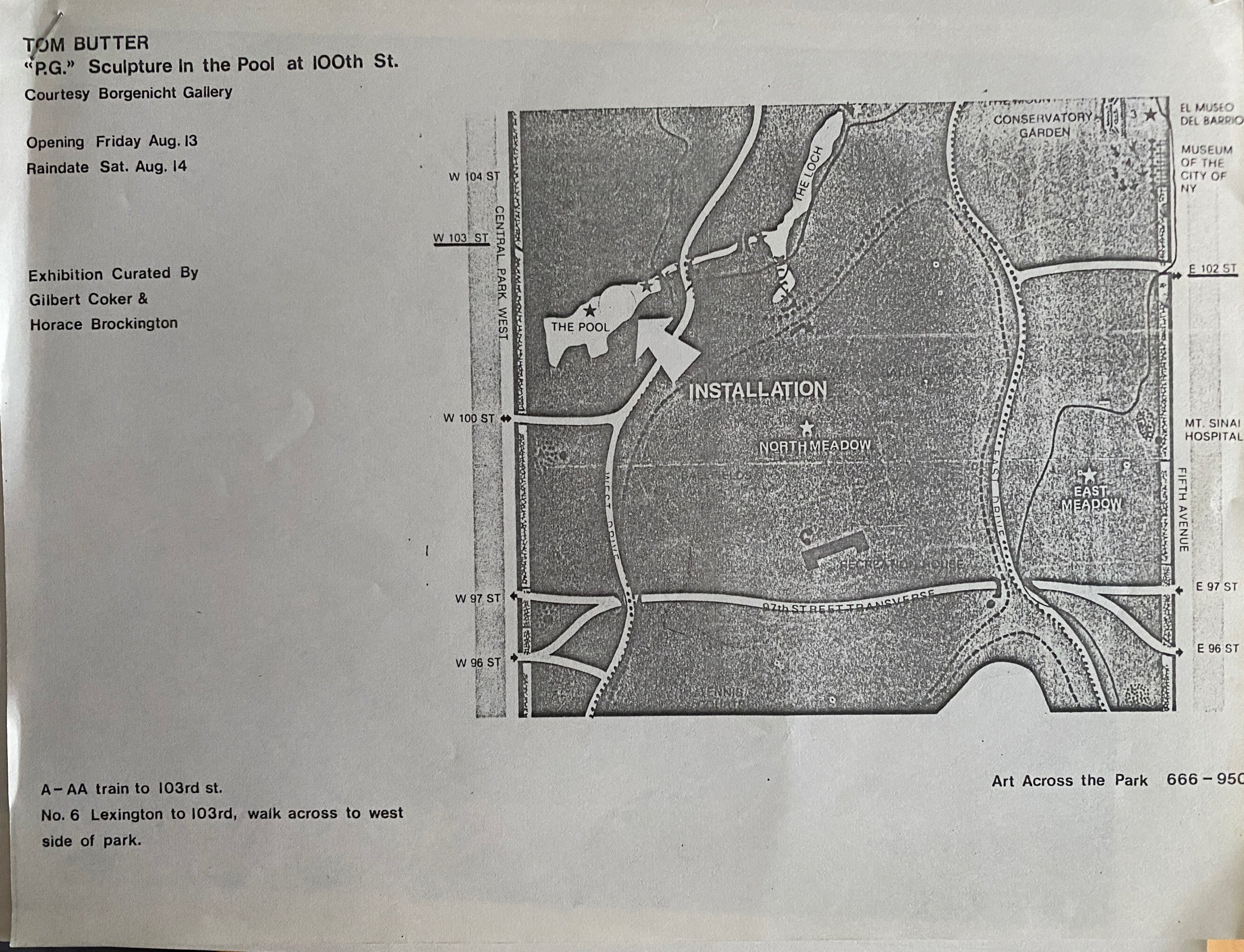

P.G., 1982, fiberglass and resin, Sylvan Pool, Central Park at 100th Street, New York City

Press release, Sculpture in the Pool st 100th St., curated by Gilbert Coker & Horace Brockington

Fleece (1987), polyester resin, pigment, steel mesh, 73 x 23 x 45 inches (1.8 x .5 x 1.09 m)

Fleece (2000’s), polyester resin, pigment, steel mesh 73 x 23 x 45 inches (1.8 x .5 x 1.09 m)

Stroll in the Woods (2000), fiberglass resin, pigment, wood and steel, 37 x 51 x 24 inches (93 x 120 x 60 cm)

detail, Stroll in the Woods (2000), fiberglass resin, pigment, wood and steel

Fits and Starts (2000), steel, fiberglass, pigmented resin, plexiglass, 28 x 31 x 13 inches (71 x 78 x 33 cm)

detail, Fits and Starts (2000), steel, fiberglass, pigmented resin, plexiglass, 28 x 31 x 13 inches (71 x 78 x 33 cm)

Vector (1999), steel, fiberglass, pigmented resin, and wood, 25 x 23 x 20 inches (65.3 x 58.4 x 50.8 cm)

detail, Vector (1999), steel, fiberglass, pigmented resin, and wood, 25 x 23 x 20 inches (65.3 x 58.4 x 50.8 cm)

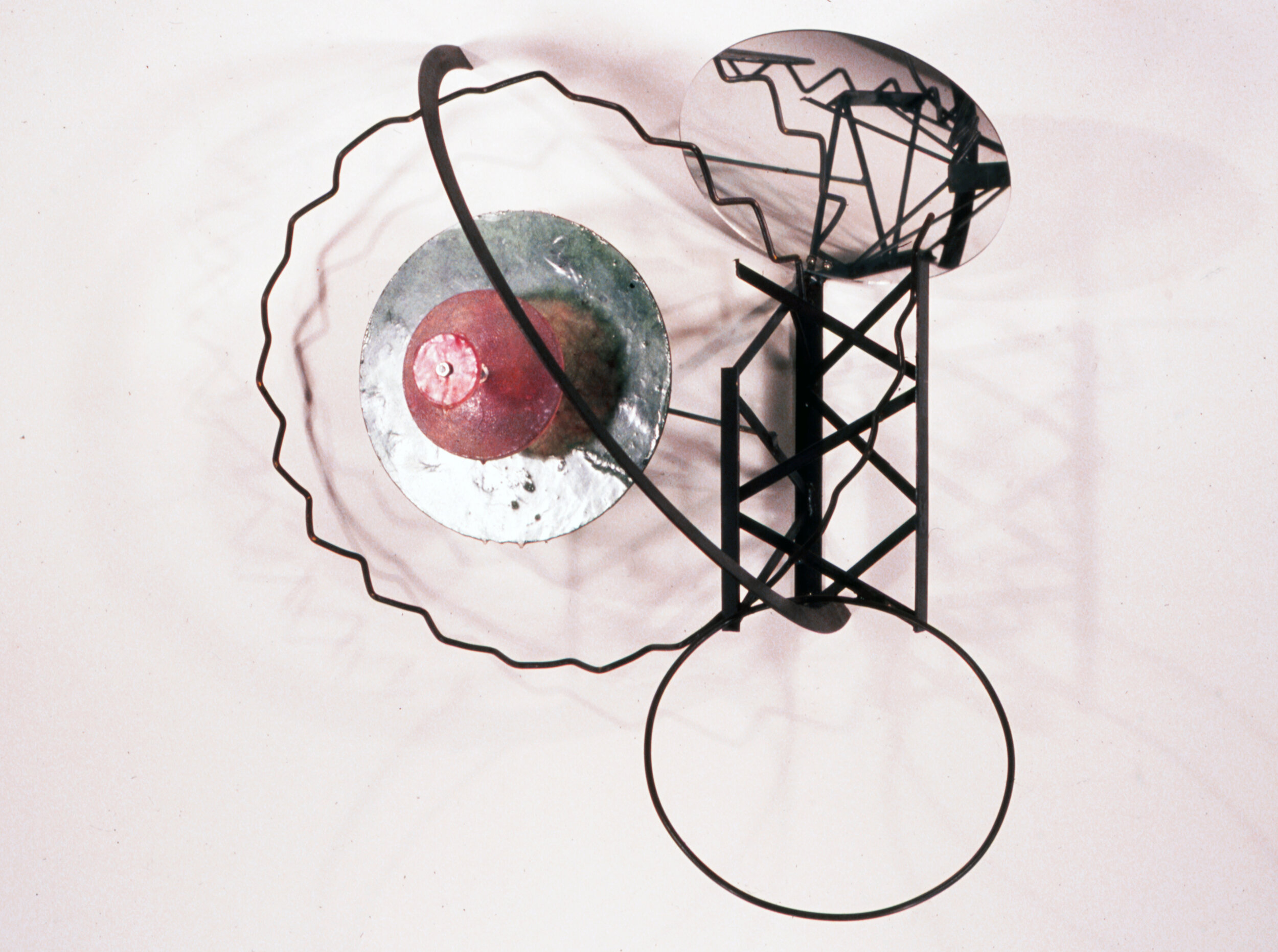

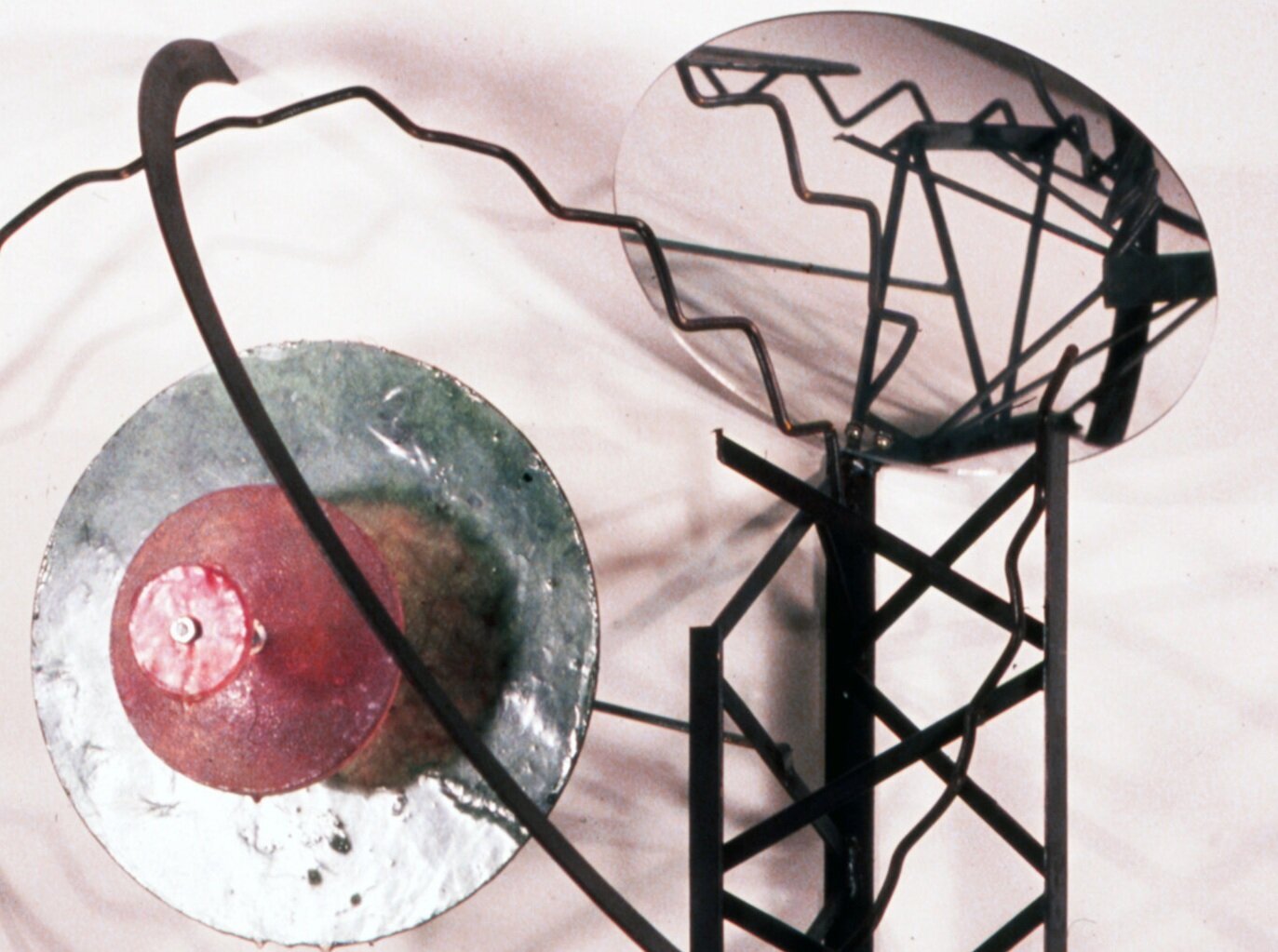

Discs and Hoops (1999), steel, fiberglass, pigmented resin, and plexiglass, 30 x 28 x 14 inches (76.2 x 71.1 x 35.5 cm)

detail, Discs and Hoops (1999), steel, fiberglass, pigmented resin, and plexiglass, 30 x 28 x 14 inches (76.2 x 71.1 x 35.5 cm)

BOAT SEA, fiberglass and steel with wood, freestanding sculpture: 6 feet high, three feet wide, 2 feet deep

BOAT SEA detail

FOOTBRIDGE, polyester resin on steel with old shoe, freestanding sculpture: 8 feet long, 3 feet high, two feet wide

DRYDOCK, freestanding sculpture: 5 feet high, 4 feet in diameter

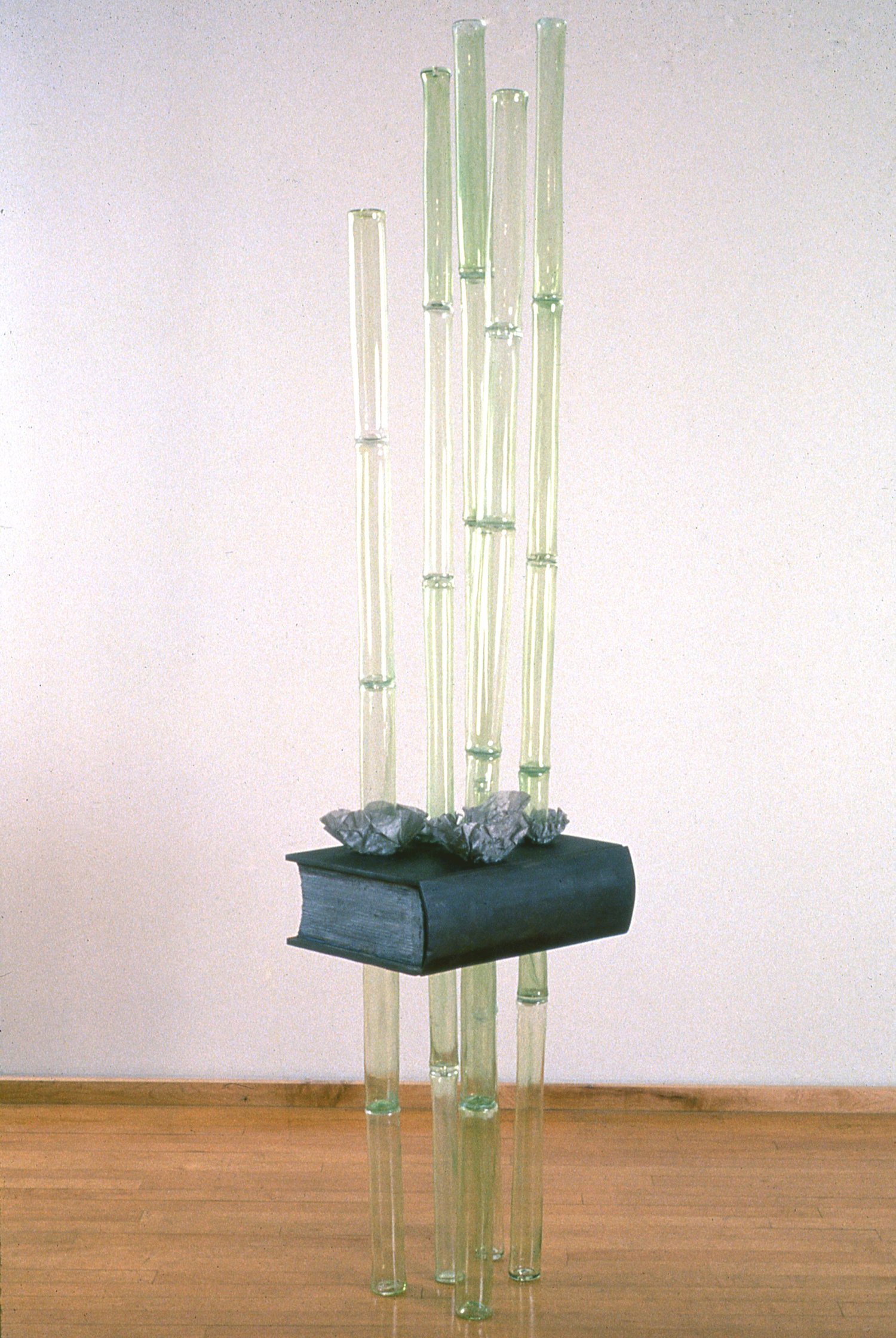

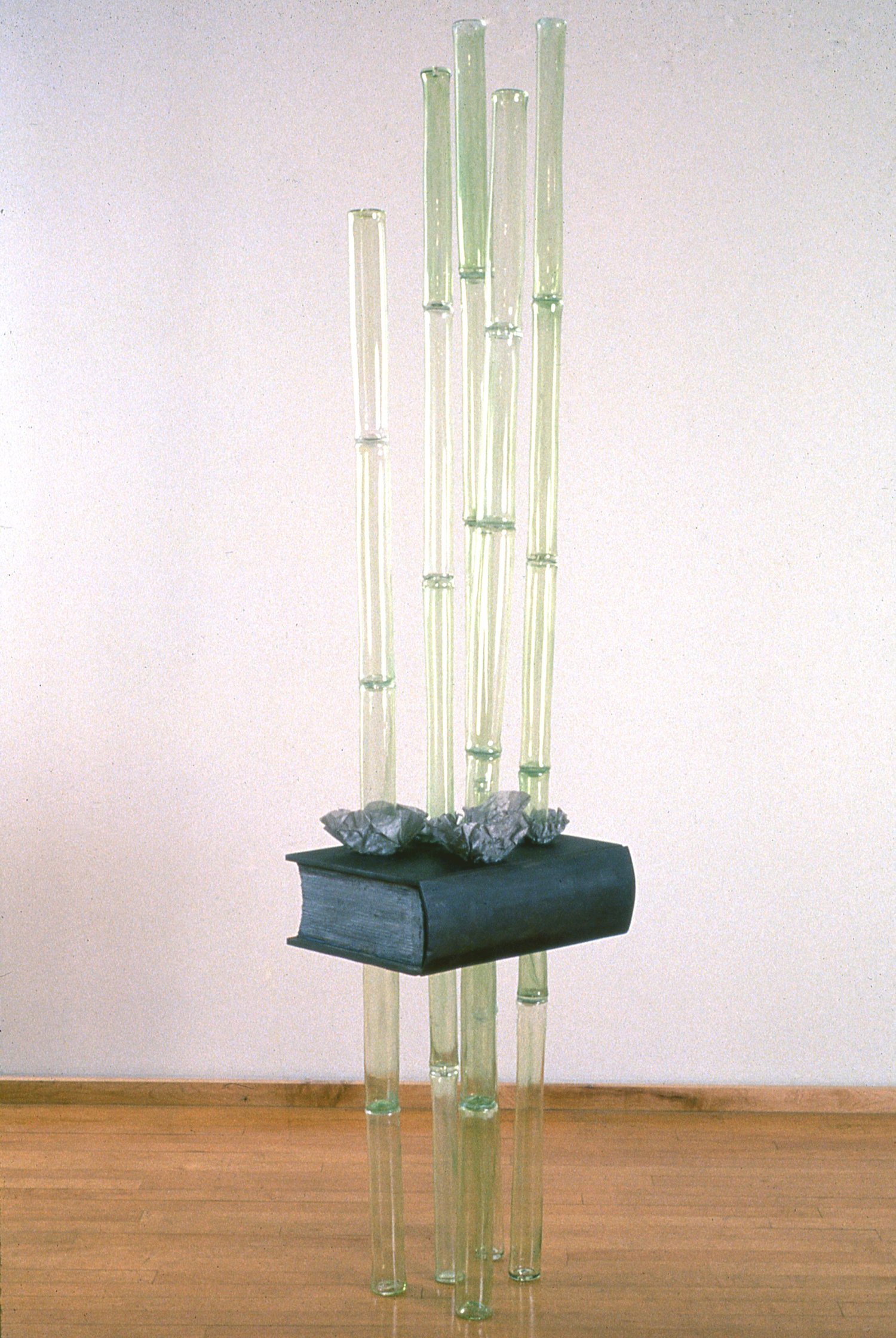

GROVE (1995), glass, wood, graphite, freestanding sculpture: 56 inches high, 22 inches wide, 26 inches deep

BEING CLOSE (2019), installation view, Aidron Duckworth Art Museum, Meriden NH

BEING CLOSE (2019), detail of the wheel. Pigmented cement board and steel truss connected to a tree for lateral stability. Turning this wheel sents the book into the field.

BEING CLOSE (2019) detail of the truss. Spanning fifty linear feet, an equilateral truss (measures nine inches and comes apart in five 10’ sections) with a gear on either end, supports a length of chain to move a book. Three pairs of legs support the truss. .

BEING CLOSE (2019), detail of the book.

Host (2018), steel with motor, backer rod, foot pedal and timer, freestanding kinetic sculpture: 15 feet tall, variable 6 foot diameter pile unspools at base

Host (2018), detail, one of six backer rod spools, steel with motor, foot pedal and timer, freestanding kinetic sculpture: 15 feet tall, variable 6 foot diameter pile unspools at base

Rope Trick (2016), 78” l x 28”w x 36”h, steel with motor, hauzer, foot pedal and timer, freestanding kinetic sculpture

Working (2016), string, gloves and steel, foot pedal motor and timer, freestanding sculpture: 54 inches high, spinning 30” radius

Dervish (2016), stainless mesh and steel, foot pedal and motor, freestanding sculpture: height 7 foot 6 inches, 5 foot diameter

Watching (2014), 24’l 12’w x 12’h, steel with motor, vinyl, foot pedal and timer, freestanding kinetic sculpture

Set (2014), synthetic polymer resin, pigment, c clamps and steel, 40 x 80 x 160 inches (1 x 1.5 x 4 m)

Set (2014), detail of two discs grazing the floor, pigmented resin, c clamps and steel, 40 x 80 x 160 inches (1 x 1.5 x 4 m)

Lampshade (2000), resin, pigment, steel, concrete and boots

Lampshade (2000), detail - second form suspended within, pigmented resin, steel, concrete and boots

S Machine (2007), tutu fabric, steel, wood

A few feet away, “S. Machine,” another hollow steel truss, flirts with other modalities. It is lightly stuffed with a pink gauzy material evoking the feminine; dangling one third of the way from the top are wooden orbs suggestive of buoys, flotation devices, or (again) breasts. Although not literally kinetic, the piece has movement: the frothy synthetic fabric seems both to spill out of and be trapped by the girded column. The effect is one of abiding dichotomies—linear and curved, steely and gossamer, “masculine” and “feminine”—that defy resolution.

S Machine (2007), detail of the materials in use: pink tutu fabric stuffed into the steel with carved poplar painted white

The show rewards viewing from different angles—close scrutiny of the pieces’ materials and nuances of movement—and a consideration of the pieces in relation to each other. Ultimately, one notices that Butter’s works create provisional scenarios and spaces—scenes one might hope to enter and explore—and moments of rest. They alternately invite and disrupt a sense of ease and stability—pulling the viewer in only to stymy expectations that become apparent by being thwarted. Viewed together, Butter’s sculptures and paintings embody a dialogue about the tensions between stillness and movement, 2-D and 3-D, with each piece contributing a motive energy of its own. The invitation to participate proves difficult to resist—upon leaving the show, this viewer realized that she had served as a willing and engaged foil in an ongoing exploration of disequilibrium. - Mara Dale, “Astir” Whitehot Magazine, December 2015

Strange Brew (2006), resin, pigment, steel, thread

Strange Brew (2006), detail of the pivot point, pigmented resin, pigment, steel

Levity (1998), synthetic polymer resin, pigment and wood

detail, Levity (1998), synthetic polymer resin, pigment and wood

Monk (2006), resin, pigment, steel

Procession, resin, pigment, wood, steel

detail, Procession (2000), resin, pigment, steel, wood

Necklace (2003), resin, pigment, wood, steel, 54 x 12 x 72 inches (1.3 x .3 x 1.8 m)

detail, Necklace (2003), resin, pigment, wood, steel, 54 x 12 x 72 inches (1.3 x .3 x 1.8 m)

Drinking Drunk (2000), steel, wood

You must always be intoxicated. It is the key to all: the one question. In order not to feel the horrible burden of Time breaking your back and bending you toward the earth, you must become drunk, without truce. But on what? On wine, poetry or virtue, as you wish. Bur you must get drunk.

detail, Drinking Drunk (2000), steel, wood

And if at times, on the steps of a palace, on the green grass of a ditch, in the mournful solitude of your room, you awaken, and your intoxication is already diminished or gone, ask the wind, the wave, the star, the bird, the clock, everything that flees, everything that groans, everything that rolls, that sings, that speaks, ask what time it is: and the wind, the wave, the star, the bird, the clock will answer you: ‘it is time to get intoxicated! Become intoxicated! On wine, on poetry, or on virtue, as you will.’ -Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867), ‘On Intoxication’, Spleen of Paris, (ed. Dover: 1992)

Still Life (1999), steel, stone, wood, wire, resin

Mask (2007), resin, pigment, steel

detail, Mask (2007), resin, pigment, steel

Belly (2007), polyester resin, pigment, steel

detail, Belly (2007), polyester resin, pigment, steel

Stand Off (2000), polyester resin, pigment, steel

Barn (1996), polyester resin, pigment, steel, 56 x 59 x 24 inches (1.4 x 1.5 x .1 meters)

Big Wheel (1997), polyester resin, steel, 74 x 74 x 29 in (1.8 x 1.8 x .73 m)

‘Big Wheel also reflects Butter’s Interest in childhood play. A large, thin disc of translucent pink fiberglass is mounted on an axle supported by armatures; just over six feel tall, the construct suggests a delusionary mixture of Ferris wheel, erector set, and half-cucked pink lollipop. At the same time, the disc’s jagged edges recall the sawmill blades that used to be stock terror devices in silent-film suspense serial. Indeed, the works do concern themselves with suspense – not in terms of narrative, but physics.’ Justin Spring, “Tom Butter, Curt Marcus Gallery” in Reviews, Artforum MAY 1998 ( p. 148-9)

Eclipse (2000), polyester resin, pigment and steel, 93 x 50 x 44 inches (2.3 x 1.2 x 1.1 m)

detail, Eclipse (2000), polyester resin, pigment and steel, 93 x 50 x 44 inches (2.3 x 1.2 x 1.1 m)

Forge, 1996, leather, polyester resin, pigment, steel

His mixed-media sculpture conjures up images of old technological optimism only to undercut this optimism with other, less congenial images. He uses modern materials - fiberglass is a favorite - but gives these materials narrative meaning outside technology. In two pieces, ‘Metropolis’ and ‘Forge’, hands in the form of real gloves stiffened with resin crank away on big wrenches or grasp massive chains. These are big, impressive pieces that seem symbolic and bluntly formal at once. The symbols are clear enough.

The gloves suggest the heroic proletariat and the idealism of socialist labor. Like cutouts from a 1920’s Soviet poster, they suggest worker power and potential for social justice. But it isn’t long before we progress from optimism to futility. The gloves rapidly become absurd, disembodied things, extensions of invisible workers who perform their tasks in ignorance. In the simplest terms, they are symbols for alienation, nothing more. In ‘Forge’ for example, the hands seem to be pouring a length of chair from what looks like an enlarged flower petal vase into an ordinary galvanized bucket. A surrealistic trick? Not really. -Richard Huntington, “Technology, geometry and skepticism” in The Buffalo News, Tuesday February 18, 1992

Metropolis, 1992, leather, wood, graphite, steel

Butter makes metaphors - even potentially humorous ones - seem more like hard facts. The ideas he presents may be ambiguous and contradictory, but the form is not. Finally, the work may be a kind of critique of metaphor as much as a commentary on the downside of technological society. With Butter there isn’t a tinge of Chaplinesque redemption in evidence anywhere. He holds in check the potential humor of, say, a wrench hopelessly yanking on a chain welded to a floor plate.

This is no extravagant surrealistic leap the the illogical. In fact, Butter studiously avoids the standard surreal dream atmosphere by giving his strange chain pourer a flatly factual presence. The act may be absurd, but the action is believable. Butter carefully balances message and form. Form is made to tell the tale trimly, with no excessiveness, nothing overstated. The sculptures are studies in economical form, and they are pretty to look at as well. Sometimes Butter is careful and neat in his merger of idea and form. It seems to time that to look at these sculptures as formal abstractions is little more than an add-on experience. The major point has already been made, pack there with those chains and gloves. Still, these sculptures have conviction. Tom Butter is among the skeptical.

S. L.. 1982, fiberglass and resin, 84 inches high, at Grace Borgenicht

Modern sculpture is roughly divisible into open, horizontal, linear/planar constructions and closed, vertical, solid seeming monoliths. Most constructions are abstract; most monoliths are figurative or biomorphic in character. Tom Butter’s sculpture straddles this opposition: his constructivism limns a nature rampant. His pieces are at core linear, but his lines have stretched and muscled themselves up into volumetric, vertical skins evoking cylinders, obelisks, skyscrapers, stuttering lightning bolts - five to ten feet high. His lines and so his sculptures are imbued with expansion and growth; although his constructions are traditionally composed and seemingly complete, they suggest continuation or extension. They have gained the pulse we often sense in monoliths.

M.R. 1984, Fiberglass and resin, 99 x 9 x 11 inches

Butter cuts, suspends, guys and staples pieces of fiberglass cloth together to make his skinny volumes, which he then freezes with catalyzed polyester resin colored with dyes. His approach permits him almost to ignore gravity while working: the bottom of an element doesn’t have to support the top physically until the resin has hardened, at this time its weight is no problem. Butter generally assembles his sculptures from these premade parts, though he will sometimes shape cloth around a rigid fiberglass element that he has made earlier - the work N.B. for example. Within a single sculpture, similar shapes are similarly colored.

Artist in the studio with M.R., New York City, 1984

Butter is probably attracted to the resin/cloth combination for the reasons other sculptors have been: fiberglass is relatively simple to master, requires little equipment to work, can produce objects both light and extremely strong, is responsive to touch, can be ambiguously translucent, and seems to possess a surface simultaneously wet and dry. For Butter is is also a material which can be worked quickly and gesturally - in which his loose personal geometry doesn’t look sloppy.

L.J., 1984, fiberglass and cloth, 101 x 22 x 11 inches

Quickness - actual and apparent - is central to Butter’s sculpture. Since he can readily make and rapidly deploy almost any volume he conceives, he recovers some of the liveliness that was central to Chamberlain’s and Sugarman’s great sculptures of the early 1960s. Although the springiness, even timidity of his forms is suggestive of growing things, it is the relationships in which he places his basically abstract parts that prompt and sustain a biological reading.

T.T., 1984, fiberglass cloth and polyester resin, 92 x 56 x 18 inches

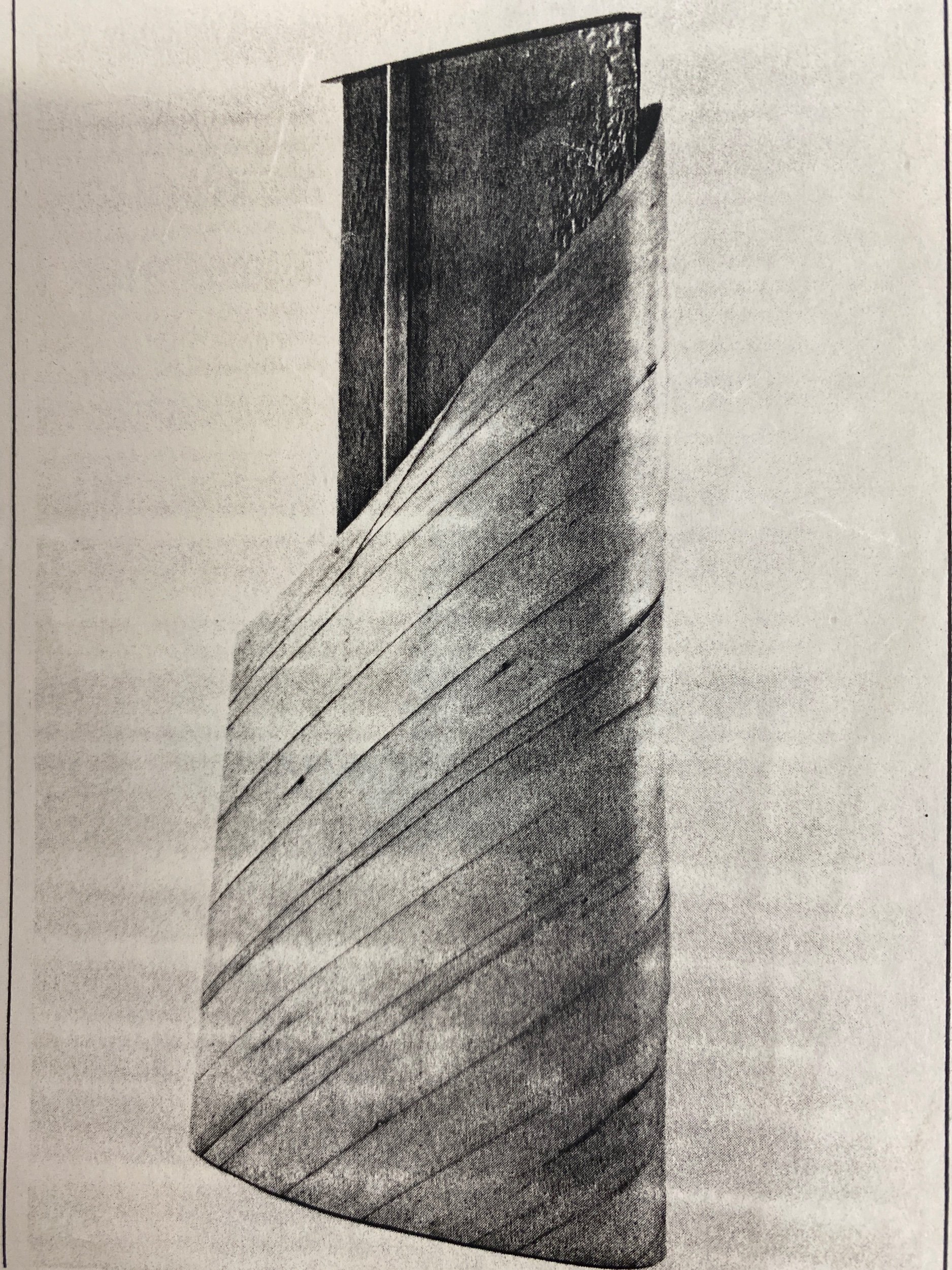

With a couple of exceptions, the sculptures play a twisting, upward movement off a still, vertical core - actual or implied - like a vine twining around a tree, though in the sculpture the elements are structurally interdependent.

T.T., 1984, fiberglass cloth and polyester resin, 92 x 56 x 18 inches

Such a movement brings with it a suggestion of time: the pieces are ongoing, not fixed. In W. H. a swollen, red, ten-sided column, its greatest girth near our eye-level, rises up from a tight circle of dark, collapsed arcs, like a shucked ear of corn surrounded by husks. Though large, its translucency keeps the piece light; it finesses the big, bigger, biggest quality of monoliths.

D.H., 1985, fiberglass cloth and resin, 32 x 12 x 12 inches (ed.5)

Butter’s shapes aren’t unique - Noguchi’s akari lamps, Eva Hesse’s, John Duff’s, and Barbara Zucker’s sculptures are acknowledged sources - but his active handling of space is fresh. He plays the perceived hollowness of his elements of against the open enclosure of their arrangements to suggest separate but simultaneous presents.

C.B., 1983, fiberglass and resin, 6’ tall

S.L., 1982, fiberglass and resin, 82” tall

In S.L. and C.B. (his titles are people’s initials) he partially revives the stunning spatial richness and ambiguity that Constructivist-derived sculpture once had. -Wade Saunders, “Tom Butter at Grace Borgenicht”, Art in America, April 1983, p. 117

A.K., 1984, fiberglass and resin, 92 x 18 x 18 inches

Solid sculpture embodies the traditional function of the medium as a way to create and organize volumes. Some 20th-century sculpture. however, like that of the constructivists. emphasizes structure rather than mass. In structural sculpture the spatial envelope is often implied rather than directly represented by material: the skeleton of the piece takes precedence over mass and surface. Tom Butter's sculpture falls somewhere between these extremes. Butter's pieces flaunt their structure. but they also emphasize ~he qualities of their integuments, of the skins that make them volumetric.

Butter's sculptures. 'fabricated of resin-impregnated fiberglass · cloth, are light but rigid and usually translucent. Their skins are also, in a sense, their bones for every element or every piece is formed from the plasticized screening. Aside from the properties ' already mentioned. however, we also note in both collections two other salient characteristics of this sculpture: It is energized by light and color and it is suggestively tactile, so much so that the material creates an illusion of improbability.

Thus every element is hollow. Formed or "skin " shaped into bars. slabs, ‘ovoids’ and other configurations. So while the sculptures dis place volume. or else articulate it. they also enclose it within their individual components.

There's an intrinsic freedom to this kind of sculpture: one senses that the material's potential to describe. evoke and fantasize is limitless. for nothing about the forms is ordained by the material used to shape them. Furthermore, the pliable fiberglass is a more "friendly" medium than a resistant one like stone. end less liable to fracture . There's no tension In it: the material yields totally to the artist's whim.

T.C.B., 1984, fiberglass and resin, 10” tall x 14” wide

The white ones looks like gelatin or ice; they project on one hand softness and airiness and on the other coldness. In either case the surfaces are delicious; because the colors are part of the material, they are resonant rather than simply reflective.

T.C.B., M.R., A.K., 1985, fiberglass and resin, color and dimensions variable

Each show contains seven pieces. Some at the Morris Gallery are ribbed, making the skin-bones contrast more pronounced. Others are vaguely biomorphic: one looks like an exotic strand of purple kelp.

A.K., 1984, fiberglass and resin, 7’8” tall

Still others employ a "hairpin" element that forms the basis of the extrapolations at Lawrence Oliver. The "hairpin" form used as legs, or stacked. or joined with a lozenge form - becomes in both collections symbolic of the melding of surface and support.

-Edward J. Sozanski, Art combining different ideas about sculpture, The Philadelphia Inquirer, ~THE ARTS Thursday, November 21. 1985

Catapult, 1993, wood, graphite, wire thread, 27 x 81 x 120 inches

Tom Butter’s sculptures of the late ‘70’s and early ‘80’s, eccentric abstractions related to work by John Duff and Eva Hesse, were made of fiberglass. But fiberglass, like abstraction itself, turned out to have problems – indeed, physical hazards. Butter reduced his use of the material and began to put it at arms length (sometimes quite literally) as wood, metal and various kinds of manufactured objects, including work gloves, found their way into his work.

In The Balance II, 1993, 80 x 120 x 11 inches

One of the strongest sculptures in this recent show, In The Balance II, measures a stack of ruffled wire-mesh disks against a large, upright fiberglass plate whose shape and position suggest a gong, except that is vibrates with light rather than sound. The disks and the plate appear at either end of a slender metal arm supported by a vertical column; a wire-wrapped ball marks the intersection. Palming this ball from above is a stiffened leather work glove – the had of an unseen deity (or an artist?) tipping the scale. As a metaphor for Process Art, this is funny, deft, and unabashedly corny.

Silver Lining / Five Days Without Water, 1993, fiberglass, steel, resin

Fiberglass appears in the works in other ways that make it seem a stand-in for art itself, difficult to handle and resistant to interpretation. In Silver Lining / Five Days Without Water, oversize fiberglass petals sprout from the top of a quasi-figurative metal totem as if from a mad Easter bonnet. At the risk of a little absurdity, Butter is engaging a range of altogether serious issues, of which form and process are only the beginning. In Figure of Speech it shows up as a kind of deflated bladder, a vestigial organ tethered to an attenuated support by a snaking arcing length of iron chain.

Hand to Hand, 1993, fiberglass, resin steel, and leather gloves

Another equally radical form of bodily dissociation is enacted in Hand to Hand, which seems directly descended from Bruce Nauman’s famous Hand to Mouth, except that in Butter’s version the torso is replaced by a rolled piece of wire-threaded fiberglass. Cast-metal work gloves stand in for hands, their cuffs spooled with wire attached to the wall above; this is a puppeteer’s version of the steel-driving art-worker, equal parts Richard Serra and Wizard of Oz.

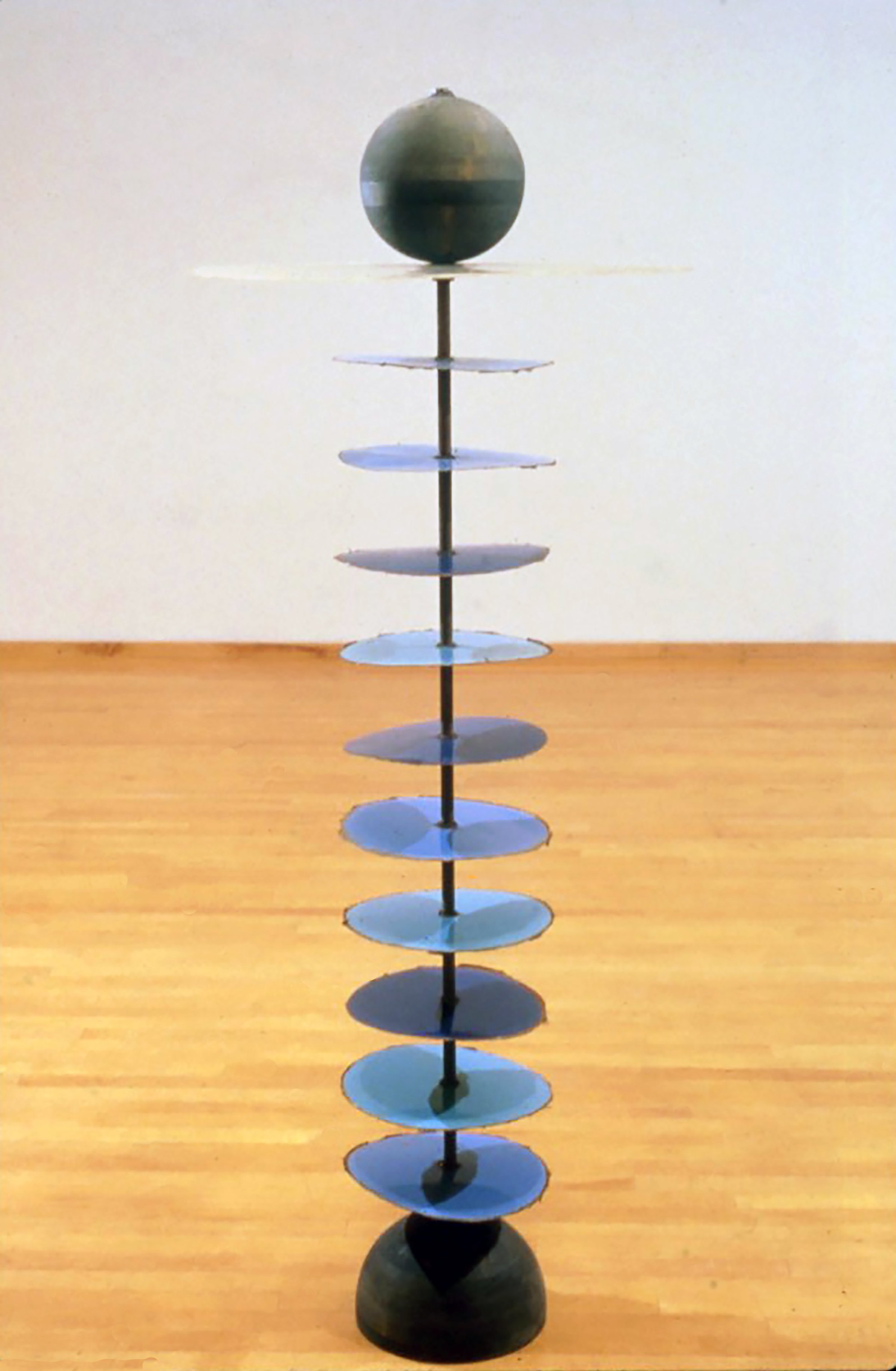

Head Spin, 1993, fiberglass resin, steel and wood

In Head Spin, a series of metal disks strung along a human-sized metal spine is topped with a large fiberglass plate that proffers a featureless wooden head as if it were John the Baptist’s on Salome’s platter.

Catapult, 1993, wood, graphite, wire thread, 27 x 81 x 120 inches

Catapult brings a ghoulish slant to the question of gravity and ways of escaping it. Resting on the blade of a long, slender oar is a blackened human skull. A nasty thing ready to be propelled into our faces, this skull is to mortality what the leather glove is to transcendence: a joke, talisman, a place-marker for an unanswered question. Catapult’s staginess is characteristic of Butter’s current work, in which faked equilibrium and disembodied figuration challenge the premises of organic abstraction.

-Nancy Princenthal, ‘Tom Butter at Curt Marcus’, Art in America, December 1993 (p. 98-99)

Night Train, 1998, synthetic polymer resin, pigment, and steel

‘In his recent show, Tom Butter presented eight works described as kinetic sculptures. But their kinesis was amusingly elusive. Only one seemed to earn the name: Night Train (all works 1997), a large steel wheel suspended by a perpendicular column sheathed in fiberglass, revolved just perceptively.

Night Train, 1998, synthetic polymer resin, pigment, and steel

A light touch, however, set the piece into smooth, sure rotation, and it turned out that all but two pieces, Two States and Dive, could be activated by a bit of manipulation (though some has such a limited range that they seemed barely to jiggle).’ -Justin Spring, “Tom Butter, Curt Marcus Gallery” in Reviews, Artforum, May 1998 ( p. 148-9)

Lode, 1986, polyester resin, pigment, steel, 86 x 50 x 34 inches

Tom Butter’s approach to making sculpture has always involved taking chances. These may be procedural, such as testing the limits of how fiberglass flows and, not, its marriage to wood, or conceptual, based on the design of an object. The empirical directness with which he works warrants consideration. Each of his pieces has constructive implications. And to acknowledge this constant forward momentum is to laud the candor and verve with which his recent work is initiated, developed and sustained. Butter has worked with fiberglass since 1979. A malleable material receptive to subtle inflections of touch and color, fiberglass can be cast or molded into various shapes.

Butter has always pushed his abstract work towards ambitious scale and intricate configurations. Earlier pieces such as P.R. and M. W. set a standard for monumental free-standing work that aggressively occupied space and investigated for- mal strategies balanced between rigorous geometry and amorphousness. The severity of their modular shapes and edges was softened by Butter's tendency to anthropomorphize. And the serial regularity with which a motif developed was masked by a quirky, idiosyncratic impulse enlivened by color and a surface that quivered and shimmered-like "skin."

By emphasizing the "organic" potential of fiberglass, Butter's work has an affinity to earlier work by·~a Hesse and Bruce Nauman. A preoccupation with abstract eccentric shapes and natural forms rendered through.an empirical rapport with materials is worth noting here because it ·not only underscores a dominant sensibility in contemporary sculpture but reflects a deeper desire to synthesize formal strategies ness, the work also gains solidity. of a dress - has a rightness on intuitively, but his pieces fight and emotional impact without re- sorting to traditional narrative or figuration. Numerous methods involving diverse media and techniques have achieved this end and explain, at least in part, sculpture's present breadth and vitality.

The marriage of fiberglass and in Butter's recent work signals a significant change. The combination of two different media generally requires an initial period of familiarization, an implicit give-and-take that eventually stabilized in compatibility. Butter’s decision to introduce wood (maple and poplar) has its positive ramifications. Enhanced by new texture, color and openness, the work also gains solidity.

In Lode, for example, the draping of resin-colored fiberglass over, under and through an elliptical poplar frame . delicately studded with brads and bridged in one section by a clear sheet of fiberglass, not only demonstrates dexterity and control (without seeming finicky) but embodies the kind of experimental rigor and imagination that distinguishes the best of Butter’s work.

Lode, 1986, polyester resin, pigment, steel, 86 x 50 x 34 inches

Everything about this piece, its subtle projection of fins beyond the edges of its wooden frame, the rippling furrows of its fiberglass membrane that fan out at the bottom like the tail of some great fish or the hem of a dress, has a rightness on the edge. When Butter pushes the physical extensions of his materials, the results are rewarding. Butter’s wall sculpture pushes in a new direction. Considering its material aspect, a comparison with John Duff’s reliefs is instructional. Whereas Duff’s model is reductive and elegant, Butter’s is exuberant and rough around the edges. For all of their formal acrobatics, surface contortions and twisting, Duffs pieces have a graceful poise at ease on the wall. In spite of their residual signs of process and color activation, these objects achieve a "classical" perfection. Butter also works intuitively, but his pieces fight against perfected decorum, stability and homogeneity. In Hand, for instance, materials collide and slide into each other. Butter seems to accept the paradox of making ‘wall’ sculpture by stressing the tension implicit in this presentation. -Douglas Dreishpoon, “Tom Butter at Curt Marcus: October 4-30”, Arts Magazine, January 1987

In Irons, 1986, fiberglass resin, and maple, 7 feet tall

Some blocks away from that corner, Tom Butter’s sculptures at Curt Marcus neither shone nor glittered. Made of plywood and fiberglass, they need never be polished, an occasional dusting will do. Rather than volumes displacing or carving out space these sculptures are envelopes. A translucent skin is wrapped around an empty core. The space the pieces seem to take up, as opposed to their physical space, has the form of an irregular bubble extending out about a foot from the surface. This bubble seems to suck one into itself while, at the same time, the sculpture is within the bubble is retiring away.

While DeMaria and Koons use costly, industrial products, Butter employs inexpensive, do-it-yourself materials. His work suggests the hobbyist's basement or the moonlighter's garage workshop. His work is handcrafted, but in the suburban rather than rural sense: homemade boats, custom-designed cars, tool sheds. Yet this class of objects appears through inference rather than reference, from materials and techniques more than the forms themselves. His mass-produced materials are put to wholly personal uses.

Butter's sculptures tend to be organized in dualities: skeleton/skin, outside/inside, fiberglass/plywood, opacity / transluency. They also tend to have two distinct sides, from one side the other is invisible. To move around the piece is to be surprised. Once the piece has been circumnavigated, the relation .of side to side becomes apparent, but each retains its autonomy. Apart from the major vertical thrust of his floor pieces-they loom up from the ground like splitting pods-no single part reaches out to grab space. The work keeps to itself. Butter is interested in the negative space of internal volume but not in the eccentric negative space that would be produced by limbs or extensions. If he worked with human forms he would probably concentrate on the torso. And yet, these pieces are about lightness and light - lightness of touch, of gesture, of technique. They do not defy gravity, but they are not excessively troubled by it. One person could probably move them, just as one person made them.

But are they too light? Do they betray a nostalgia for easier times when the typical American male asked for nothing more than an eternal weekend of leisurely bricolage? The underlying confidence and evident charm of these works puts us at our ease. They suggest a solid life without sharp edges, an imagination on a human scale. The reductivist lebensraum of De Maria and the cynical paucity of Koons say more about the present state of things than Butter's inventive constructs, but then again, diagnosis is cheap, cures altogether too rare. -Meyer Raphael Rubinstein, “Sites and Sights: Considerations on Walter De Maria, Jeff Koons, and Tom Butter.” Arts, March 1987, p. 20–21.

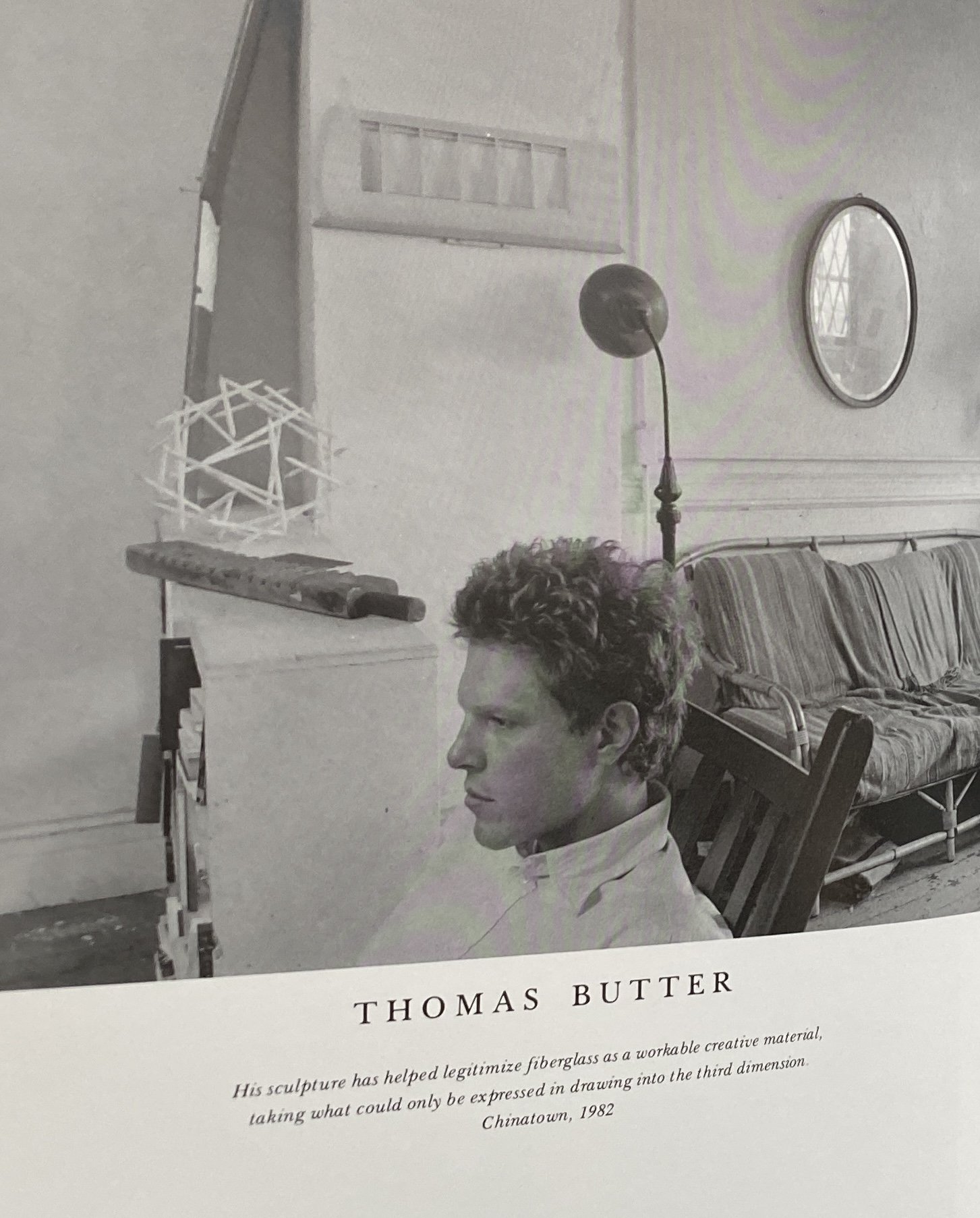

Harvey Stein, Artists Observed, (Harry N Abrams: 1986) p. 36-7

W.H./M.M.D., 1983, fiberglass and resin, 16’ high (4.87 meters), Hammarskjold Plaza Sculpture Garden, Second avenue at 47th St., New York City (photo: Peter Bellamy)

Cryptically titled W.H./M.M.D., this three-part sculpture is Tom Butter’s second large scale, public, outdoor work, and his first in a wholly urban setting (the other was installed last summer in the sylvan pool in Central Park at 100th Street). Made of polyester resin, fiberglass cloth, and steel, it is a narrow organic structure in which irregular translucent forms play contrapuntally with the rectilinear environment of steel and glass. Two opposing vertical elements -one melon-colored, the other gray green - appear to be rising from a dark gray base of curving, inflated forms.

W.H./M.M.D., 1983, fiberglass and resin, 11 x 12 x 8.5 feet (3.35 x 3.65 x 2.59 meters), Hammarskjold Plaza Sculpture Garden, Second avenue at 47th St., New York City (photo: courtesy of the artist)

The first element bulges at its middle while the second bears a trumpetlike flare at its top. One is ungainly, the other is elegant; one warm hued, the other cool. Narrow seaming inflects the flared column, while the other is broad in striation. The irregular ground forms, often punched and riddled with dents, look like some heap of rubbish, yet enclose the vertical members with encircling, even enfolding gestures. Below them lies a dark gray wooden base, as if in mimicry of a sculpture pedestal.

For Immediate Release, Tom Butter at Hammarskjold Plaza Sculpture Garden, June through September 1983

In this work Butter seems to mimic many terms conventional to public art. The sculpture is places smack in the middle of the plaza, in perfect ‘pedestal position’ exactly where you’d expect a Henry Moore, in fact. Moreover, although it has a base, the conventional metaphor for meaning, it is without direct content, modeled on the monument, the sculpture subverts its connotations. Butter’s strategy consists in placing familiar elements in unfamiliar configurations, adding ambiguity to a field known for dependency on publicly recognizable forms. the organic shapes, curved and irregular, work against the rigid grid of the skyscrapers, playing unfixity against fixity of meaning and with it, unfixity of function. The work’s why and wherefore remain unknowable: these are fugitive forms, eluding precise definition; they are endlessly evocative, but evade the closure of meaning. In the appear made on the viewer to reject conventional responses, this allusive and highly equivocal work has important public power.

Kate Linker, Artforum, November 1983, p. 76

One of the more successful outdoor sculptures this summer season. is Tom Butter’s “W.H.-M.M.D.”, at the Hammarskjold Plaza Sculpture Garden, 866 Second Avenue, through September. The scale of the work is right, and the interaction between the organic and architectural shapes and vertical ahd horizontal movements make the work a forceful point of orientation for the trees and buildings around it.

The polyester resin, fiberglass cloth and steel sculpture consists primarily of two vertical forms, each around 12 feet high. One is a thin, fluted, grey-green column flaring at the top. ·Alongside it is something of a cross between an over-ripe tropical plant and a tube swollen in the middle. While the-columnar form reaches upwards, like an offering to the architecture and sky, the strawberry red tube-like form squeezes the movement laterally, turning the sculpture towards the horizontals of the streets.

Reinforcing the tension between manmade and organic growth and decay, are perhaps 50 smaller objects - something of a cross between the peels of a monstrous fruit and scraps of industrial waste - squirming about at the foot of the work. What are these forms? What is happening· -here? The tension is heightened by the light. When the sun is behind the viewer, the sculpture seems solid, expansive, secure. When the sculpture is between the viewer and the sun, the fiberglass becomes translucent. _Now, however, the sculpture seems fragile, as if an angry pin would be enough to turn the sculpture into a pile of waste.

-Michael Brenson, In the Arts: Critics Choice, The New York Times, August 21, 1983

Peter Bellamy, The Artist Project, Portraits of the Real Art World / New York Artists, 1981-1991, (IN Publishing: 1991), p. 162

P.G., 1982, fiberglass and resin, Sylvan Pool, Central Park at 100th Street, New York City

Press release, Sculpture in the Pool st 100th St., curated by Gilbert Coker & Horace Brockington

Fleece (1987), polyester resin, pigment, steel mesh, 73 x 23 x 45 inches (1.8 x .5 x 1.09 m)

Fleece (2000’s), polyester resin, pigment, steel mesh 73 x 23 x 45 inches (1.8 x .5 x 1.09 m)

Stroll in the Woods (2000), fiberglass resin, pigment, wood and steel, 37 x 51 x 24 inches (93 x 120 x 60 cm)

detail, Stroll in the Woods (2000), fiberglass resin, pigment, wood and steel

Fits and Starts (2000), steel, fiberglass, pigmented resin, plexiglass, 28 x 31 x 13 inches (71 x 78 x 33 cm)

detail, Fits and Starts (2000), steel, fiberglass, pigmented resin, plexiglass, 28 x 31 x 13 inches (71 x 78 x 33 cm)

Vector (1999), steel, fiberglass, pigmented resin, and wood, 25 x 23 x 20 inches (65.3 x 58.4 x 50.8 cm)

detail, Vector (1999), steel, fiberglass, pigmented resin, and wood, 25 x 23 x 20 inches (65.3 x 58.4 x 50.8 cm)

Discs and Hoops (1999), steel, fiberglass, pigmented resin, and plexiglass, 30 x 28 x 14 inches (76.2 x 71.1 x 35.5 cm)

detail, Discs and Hoops (1999), steel, fiberglass, pigmented resin, and plexiglass, 30 x 28 x 14 inches (76.2 x 71.1 x 35.5 cm)

BOAT SEA, fiberglass and steel with wood, freestanding sculpture: 6 feet high, three feet wide, 2 feet deep

BOAT SEA detail

FOOTBRIDGE, polyester resin on steel with old shoe, freestanding sculpture: 8 feet long, 3 feet high, two feet wide

DRYDOCK, freestanding sculpture: 5 feet high, 4 feet in diameter

GROVE (1995), glass, wood, graphite, freestanding sculpture: 56 inches high, 22 inches wide, 26 inches deep